Cult of Mithras

Cult of Mithras

Also known as Mithraism and the Mithraic Mysteries.

Overview

Mithraism, also known as the Mithraic mysteries or the Cult of Mithras, was a Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras.

Although inspired by Iranian worship of the Zoroastrian divinity (yazata) Mithra, the Roman Mithras was linked to a new and distinctive imagery, and the level of continuity between Persian and Greco-Roman practice remains debatable.[1] The mysteries were popular among the Imperial Roman army from the 1st to the 4th century CE.[2]

Mithra is the Iranian god of the sun, justice, contract, and war in pre-Zoroastrian Iran.

Known as Mithras in the Roman Empire during the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, this deity was honoured as the patron of loyalty to the emperor. After the acceptance of Christianity by the emperor Constantine in the early 4th century, Mithraism rapidly declined.

Origin and Meaning

Mithras has his roots in ancient Persia, where he was known as Mithra, a god associated with the sun and light. The Romans adopted and adapted Mithras into their own religious pantheon, creating the secretive Cult of Mithras, which was particularly popular among Roman soldiers, who admired his association with bravery, strength, and the sun. The idea of the blood sacrifice of the bull feeding the earth also played a role in the minds of the soldiers shedding their own blood on the battlefields.

The name Mithras (Latin, equivalent to Greek Μίθρας[3]) is a form of Mithra, the name of an old, pre-Zoroastrian, and, later on, Zoroastrian, god[4][5] – a relationship understood by Mithraic scholars since the days of Franz Cumont.[6] An early example of the Greek form of the name is in a 4th century BCE work by Xenophon, the Cyropaedia, which is a biography of the Persian king Cyrus the Great.[7]

The exact form of a Latin or classical Greek word varies due to the grammatical process of inflection. There is archaeological evidence that in Latin worshippers wrote the nominative form of the god’s name as “Mithras”. Porphyry’s Greek text De Abstinentia (Περὶ ἀποχῆς ἐμψύχων), has a reference to the now-lost histories of the Mithraic mysteries by Euboulus and Pallas, the wording of which suggests that these authors treated the name “Mithra” as an indeclinable foreign word.[8]

In Sanskrit, mitra is an unusual name of the sun god, mostly known as “Surya” or “Aditya”, however.[9]

Iranian Mithra and Sanskrit Mitra are believed to come from the Indo-Iranian word mitrás, meaning “contract, agreement, covenant”.[10]

Modern historians have different conceptions about whether these names refer to the same god or not. John R. Hinnells has written of Mitra / Mithra / Mithras as a single deity, worshipped in several different religions.[11]

On the other hand, David Ulansey considers the bull-slaying Mithras to be a new god who began to be worshipped in the 1st century BCE, and to whom an old name was applied.[12]

Mary Boyce, an academic researcher on ancient Iranian religions, writes that even though Roman Mithraism seems to have had less Iranian content than ancient Romans or modern historians used to think, nonetheless “as the name Mithras alone shows, this content was of some importance”.[13]

Worshippers of Mithras had a complex system of seven grades of initiation and communal ritual meals. Initiates called themselves syndexioi, those “united by the handshake”.[14] They met in dedicated mithraea (singular mithraeum), underground temples that survive in large numbers. The cult appears to have had its center in Rome,[15] and was popular throughout the western half of the empire, as far south as Roman Africa and Numidia, as far east as Roman Dacia, as far north as Roman Britain,[16] and to a lesser extent in Roman Syria in the east.[17]

Mithraism is viewed as a rival of early Christianity.[18] In the 4th century, Mithraists faced persecution from Christians, and the religion was subsequently suppressed and eliminated in the Roman Empire by the end of the century.[19]

Numerous archaeological finds, including meeting places, monuments, and artifacts, have contributed to modern knowledge about Mithraism throughout the Roman Empire.[20] The iconic scenes of Mithras show him being born from a rock, slaughtering a bull, and sharing a banquet with the god Sol (the Sun).

