Sun Cross

Sun Cross

Also known as Ringed Cross, Cross in the Circle.

Overview

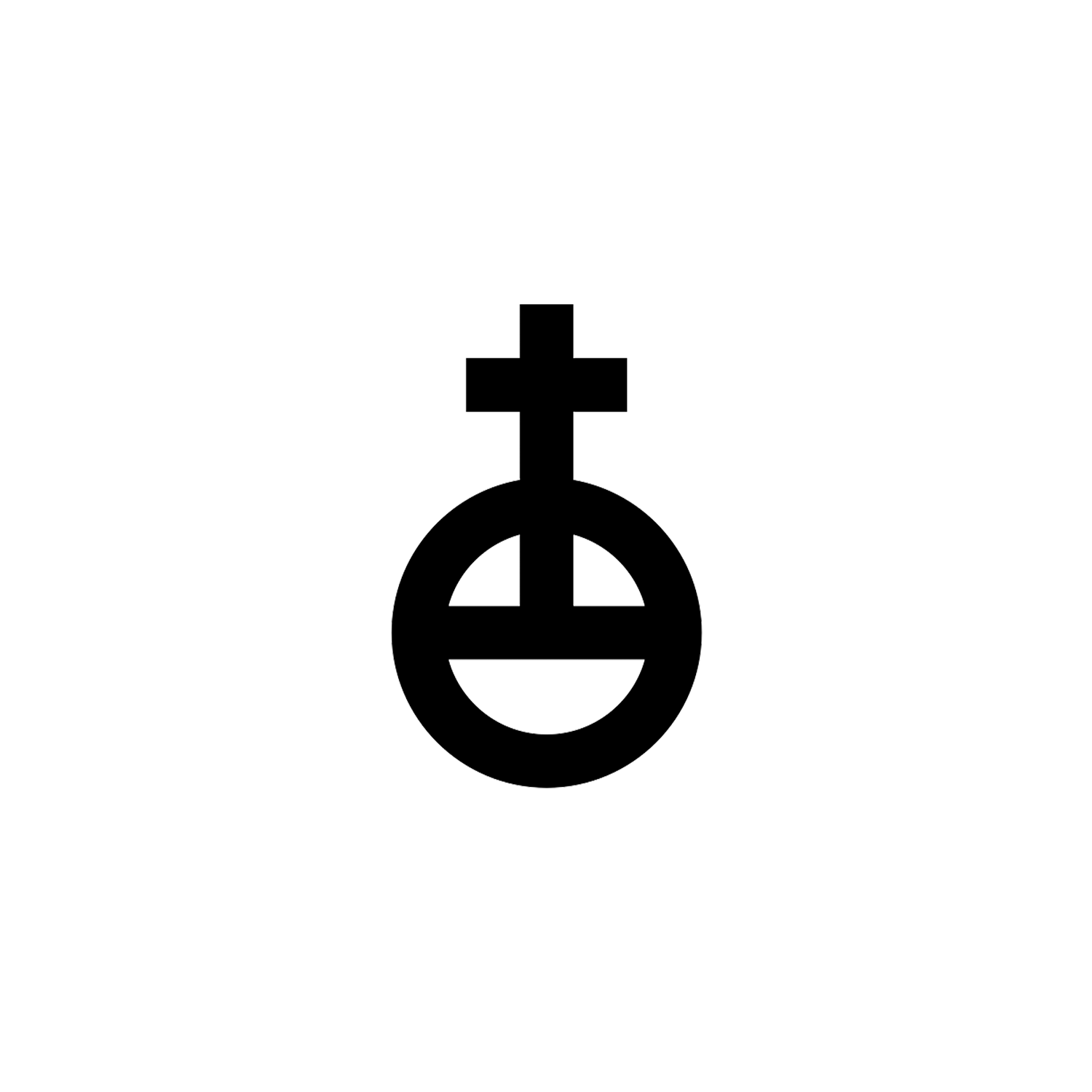

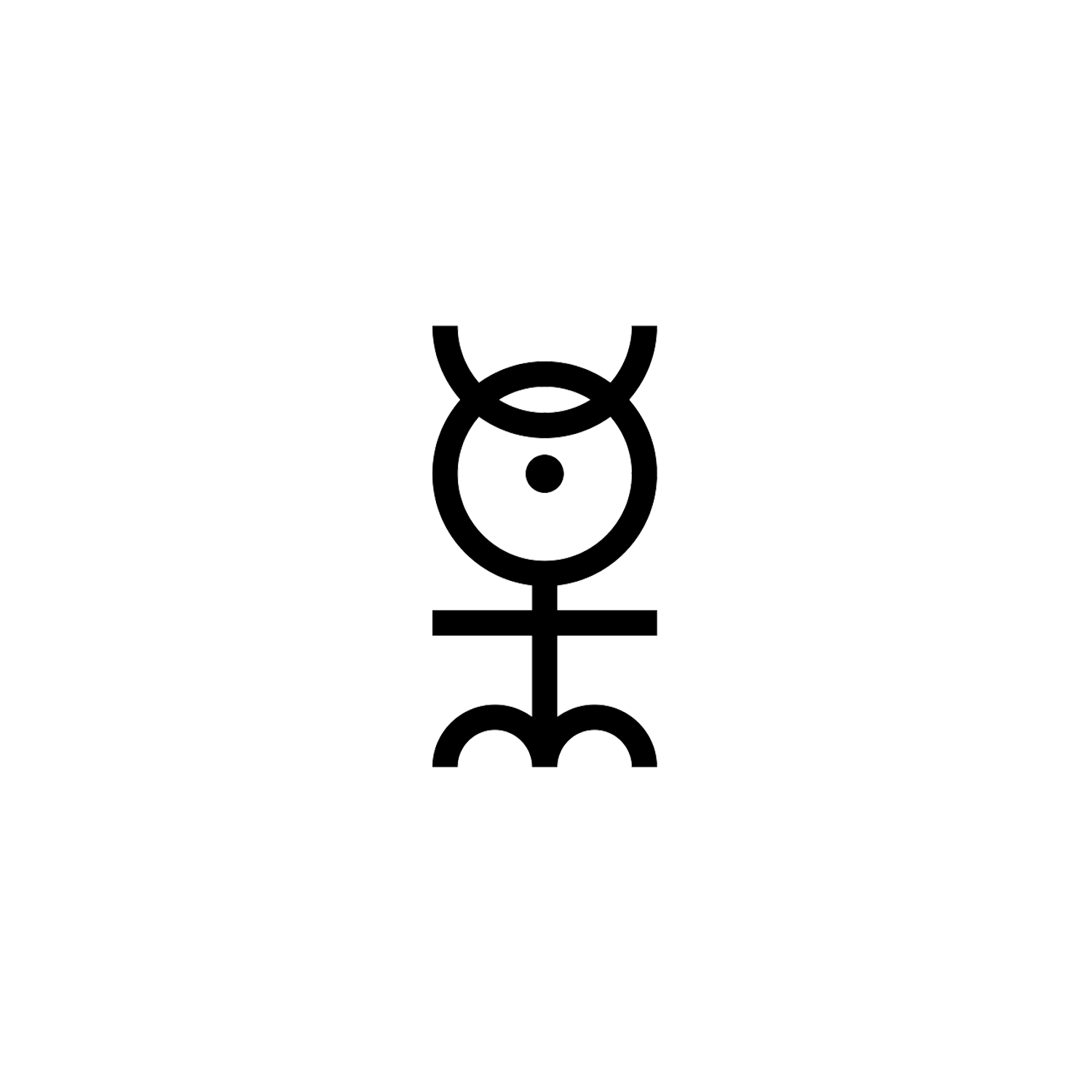

A sun cross, solar cross, or wheel cross is a solar symbol consisting of an equilateral cross inside a circle.

The design is frequently found in the symbolism of prehistoric cultures, particularly during the Neolithic to Bronze Age periods of European prehistory.

The symbol’s ubiquity and apparent importance in prehistoric religion have given rise to its interpretation as a solar symbol, whence the modern English term “sun cross” (a calque of German: Sonnenkreuz). The symbol means village in Ancient Egyptian (Gardiner symbol O49).

When referred to as the Cross in the Circle, it usually is of the alchemical meaning of it—Verdigris.

