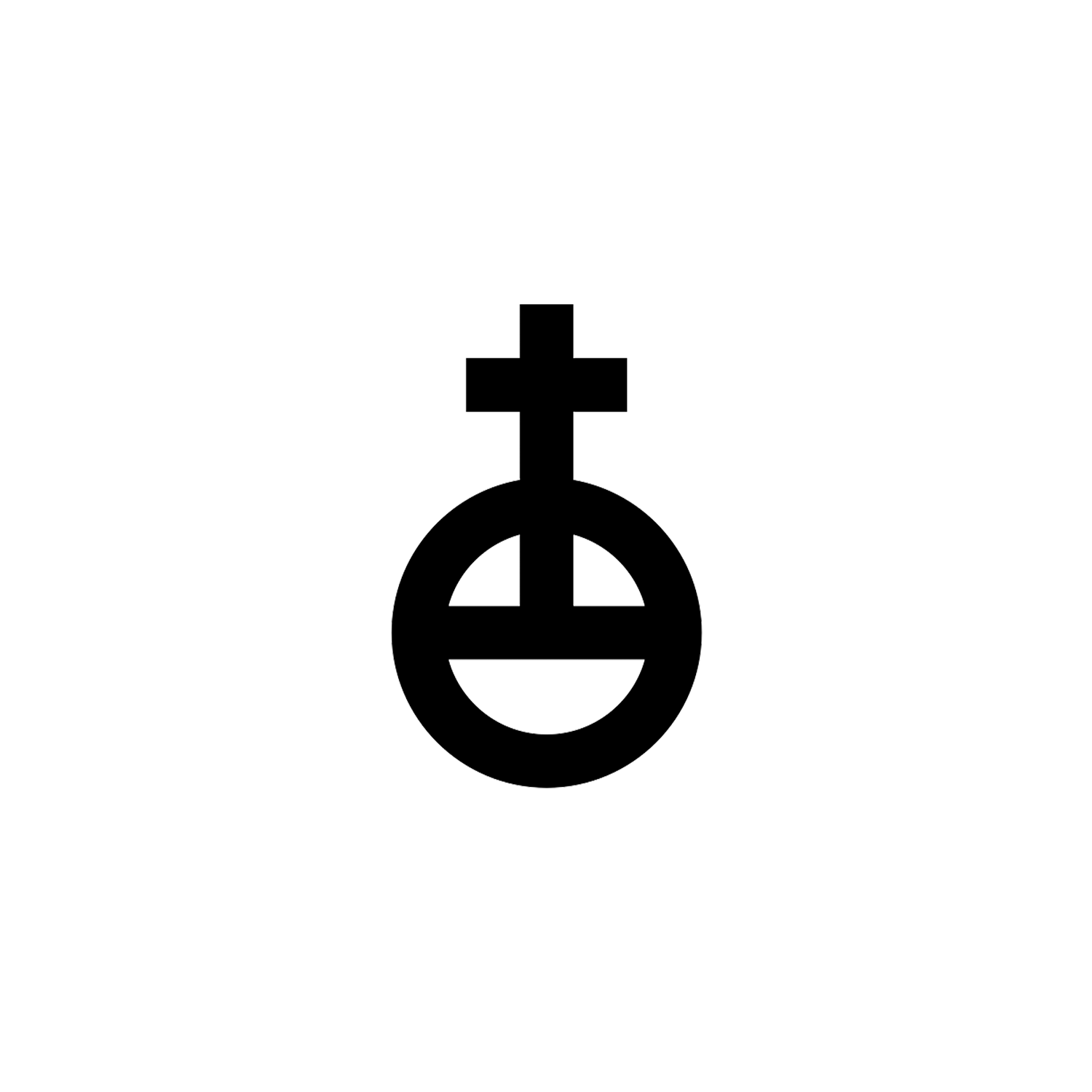

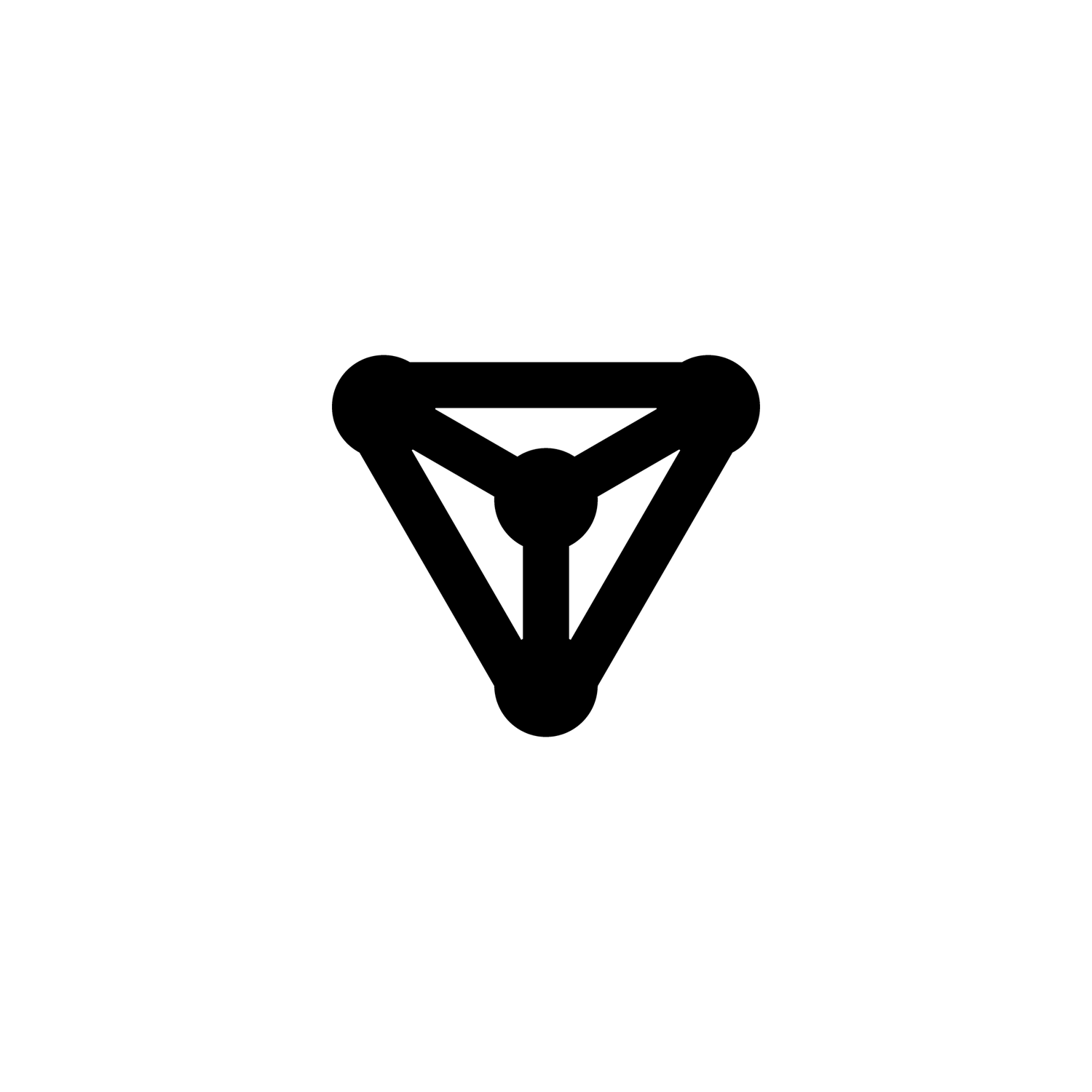