About 420 sites have yielded materials related to the cult. Among the items found are about 1000 inscriptions, 700 examples of the bull-killing scene (tauroctony), and about 400 other monuments.[21](p xxi) It has been estimated that there would have been at least 680 mithraea in the city of Rome.[22]

No written narratives or theology from the religion survive; limited information can be derived from the inscriptions and brief or passing references in Greek and Latin literature. Interpretation of the physical evidence remains problematic and contested.[23]

The origins and spread of the Mysteries have been intensely debated among scholars and there are radically differing views on these issues.[24] According to Manfred Clauss, mysteries of Mithras were not practiced until the 1st century CE.[25]

According to Ulansey, the earliest evidence for the Mithraic mysteries places their appearance in the middle of the 1st century BCE: The historian Plutarch says that in 67 BCE the pirates of Cilicia (a province on the southeastern coast of Asia Minor, that provided sea access to adjacent Commagene) were practicing “secret rites” of Mithras.[26] According to C.M. Daniels,[27] whether any of this relates to the origins of the mysteries is unclear.[28] The unique underground temples or mithraea appear suddenly in the archaeology in the last quarter of the 1st century CE.[29]

Scholarship on Mithras begins with Franz Cumont, who published a two volume collection of source texts and images of monuments in French in 1894–1900, Textes et monuments figurés relatifs aux mystères de Mithra [French: Texts and Illustrated Monuments Relating to the Mysteries of Mithra].[30] An English translation of part of this work was published in 1903, with the title The Mysteries of Mithra.[31]

Cumont’s hypothesis, as the author summarizes it in the first 32 pages of his book, was that the Roman religion was “the Roman form of Mazdaism”,[32] the Persian state religion, disseminated from the East. He identified the ancient Aryan deity who appears in Persian literature as Mithras with the Hindu god Mitra of the Vedic hymns.[33] According to Cumont, the god Mithra came to Rome “accompanied by a large representation of the Mazdean Pantheon.”[34] Cumont considers that while the tradition “underwent some modification in the Occident … the alterations that it suffered were largely superficial.”[35]

Cumont’s theories came in for severe criticism from John R. Hinnells and R.L. Gordon at the First International Congress of Mithraic Studies held in 1971.[36] John Hinnells was unwilling to reject entirely the idea of Iranian origin,[37] but wrote: “we must now conclude that his reconstruction simply will not stand. It receives no support from the Iranian material and is in fact in conflict with the ideas of that tradition as they are represented in the extant texts. Above all, it is a theoretical reconstruction which does not accord with the actual Roman iconography.”[38]

He discussed Cumont’s reconstruction of the bull-slaying scene and stated “that the portrayal of Mithras given by Cumont is not merely unsupported by Iranian texts but is actually in serious conflict with known Iranian theology.”[39] Another paper by R.L. Gordon argued that Cumont severely distorted the available evidence by forcing the material to conform to his predetermined model of Zoroastrian origins. Gordon suggested that the theory of Persian origins was completely invalid and that the Mithraic mysteries in the West were an entirely new creation.[40]

Roger Beck theorizes that the cult was created in Rome, by a single founder who had some knowledge of both Greek and Oriental religion, but suggests that some of the ideas used may have passed through the Hellenistic kingdoms. He observes that “Mithras – moreover, a Mithras who was identified with the Greek Sun god Helios” was among the gods of the syncretic Greco-Armenian-Iranian royal cult at Nemrut, founded by Antiochus I of Commagene in the mid 1st century BCE.[41] While proposing the theory, Beck says that his scenario may be regarded as Cumontian in two ways. Firstly, because it looks again at Anatolia and Anatolians, and more importantly, because it hews back to the methodology first used by Cumont.[42]

Later history

The first important expansion of the mysteries in the Empire seems to have happened quite quickly, late in the reign of Antoninus Pius (b. 121 CE, d. 161 CE) and under Marcus Aurelius. By this time all the key elements of the mysteries were in place.[43]