The same symbol is in use as a modern astronomical symbol representing the Earth rather than the Sun. In pharmacy, a sun cross symbol represents various/miscellaneous medications.

Origin and Meaning

The interpretation of the simple equilateral cross as a solar symbol in Bronze Age religion was widespread in 19th-century scholarship. The cross-in-a-circle was interpreted as a solar symbol derived from the interpretation of the disc of the Sun as the wheel of the chariot of the Sun god.[1]

In the prehistoric religion of Bronze Age Europe, crosses in circles appear frequently on artifacts identified as cult items, for example the “miniature standard” with an amber inlay that shows a cross shape when held against the light, dating to the Nordic Bronze Age, held at the National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen.[2]

The Bronze Age symbol has also been connected with the four-spoked chariot wheel, which is attested in Bronze Age Scandinavia, Central Europe and Greece (compare the Linear B ideogram 243 “wheel” 𐃏). In the context of a culture that celebrated the sun chariot, it may thus have had a “solar” connotation (compare the Trundholm sun chariot).

The chariot has been interpreted as a possible Bronze Age predecessor to Skinfaxi,[3] the horse that pulled Dagr, the personification of day, across the sky.

In the Celtic Pantheon the sky god Taranis is typically depicted with the attribute of a spoked wheel. In Greek mythology, the solar deity Helios was said to wear a radiant crown as his horse-drawn chariot raced across the sky, bringing daylight.

The Sun Cross has a relation to medicine wheels, which follow a similar pattern of a central circle or cluster of stones, surrounded by an outer ring of stones, along with “spokes” (lines of rocks) radiating from the center out to the surrounding ring. Often, but not always, the spokes may be aligned to the cardinal directions (East, South, West, and North). In other cases, some stones may be aligned with astronomical phenomena. These stone structures may be called “medicine wheels” by the Indigenous nation which built them, or by more specific names in that nation’s language.

Physical medicine wheels made of stone have been constructed by a number of different Indigenous cultures in North America, notably many of the Plains nations. The structures are associated with Native American and Indigenous Canadian religious ceremonies.

The modern Medicine Wheel symbol, which was invented as a teaching tool around 1972 by Charles Storm, aka Arthur C. Storm, writing under the name Hyemeyohsts Storm, in his book Seven Arrows and further expanded upon in his book Lightningbolt[4][5]. It has since been used by various people to symbolize a variety of concepts, some based on Native American religions, others newly invented and of more New Age orientation.

The English term “Sun-Cross”, on the other hand, is comparatively recent, apparently loaned from German Sonnenkreuz and used in the 1955 translation of Rudolf Koch’s Book of Signs (“The Sun-Cross or Cross of Wotan”, p. 94).

The German term Sonnenkreuz was used in 19th-century scholarly literature of any cross symbol interpreted as a solar symbol, an equilateral cross either with or without a circle, or an oblique cross (Saint Andrew’s cross).

Sonnenkreuz was used of the flag design of the Paneuropean Union in the 1920s.[6]

In the 1930s, a version of the symbol with broken arms (resembling a curved swastika, illustrated below) was popular as a link between Christianity and Germanic paganism in the völkisch German Faith Movement.[7]