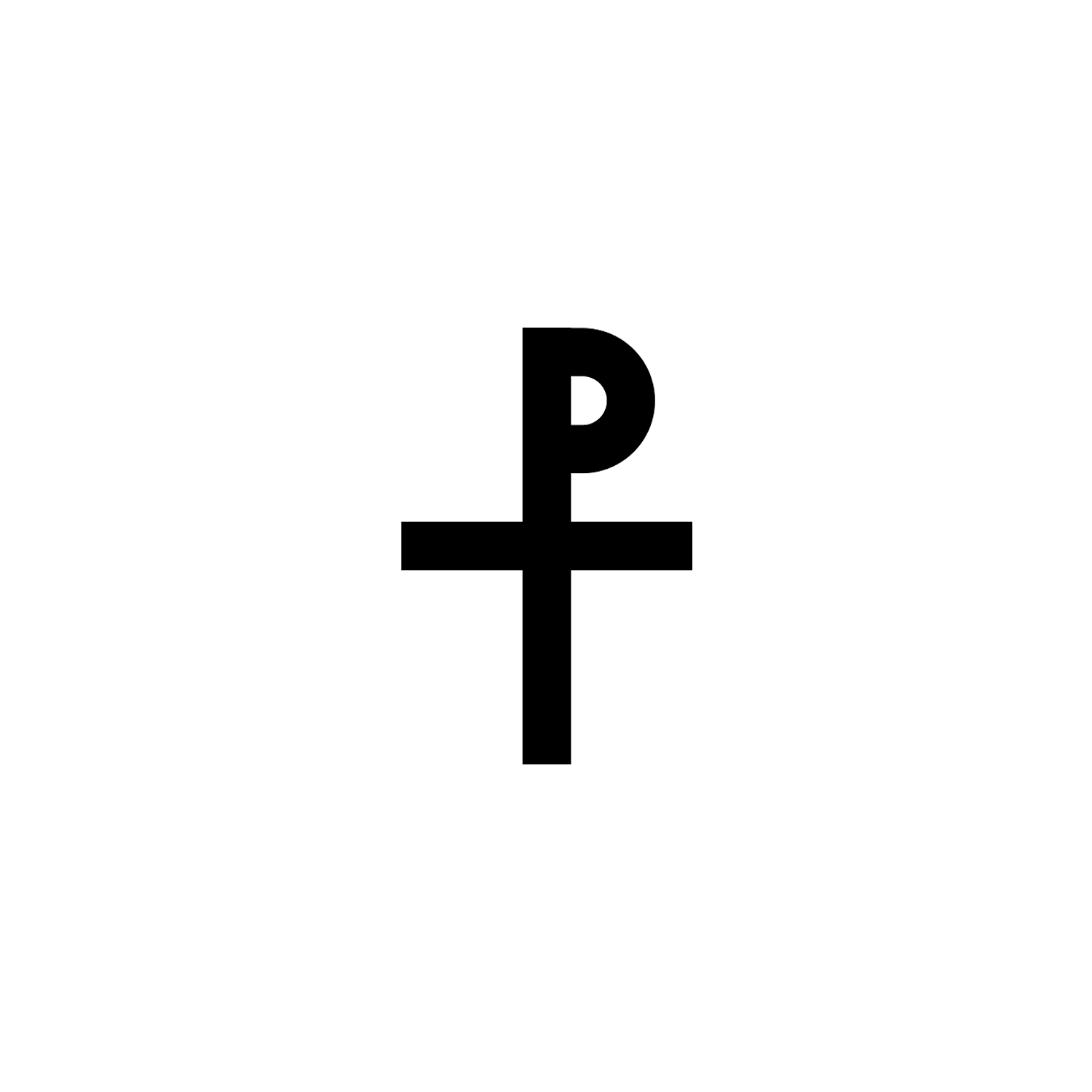

Staurogram

Staurogram

Also referred to as monogrammatic cross or tau-rho.