Mithraism reached the apogee of its popularity during the 2nd and 3rd centuries, spreading at an “astonishing” rate at the same period when the worship of Sol Invictus was incorporated into the state-sponsored cults.[44][45] At this period a certain Pallas devoted a monograph to Mithras, and a little later Euboulus wrote a History of Mithras, although both works are now lost.[46] According to the 4th century Historia Augusta, the emperor Commodus participated in its mysteries[47] but it never became one of the state cults.[48]

The religion and its followers faced persecution in the 4th century from Christianization, and Mithraism came to an end at some point between its last decade and the 5th century. Ulansey states that “Mithraism declined with the rise to power of Christianity, until the beginning of the fifth century, when Christianity became strong enough to exterminate by force rival religions such as Mithraism.”[49]

According to Speidel, Christians fought fiercely with this feared enemy and suppressed it during the late 4th century. Mithraic sanctuaries were destroyed and religion was no longer a matter of personal choice.[50][51] According to L.H. Martin, Roman Mithraism came to an end with the anti-pagan decrees of the Christian emperor Theodosius during the last decade of the 4th century.[52]

Franz Cumont states that Mithraism may have survived in certain remote cantons of the Alps and Vosges into the 5th century.[53] According to Mark Humphries, the deliberate concealment of Mithraic cult objects in some areas suggests that precautions were being taken against Christian attacks. In areas like the Rhine frontier, barbarian invasions may have also played a role in the end of Mithraism.[54]

At some of the mithraeums that have been found below churches, such as the Santa Prisca Mithraeum and the San Clemente Mithraeum, the ground plan of the church above was made in a way to symbolize Christianity’s domination of Mithraism.[55] The cult disappeared earlier than that of Isis. Isis was still remembered in the Middle Ages as a pagan deity, but Mithras was already forgotten in late antiquity.[56]

Ulansey has proposed that Mithras seems to have been derived from the constellation of Perseus, which is positioned just above Taurus in the night sky. He sees iconographic and mythological parallels between the two figures: both are young heroes, carry a dagger, and wear a Phrygian cap.

He also mentions the similarity of the image of Perseus killing the Gorgon and the tauroctony, both figures being associated with caverns and both having connections to Persia as further evidence.[57]

Michael Speidel associates Mithras with the constellation of Orion because of the proximity to Taurus, and the consistent nature of the depiction of the figure as having wide shoulders, a garment flared at the hem, and narrowed at the waist with a belt, thus taking on the form of the constellation.[58]

Iconography

Much about the cult of Mithras is only known from reliefs and sculptures. There have been many attempts to interpret this material.

Mithras-worship in the Roman Empire was characterized by images of the god slaughtering a bull. Other images of Mithras are found in the Roman temples, for instance Mithras banqueting with Sol, and depictions of the birth of Mithras from a rock. But the image of bull-slaying (tauroctony) is always in the central niche.[59] Textual sources for a reconstruction of the theology behind this iconography are very rare.[6o]

The practice of depicting the god slaying a bull seems to be specific to Roman Mithraism. According to David Ulansey, this is “perhaps the most important example” of evident difference between Iranian and Roman traditions: “… there is no evidence that the Iranian god Mithra ever had anything to do with killing a bull.”[61]

Bull-slaying scene

In every mithraeum the centerpiece was a representation of Mithras killing a sacred bull, an act called the tauroctony.[62][63] The image may be a relief, or free-standing, and side details may be present or omitted. The centre-piece is Mithras clothed in Anatolian costume and wearing a Phrygian cap; who is kneeling on the exhausted bull, holding it by the nostrils[64] with his left hand, and stabbing it with his right.