Alchemy and the Cross in the Circle

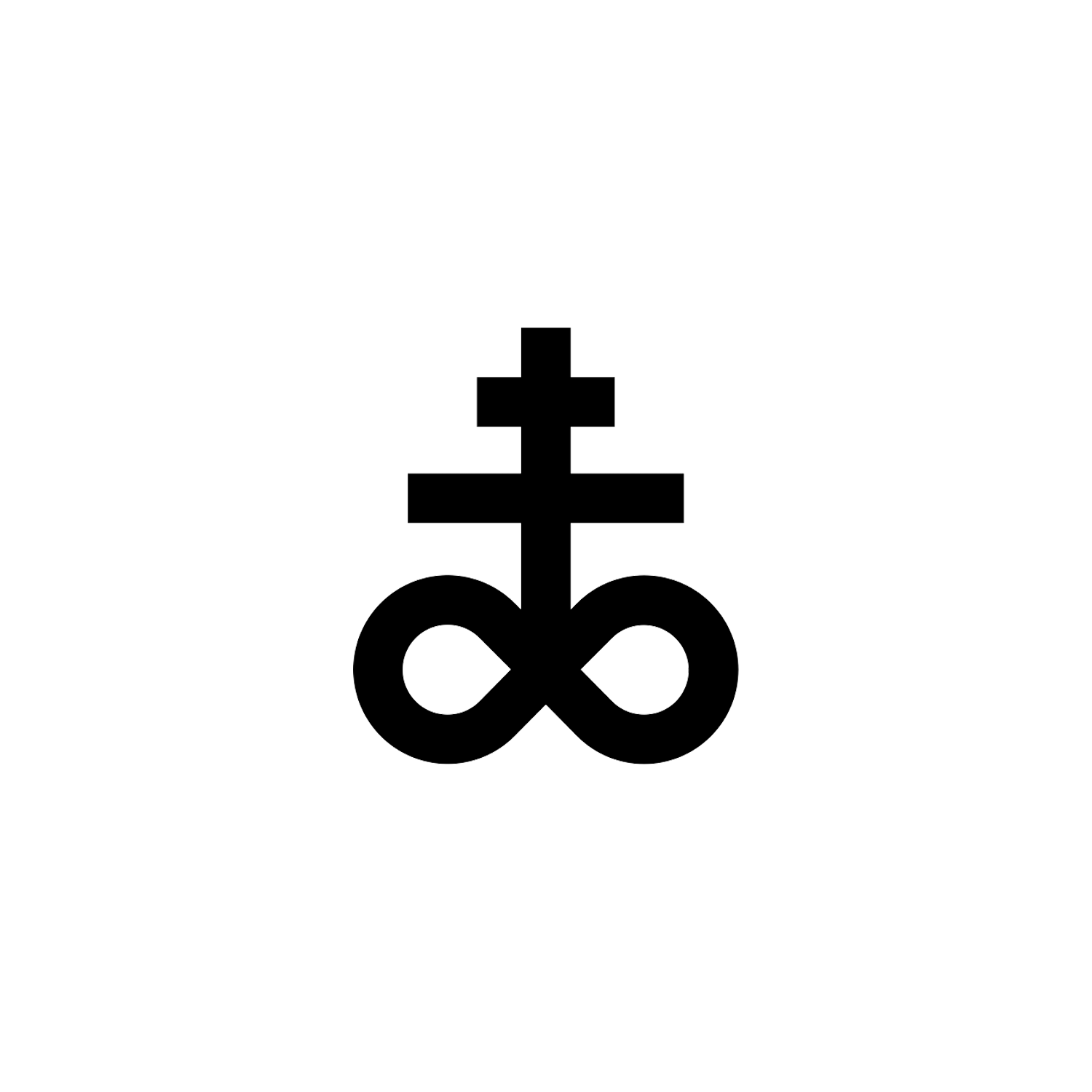

The Sun Cross, referred to as the Cross in the Circle in Alchemy is used as the symbol for Verdigris.

The name verdigris comes from the Middle English vertegrez, from the Old French verte grez. According to one view, it comes from vert d’aigre,[8] “green [made by action] of vinegar”.

Verdigris /ˈvɜːrdɪɡriː(s)/[9] is a common name for any of a variety of somewhat poisonous[10][11][12][13] copper salts of acetic acid, which range in colour from green to a bluish-green depending on their chemical composition.[14] Once used as a medicine[15][16] and pharmaceutical preparation,[17] [18] Verdigris occurs naturally, creating a patina on copper, bronze, and brass, and is the main component of a historic green pigment used for artistic purposes from antiquity until the late 20th century, including in easel painting, polychromatic sculptures, and illumination of maps.[19] [20]

However, due to its instability, its popularity declined as other green pigments became readily available.[21] The instability of its appearance stems from its hydration level and basicity, which changes as the pigment interacts with other materials over time. This is evident in the Statue of Liberty, which is a symbol in and of itself (actually there are multiple Statues of Liberty, as explained in the article).