Overview

The staurogram (⳨), also monogrammatic cross or tau-rho,[1] is a ligature composed of a superposition of the Greek letters tau (Τ) and rho (Ρ).

Origin and Meaning

The symbol is of pre-Christian origin. It is found on copper coins minted by Herod I in 37 BC, interpreted as a tr ligature representing trikhalkon indicating the coin value.[2]

The staurogram was first used to abbreviate stauros (σταυρός), the Greek word for cross, in very early New Testament manuscripts such as 𝔓66, 𝔓45 and 𝔓75, almost like a nomen sacrum, and may visually have represented Jesus on the cross.[3]

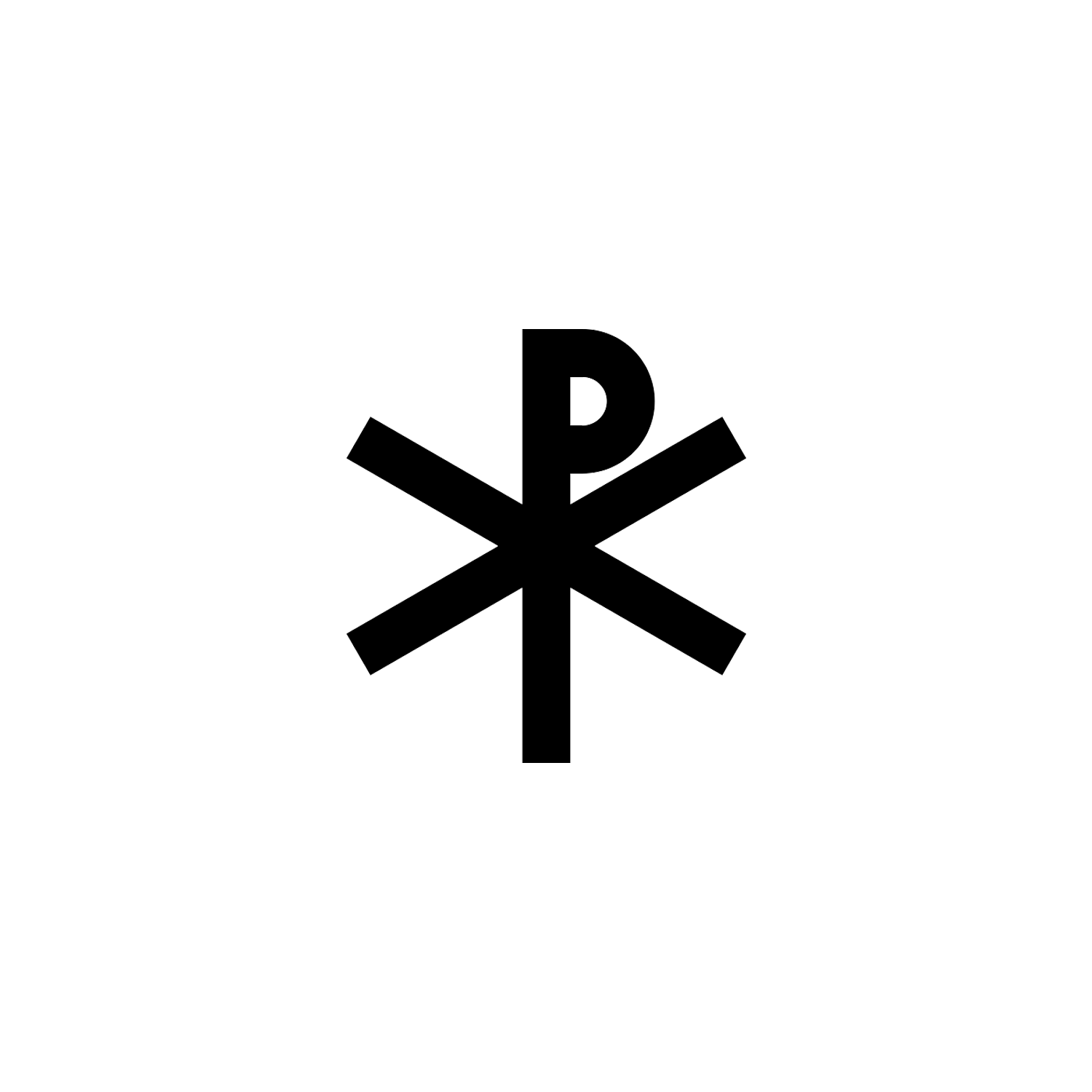

The Tau-Rho as a Christian symbol outside its function as nomen sacrum in biblical manuscripts appears from c. the 4th century, used as a monogramma Christi (Christogram, a monogram or combination of letters that forms an abbreviation for the name of Jesus Christ, traditionally used as a religious symbol within the Christian Church) alongside the Chi-Rho and other variants, spreading to Western Europe in the 5th and 6th centuries.[4]

Ephrem the Syrian (4th century) discusses a Christian symbol, apparently combining the Tau-Rho with Alpha and Omega placed under the left and right horizontal arms of the Tau.

Ephrem says that the Tau represents the cross of Jesus (prefigured by the outstretched hands of Moses in Exodus 17:11), the Alpha and Omega signify that the crucified Christ is “the beginning and end“, and the Rho, finally, signifies “Help” (βοήθια [sic]; classical spelling: βοήθεια), because of the numerological value of the Greek word being 100, represented by Rho as a Greek numeral.[5]

The two letters tau and rho can be found separately (not in ligature) as symbols already on early Christian ossuaries.[6]

Tertullian (Contra Marcionem 3.22) explains the Tau as a symbol of salvation by identification with the sign which in Ezekiel 9:4 was marked on the forehead of the saved ones.[3] In antiquity, the cross, i.e. the instrument of Christ’s crucifixion (crux, stauros), was taken to be T-shaped.