As he does so, he looks over his shoulder towards the figure of Sol. A dog and a snake reach up towards the blood. A scorpion seizes the bull’s genitals. A raven is flying around or is sitting on the bull. One or three ears of wheat are seen coming out from the bull’s tail, sometimes from the wound. The bull was often white. The god is sitting on the bull in an unnatural way with his right leg constraining the bull’s hoof and the left leg is bent and resting on the bull’s back or flank.[65] The two torch-bearers are on either side are dressed like Mithras: Cautes with his torch pointing up, and Cautopates with his torch pointing down.[66][67] Sometimes Cautes and Cautopates carry shepherds’ crooks instead of torches.[68]

The event takes place in a cavern, into which Mithras has carried the bull, after having hunted it, ridden it and overwhelmed its strength.[69] Sometimes the cavern is surrounded by a circle, on which the twelve signs of the zodiac appear. Outside the cavern, top left, is Sol the sun, with his flaming crown, often driving a quadriga. A ray of light often reaches down to touch Mithras. At the top right is Luna, with her crescent moon, who may be depicted driving a biga.[70]

In some depictions, the central tauroctony is framed by a series of subsidiary scenes to the left, top and right, illustrating events in the Mithras narrative; Mithras being born from the rock, the water miracle, the hunting and riding of the bull, meeting Sol who kneels to him, shaking hands with Sol and sharing a meal of bull-parts with him, and ascending to the heavens in a chariot.[71]

In some instances, as is the case in the stucco icon at Santa Prisca Mithraeum in Rome, the god is shown heroically nude.[72]

Some of these reliefs were constructed so that they could be turned on an axis. On the back side was another, more elaborate feasting scene.

This indicates that the bull killing scene was used in the first part of the celebration, then the relief was turned, and the second scene was used in the second part of the celebration.[73]

Besides the main cult icon, a number of mithraea had several secondary tauroctonies, and some small portable versions, probably meant for private devotion, have also been found.[74]

According to Cumont, the imagery of the tauroctony was a Graeco-Roman representation of an event in Zoroastrian cosmogony described in a 9th-century Zoroastrian text, the Bundahishn. In this text the evil spirit Ahriman (not Mithra) slays the primordial creature Gavaevodata, which is represented as a bovine.[75]

Cumont held that a version of the myth must have existed in which Mithras, not Ahriman, killed the bovine. But according to Hinnells, no such variant of the myth is known, and that this is merely speculation: “In no known Iranian text [either Zoroastrian or otherwise] does Mithra slay a bull.”[76]

Banquet

The second most important scene after the tauroctony in Mithraic art is the so-called banquet scene.[77] The banquet scene features Mithras and Sol Invictus banqueting on the hide of the slaughtered bull.[78]

On the specific banquet scene on the Fiano Romano relief (pictured above), one of the torchbearers points a caduceus towards the base of an altar, where flames appear to spring up. Robert Turcan has argued that since the caduceus is an attribute of Mercury, and in mythology Mercury is depicted as a psychopomp, the eliciting of flames in this scene is referring to the dispatch of human souls and expressing the Mithraic doctrine on this matter.[79]

Turcan also connects this event to the tauroctony: The blood of the slain bull has soaked the ground at the base of the altar, and from the blood the souls are elicited in flames by the caduceus.[80]

Birth from a rock

Mithras is depicted as being born from a rock. He is shown as emerging from a rock, already in his youth, with a dagger in one hand and a torch in the other. He is nude, standing with his legs together, and is wearing a Phrygian cap.[81]

In some variations, he is shown coming out of the rock as a child, and in one holds a globe in one hand; sometimes a thunderbolt is seen. There are also depictions in which flames are shooting from the rock and also from Mithras’ cap. One statue had its base perforated so that it could serve as a fountain, and the base of another has the mask of a water god. Sometimes Mithras also has other weapons such as bows and arrows, and there are also animals such as dogs, serpents, dolphins, eagles, other birds, lions, crocodiles, lobsters and snails around.