With the slight departure from the symbol itself and into what it actually symbolizes in Alchemy we can understand potential underlying definition and uses of the Verdigris, which Cennino Cennini, in his 15th century text Il Libro dell’Arte, describes as being ‘manufactured by alchemy, from copper and vinegar’.[22]

This is the most common way to artifically produce the copper salts, it is also how the green pigment described earlier was made, an unstable paint which was used by Vermeer (albeit infrequently) and Raphael for the green coat of Saint John in the Mond Crucifixion.[23]

In the Hermetic context, the Sun Cross is considered synonymous with the Unicursal Hexagram by some.

Sun Cross in Christianity

The ringed cross is a class of Christian cross symbols featuring a ring or nimbus. The concept exists in many variants and dates to early in the history of Christianity. One variant, the cruciform halo, is a special type of halo placed behind the head of Jesus in Christian art. Other common variants include the Celtic cross, used in the stone high crosses of Ireland and Britain; some forms of the Coptic cross; and ringed crosses from western France and Galicia.

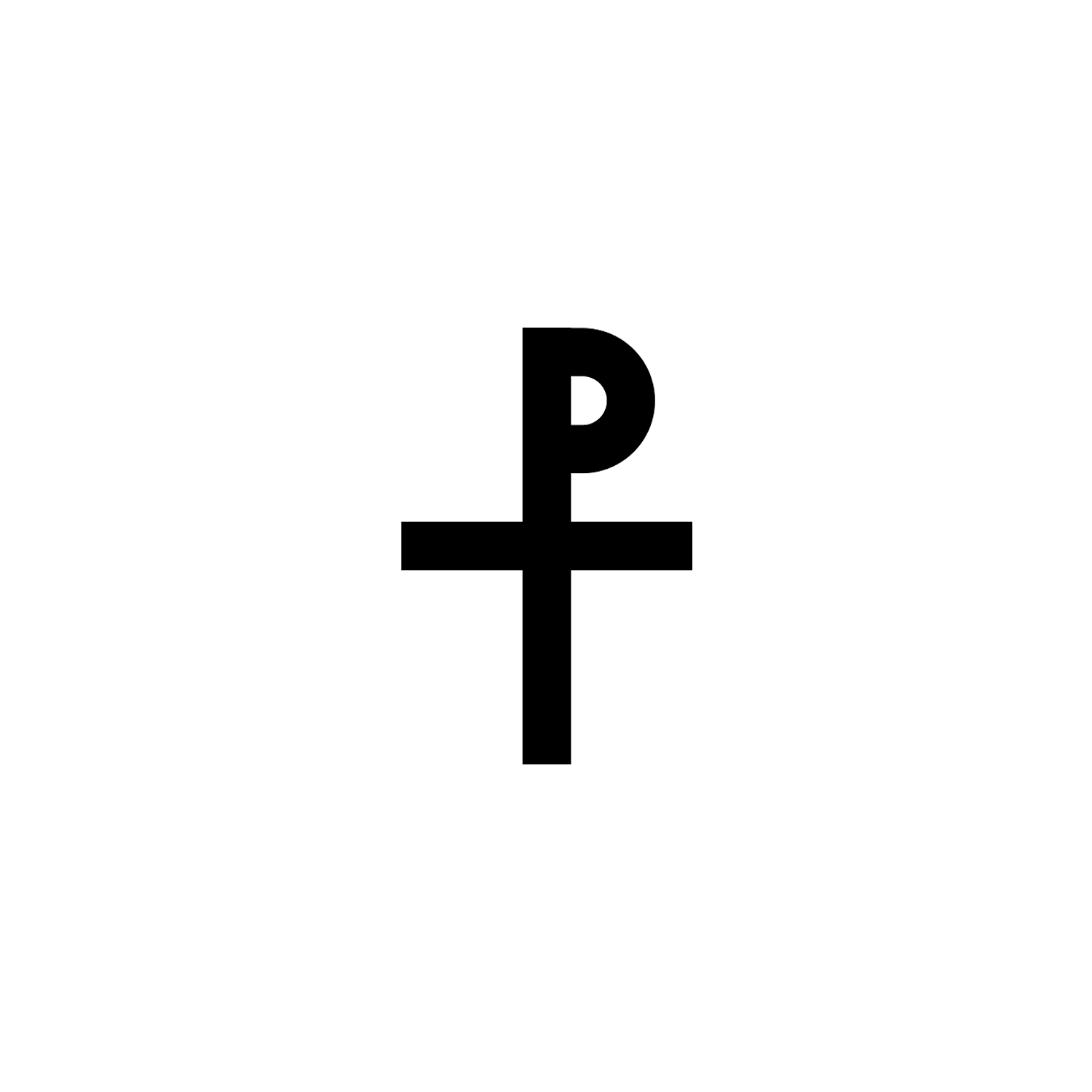

The nimbus or ringed shape was appended to the Christian cross and other symbols relatively early. In these contexts it apparently derived from the earlier Roman garland of victory. The Chi Rho-in-circle motif was widespread in the Roman Empire by the late 4th century, and garlanded and ringed crosses were popular in imperial Ravenna by the 5th century, influencing the later versions.[24] The cruciform halo or cross halo, a halo incorporating a cross, emerged as a distinctive type of halo painted behind the head of members of the Holy Trinity, especially Jesus, and occasionally others.[25]

In other cases, the combination of cross and nimbus symbolized the presence of Christ throughout the cosmos, with the nimbus representing the celestial sphere. Notable early examples include the cosmological ringed cross in the 5th-century Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, and the 6th-century Crux Gemmata in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe.[26]

Earth Symbol

A variety of symbols or iconographic conventions are used to represent Earth, whether in the sense of planet Earth, or the inhabited world, or as a classical element. A circle representing the round world, with the rivers of Garden of Eden separating the four corners of the world, or rotated 45° to suggest the four continents, remains a common pictographic convention to express the notion of “worldwide”.

The current astronomical symbol for the planet is a circle with an intersecting cross, An equilateral cross enclosed in a circle.[27] Although the International Astronomical Union (IAU) now discourages the use of planetary symbols, this is an exception, being used in abbreviations such as M🜨 for Earth mass which also incorporates the Cross in the Circle.[28]