The rho by itself can refer to Christ as Messiah because Abraham, taken as symbol of the Messiah, generated Isaac according to a promise made by God when he was one hundred years old, and 100 is the value of rho.[6]

Conclusion

The tau-rho staurogram is one of several christograms, or monogram-like devices, used by ancient Christians to refer to Jesus. The origin of the symbol, however, is of pre-Christian origin and was used on ancient coins, where it represented the value of the coin.

The symbol is very similar to the Chi-Rho, also known as Labarum.

In time christograms came to be used not only in texts but as free-standing symbols of Christ or Christian faith, for example on liturgical vestments and church utensils. This was probably also true of the staurogram, tau-rho; where it would represent simply an independent symbol of Christ or Christian faith.

But the earliest use of the tau-rho was as a visual reference to Jesus’ crucifixion. As such, it is the earliest surviving depiction of Jesus’ crucifixion.

[1] The term staurogram in this sense is of relatively late coinage (1960s); "monogrammatic cross" is in use in the later 19th century.

[2] F. W. Madden, History of Jewish Coinage (1864), 83–85.

[3] Hurtado, Larry (2006). "The Staurogram in Early Christian Manuscripts: the earliest visual reference to the crucified Jesus?". In Kraus, Thomas (ed.). New Testament Manuscripts. Leiden: Brill. pp. 207–26. hdl:1842/1204. ISBN 978-90-04-14945-8.

[4] Redknap, Mark (1991). The Christian Celts: treasures of late Celtic Wales. Cardiff: National Museum of Wales. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7200-0354-3.

[5] Hurtado (2006), citing F. J. Dölger, Sol Salutis (1920), p. 61 (note 2). Ephraem in sanctam Parasceven, Ephraem Syri opera omnia quae extant graece — syriace — latine Tom. III Romae 1746, p. 477.

[6] Bagatti, Bellarmino, "The Church from the Circumcision: History and Archaeology of the Judaeo-Christians", Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Collectio Minor n. 2, p. 158. Jerusalem (1984).

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.