On some reliefs, there is a bearded figure identified as the water god Oceanus, and on some there are the gods of the four winds. In these reliefs, the four elements could be invoked together. Sometimes Victoria, Luna, Sol, and Saturn also seem to play a role. Saturn in particular is often seen handing over the dagger or short sword to Mithras, used later in the tauroctony.[82]

In some depictions, Cautes and Cautopates are also present; sometimes they are depicted as shepherds.[83]

On some occasions, an amphora is seen, and a few instances show variations like an egg birth or a tree birth. Some interpretations show that the birth of Mithras was celebrated by lighting torches or candles.[84][85]

Lion-headed figure

One of the most characteristic and poorly-understood features of the Mysteries is the naked lion-headed figure often found in Mithraic temples, named by the modern scholars with descriptive terms such as leontocephaline (lion-headed) or leontocephalus (lion-head).

His body is a naked man’s, entwined by a serpent (or two serpents, like a caduceus), with the snake’s head often resting on the lion’s head. The lion’s mouth is often open.

He is usually represented as having four wings, two keys (sometimes a single key), and a sceptre in his hand. Sometimes the figure is standing on a globe inscribed with a diagonal cross. On the figure from the Ostia Antica Mithraeum, the four wings carry the symbols of the four seasons, and a thunderbolt is engraved on his chest. At the base of the statue are the hammer and tongs of Vulcan and Mercury’s cock and wand (caduceus).

A rare variation of the same figure is also found with a human head and a lion’s head emerging from its chest.[86][87]

Although animal-headed figures are prevalent in contemporary Egyptian and Gnostic mythological representations, no exact parallel to the Mithraic leontocephaline figure has been found.[88]

Based on dedicatory inscriptions for altars, the name of the figure is conjectured to be Arimanius, a Latinized form of the name Ahriman[89] – perplexingly, a demonic figure in the Zoroastrian pantheon.

Arimanius is known from inscriptions to have been a god in the Mithraic cult as seen, for example, in images from the Corpus Inscriptionum et Monumentorum Religionis Mithriacae such as CIMRM[90] 222 from Ostia, CIMRM 369 from Rome, and CIMRM[90] 1773 and 1775 from Pannonia.[91]

Some scholars identify the lion-man as Aion, or Zurvan, or Cronus, or Chronos, while others assert that it is a version of the Zoroastrian Ahriman or the more benign Vedic Aryaman.[92] Although the exact identity of the lion-headed figure is debated by scholars, it is largely agreed that the god is associated with time and seasonal change.[93]

Rituals and worship

According to M.J. Vermaseren and C.C. van Essen, the Mithraic New Year and the birthday of Mithras was on 25 December.[94][95] Beck disagreed strongly.[96] Clauss states:

“The Mithraic Mysteries had no public ceremonies of its own. The festival of Natalis Invicti, held on 25 December, was a general festival of the Sun, and by no means specific to the Mysteries of Mithras.”[97]

Mithraic initiates were required to swear an oath of secrecy and dedication.[98]

Mithras was thought to be a “warrior hero” similar to Greek heroes.[99]

Apparently, some grade rituals involved the recital of a catechism, wherein the initiate was asked a series of questions pertaining to the initiation symbolism and had to reply with specific answers. An example of such a catechism, apparently pertaining to the Leo grade, was discovered in a fragmentary Egyptian papyrus (Papyrus Berolinensis 21196).

Almost no Mithraic scripture or first-hand account of its highly secret rituals survives;[10o] with the exception of the aforementioned oath and catechism, and the document known as the Mithras Liturgy, from 4th century Egypt, whose status as a Mithraist text has been questioned by scholars including Franz Cumont.[101][102]

The walls of mithraea were commonly whitewashed, and where this survives, it tends to carry extensive repositories of graffiti; and these, together with inscriptions on Mithraic monuments, form the main source for Mithraic texts.[103]

It is clear from the archaeology of numerous mithraea that most rituals were associated with feasting – as eating utensils and food residues are almost invariably found. These tend to include both animal bones and also very large quantities of fruit residues.[104] The presence of large amounts of cherry-stones in particular would tend to confirm mid-summer (late June, early July) as a season especially associated with Mithraic festivities.