The globus cruciger (♁) is the globe surmounted by a Christian cross, held by Byzantine Emperors on the one hand to represent the Christian ecumene, on the other hand the akakia represented the mortal nature of all men.

In the medieval period, the known world was also represented by the T-and-O figure, representing an extremely simplified world map of the three classical continents of the Old World, viz. Asia, Europe and Africa in various orientations:

Conclusion

The Sun Cross, an ancient symbol predating the Bronze Age, consists of a circle intersected by a cross within.

Originally representing the wheel and its societal significance, it later evolved and had other meanings attributed to it.

Widespread across the globe, the Sun Cross was initially depicted on cave walls and featured in early written records. Its meaning has transitioned over time, shifting from power to an earthly connotation. Alchemists utilized it to represent copper salts, linked to the Earth.

Astrologers also adopted the symbol to signify the Earth. Within Christian iconography, it signifies power, harking back to its original usage. Additionally, Christians employ it to represent halos, symbolizing the superiority of saints and angels over mortals.

[1] Martin Persson Nilsson (1950). The Minoan–Mycenaean Religion and its Survival in Greek Religion. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. p. 421. there is a wide-spread opinion that the equal-limbed cross is another symbol of the sun. It was, for example, a favorite theory of the late Professor Montelius, and has been embraced by many other archaeologists; its wide acceptance is due to an interest in finding a pre-Christian origin of the symbol of Christianity. The disc of the sun was regarded as a wheel; hence the myth that the sun-god drives in a chariot across the heavens.

[2] Enter at the Nebra sky disk exhibition site (landesmuseum-fuer-vorgeschichte-halle.de)

[3] Lindow, John. (2001) Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs, page 272. Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-515382-0.

[4] Shaw, Christopher (August 1995). "A Theft of Spirit?". New Age Journal. pp. 84–92. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

[5] Jenkins, Philip (21 September 2004). Dream Catchers: How Mainstream America Discovered Native Spirituality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195347654. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018.

[6] Richard Nicolaus Graf von Coudenhove-Kalergi, Kampf um Paneuropa aus dem 1. Jahrgang von Paneuropa, Paneuropa Verlag, 1925, p. 36.

[7] Waldemar Müller-Eberhart, Kopf und herz des Weltkrieges: General Ludendorffs Wertung als Deutscher, Georg Kummer, 1935, p. 244.