The Virunum album, in the form of an inscribed bronze plaque, records a Mithraic festival of commemoration as taking place on 26 June 184. Beck argues that religious celebrations on this date are indicative of special significance being given to the summer solstice; but this time of the year coincides with ancient recognition of the solar maximum at midsummer, when iconographically identical holidays such as Litha, Saint John’s Eve, and Jāņi are also observed.

For their feasts, Mithraic initiates reclined on stone benches arranged along the longer sides of the mithraeum – typically there might be room for 15 to 30 diners, but very rarely many more than 40 men.[105] Counterpart dining rooms, or triclinia, were to be found above ground in the precincts of almost any temple or religious sanctuary in the Roman empire, and such rooms were commonly used for their regular feasts by Roman ‘clubs’, or collegia.

Mithraic feasts probably performed a very similar function for Mithraists as the collegia did for those entitled to join them; indeed, since qualification for Roman collegia tended to be restricted to particular families, localities or traditional trades, Mithraism may have functioned in part as providing clubs for the unclubbed.[106] The size of the mithraeum is not necessarily an indication of the size of the congregation.[107]

Mithraeum

Temples of Mithras are sunk below ground, windowless, and very distinctive. In cities, the basement of an apartment block might be converted; elsewhere they might be excavated and vaulted over, or converted from a natural cave. Mithraic temples are common in the empire; although unevenly distributed, with considerable numbers found in Rome, Ostia, Numidia, Dalmatia, Britain and along the Rhine/Danube frontier, while being somewhat less common in Greece, Egypt, and Syria.[108]

According to Walter Burkert, the secret character of Mithraic rituals meant that Mithraism could only be practiced within a Mithraeum.[109] Some new finds at Tienen show evidence of large-scale feasting and suggest that the mystery religion may not have been as secretive as was generally believed.[110]

For the most part, mithraea tend to be small, externally undistinguished, and cheaply constructed; the cult generally preferring to create a new centre rather than expand an existing one. The mithraeum represented the cave to which Mithras carried and then killed the bull; and where stone vaulting could not be afforded, the effect would be imitated with lath and plaster.

They are commonly located close to springs or streams; fresh water appears to have been required for some Mithraic rituals, and a basin is often incorporated into the structure.[111] There is usually a narthex or ante-chamber at the entrance, and often other ancillary rooms for storage and the preparation of food.

The extant mithraea present us with actual physical remains of the architectural structures of the sacred spaces of the Mithraic cult. Mithraeum is a modern coinage and mithraists referred to their sacred structures as speleum or antrum (cave), crypta (underground hallway or corridor), fanum (sacred or holy place), or even templum (a temple or a sacred space).[112]

In their basic form, mithraea were entirely different from the temples and shrines of other cults. In the standard pattern of Roman religious precincts, the temple building functioned as a house for the god, who was intended to be able to view, through the opened doors and columnar portico, sacrificial worship being offered on an altar set in an open courtyard – potentially accessible not only to initiates of the cult, but also to colitores or non-initiated worshippers.[113] Mithraea were the antithesis of this.[114]

David Ulansey finds astronomical evidence from the mithraeum itself.[115] He reminds us that the Platonic writer Porphyry wrote in the 3rd century CE that the cave-like temple Mithraea depicted “an image of the world”[116] and that Zoroaster consecrated a cave resembling the world fabricated by Mithras.[117] The ceiling of the Caesarea Maritima Mithraeum retains traces of blue paint, which may mean the ceiling was painted to depict the sky and the stars.[118]

Membership and Initiation

Only male names appear in surviving inscribed membership lists. Historians including Cumont and Richard Gordon have concluded that the cult was for men only.[119][120]

The ancient scholar Porphyry refers to female initiates in Mithraic rites.[121] The early 20th-century historian A.S. Geden wrote that this may be due to a misunderstanding.[122] According to Geden, while the participation of women in the ritual was not unknown in the Eastern cults, the predominant military influence in Mithraism makes it unlikely in this instance.[122] It has recently been suggested by David Jonathan that “Women were involved with Mithraic groups in at least some locations of the empire.”[123]

Soldiers were strongly represented amongst Mithraists, and also merchants, customs officials and minor bureaucrats. Few, if any, initiates came from leading aristocratic or senatorial families until the ‘pagan revival’ of the mid-4th century; but there were always considerable numbers of freedmen and slaves.[124]

In the Suda under the entry Mithras, it states that “No one was permitted to be initiated into them (the mysteries of Mithras), until he should show himself holy and steadfast by undergoing several graduated tests.”[125] Gregory Nazianzen refers to the “tests in the mysteries of Mithras”.[126]

There were seven grades of initiation into Mithraism, which are listed by St. Jerome.[127] Manfred Clauss states that the number of grades, seven, must be connected to the planets. A mosaic in the Mithraeum of Felicissimus, Ostia Antica depicts these grades, with symbolic emblems that are connected either to the grades or are symbols of the planets. The grades also have an inscription beside them commending each grade into the protection of the different planetary gods.[128] In ascending order of importance, the initiatory grades were:

| Name | Symbols | Planet or tutelary deity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Corax, Corux, or Corvex (raven or crow) | Beaker, caduceus | Mercury |

| 2 | Nymphus, Nymphobus (bridegroom) | Lamp, hand bell, veil, circlet or diadem | Venus |

| 3 | Miles (soldier) | Pouch, helmet, lance, drum, belt, breastplate | Mars |

| 4 | Leo (lion) | Batillum, sistrum, laurel wreath, thunderbolts | Jupiter |

| 5 | Perses (Persian) | Hooked sword, Phrygian cap, sickle, crescent moon, stars, sling, pouch | Luna |

| 6 | Heliodromus (sun-runner) | Torch, images of Helios, whip, robes | Sol |

| 7 | Pater (father) | Patera, mitre, shepherd's staff, garnet or ruby ring, chasuble or cape, elaborate jewel- encrusted robes, with metallic threads | Saturn |

The highest grade, pater, is by far the most common one found on dedications and inscriptions – and it would appear not to have been unusual for a mithraeum to have several men with this grade. The form pater patrum (father of fathers) is often found, which appears to indicate the pater with primary status. There are several examples of persons, commonly those of higher social status, joining a mithraeum with the status pater – especially in Rome during the ‘pagan revival’ of the 4th century. It has been suggested that some mithraea may have awarded honorary pater status to sympathetic dignitaries.[129]

The initiate into each grade appears to have been required to undertake a specific ordeal or test,[130] involving exposure to heat, cold or threatened peril. An ‘ordeal pit’, dating to the early 3rd century, has been identified in the mithraeum at Carrawburgh. Accounts of the cruelty of the emperor Commodus describes his amusing himself by enacting Mithraic initiation ordeals in homicidal form. By the later 3rd century, the enacted trials appear to have been abated in rigor, as ‘ordeal pits’ were floored over.

Admission into the community was completed with a handshake with the pater, just as Mithras and Sol shook hands. The initiates were thus referred to as syndexioi (those united by the handshake). The term is used in an inscription by Proficentius[131] and derided by Firmicus Maternus in De errore profanarum religionum,[132] a 4th century Christian work attacking paganism.[133] In ancient Iran, taking the right hand was the traditional way of concluding a treaty or signifying some solemn understanding between two parties.[134]

Ritual re-enactments

Activities of the most prominent deities in Mithraic scenes, Sol and Mithras, were imitated in rituals by the two most senior officers in the cult’s hierarchy, the Pater and the Heliodromus.[135] The initiates held a sacramental banquet, replicating the feast of Mithras and Sol.[136]

Reliefs on a cup found in Mainz[137][138] appear to depict a Mithraic initiation. On the cup, the initiate is depicted as being led into a location where a Pater would be seated in the guise of Mithras with a drawn bow. Accompanying the initiate is a mystagogue, who explains the symbolism and theology to the initiate. The Rite is thought to re-enact what has come to be called the ‘Water Miracle’, in which Mithras fires a bolt into a rock, and from the rock now spouts water.