[8] Dauthenay, Henri (1905). Répertoire de couleurs pour aider à la détermination des couleurs des fleurs, des feuillages et des fruits. Vol. 2. Paris: Librairie horticole. p. 240. RC2.

[9] "Its pronunciation in English is still unsettled" (Fowler's Dictionary of Modern English Usage (4 ed.) edited by: Jeremy Butterfield). The pronunciation /-ɡriːs/ is the first one given by Merriam-Webster's dictionary, but /-ɡriː/ is first in the Oxford Dictionary of English (3 ed.) (2015).

[10] "Verdigris". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

[11] Karmakar, Rabindra N. (2015). Forensic medicine and toxicology: theory, oral & practical. Academic Publishers.

[12] Anant, Jagdish Kumar, S. R. Inchulkar, and Sangeeta Bhagat (2018). "An overview of copper toxicity relevance to public health." EJPMR 5, no. 11 : 236.

[13] "Poisoning by Verdigris". The Lancet. 39 (1013): 663–664. January 1843. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)76992-4. ISSN 0140-6736.

[14] H. Kühn, Verdigris and Copper Resinate, in Artists' Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2: A. Roy (Ed.) Oxford University Press 1993, p. 131 – 158

[15] "Medical Uses of Copper in Antiquity". Copper Development Association.

[16] Paris, John Ayrton (1831). Pharmacologia. New York: W. E. Dean. The rust of the spear of Telephus, mentioned in Homer as a cure for the wounds which that weapon inflicted, was probably Verdegris, and led to the discovery of its use as a surgical application

[17] Benhamou, Reed (1984). "Verdigris and the Entrepreneuse". Technology and Culture. 25 (2): 171–181. doi:10.2307/3104711. ISSN 0040-165X. JSTOR 3104711. S2CID 112614238.

[18] De la Roja, José Manuel; San Andrés, Margarita; Cubino, Natalia Sancho; Santos-Gómez, Sonia (2007). "Variations in the colorimetric characteristics of verdigris pictorial films depending on the process used to produce the pigment and the type of binding agent used in applying it". Color Research & Application. 32 (5): 414. doi:10.1002/col.20311. ISSN 0361-2317.

[19] De la Roja, José Manuel; San Andrés, Margarita; Cubino, Natalia Sancho; Santos-Gómez, Sonia (2007). "Variations in the colorimetric characteristics of verdigris pictorial films depending on the process used to produce the pigment and the type of binding agent used in applying it". Color Research & Application. 32 (5): 414. doi:10.1002/col.20311. ISSN 0361-2317.

[20] Verdigris, ColourLex

[21] Benhamou, Reed (1984). "Verdigris and the Entrepreneuse". Technology and Culture. 25 (2): 171–181. doi:10.2307/3104711. ISSN 0040-165X. JSTOR 3104711. S2CID 112614238.

[22] Cennini, Cennino, active 15th century. "Il libro dell'arte". archive.org

[23] Bette, Sebastian; Kremer, Reinhard K.; Eggert, Gerhard; Tang, Chiu C.; Dinnebier, Robert E. (2017). "On verdigris, part I: synthesis, crystal structure solution and characterisation of the 1–2–0 phase (Cu3(CH3COO)2(OH)4)". Dalton Transactions. 46 (43): 14847–14858. doi:10.1039/c7dt03288a. ISSN 1477-9226. PMID 29043336.

[24] Herren, Michael W.; Brown, Shirley Ann (2002). Christ in Celtic Christianity: Britain and Ireland from the Fifth to the Tenth Century. Boydell Press. pp. 192–193. ISBN 0851158897.

[25] Sill, Gertrude Grace (2011). A Handbook of Symbols in Christian Art. Simon & Schuster. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-1439123843.

[26] Herren, Michael W.; Brown, Shirley Ann (2002). Christ in Celtic Christianity: Britain and Ireland from the Fifth to the Tenth Century. Boydell Press. pp. 199–200. ISBN 0851158897.

[27] "Solar System Symbols". NASA. 18 March 2019.

[28] The IAU Style Manual (PDF). 1989. p. 27.

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.