Roger Beck has hypothesized a third processional Mithraic ritual, based on the Mainz cup and Porphyrys. This scene, called ‘Procession of the Sun-Runner’, shows the Heliodromus escorted by two figures representing Cautes and Cautopates (see below) and preceded by an initiate of the grade Miles leading a ritual enactment of the solar journey around the mithraeum, which was intended to represent the cosmos.[139]

Consequently, it has been argued that most Mithraic rituals involved a re-enactment by the initiates of episodes in the Mithras narrative,[140] a narrative whose main elements were: birth from the rock, striking water from stone with an arrow shot, the killing of the bull, Sol’s submission to Mithras, Mithras and Sol feasting on the bull, the ascent of Mithras to heaven in a chariot. A noticeable feature of this narrative (and of its regular depiction in surviving sets of relief carvings) is the absence of female personages (the sole exception being Luna watching the tauroctony in the upper corner opposite Helios, and the presumable presence of Venus as patroness of the nymphus grade).[140]

Religious parallels

The cult of Mithras was part of the syncretic nature of ancient Roman religion. Almost all Mithraea contain statues dedicated to gods of other cults, and it is common to find inscriptions dedicated to Mithras in other sanctuaries, especially those of Jupiter Dolichenus.[140] Mithraism was not an alternative to Rome’s other traditional religions, but was one of many forms of religious practice, and many Mithraic initiates can also be found participating in the civic religion, and as initiates of other mystery cults.[141]

Early Christian apologists noted similarities between Mithraic and Christian rituals, but nonetheless took an extremely negative view of Mithraism: they interpreted Mithraic rituals as evil copies of Christian ones.[142][143] For instance, Tertullian wrote that as a prelude to the Mithraic initiation ceremony, the initiate was given a ritual bath and at the end of the ceremony, received a mark on the forehead. He described these rites as a diabolical counterfeit of the baptism and chrismation of Christians.[144] Justin Martyr contrasted Mithraic initiation communion with the Eucharist:[145]

Wherefore also the evil demons in mimicry have handed down that the same thing should be done in the Mysteries of Mithras. For that bread and a cup of water are in these mysteries set before the initiate with certain speeches you either know or can learn.[146]

Monuments in the Danube area depict Mithras shooting a bow at a rock in the presence of the torch-bearers, apparently to encourage water to come forth. Clauss states that, after the ritual meal, this “water-miracle offers the clearest parallel with Christianity”.[147]

Tertullian states that followers of Mithras were marked on their forehead in an unspecified manner.[148] There is no indication that this mark was made in the form of a cross, or a branding, or a tattoo, or a permanent mark of any kind.[149] The symbol of a circle with a diagonal cross inscribed within it is commonly found in Mithraea, especially in association with the Leontocephaline figure.

It is often stated (e.g. by Encyclopaedia Britannica,[150][151] the Catholic Encyclopedia,[152][153] and others[154][155]) that Mithras was born on December 25. Beck (1987)[156] argues that this is unproven. He writes:

“The only evidence for it is the celebration of the birthday of Invictus on that date in Calendar of Philocalus. Invictus is of course Sol Invictus, Aurelian’s sun god. It does not follow that a different, earlier, and unofficial sun god, Sol Invictus Mithras, was necessarily or even probably, born on that day too.”[157], n. 12 [158]

Meanwhile, in modern-day Iran, the original homeland of Mithra, its religious followers celebrate a traditional feast of his birth. The present-day Iran Chamber Society’s Ramona Shashaani claims that Christians borrowed the 25th December date from this ‘Persian’ (i.e. Parsee = Zoroastrian) tradition:[159]

While Christians around the world are preparing to celebrate Christmas on Dec. 25th, the Persians are getting ready to tribute one of their most festive celebrations on Dec. 21st, the eve of winter solstice, the longest night and shortest day of the year. In Iran this night is called Shab-e Yaldaa, also known as Shab-e Chelleh, which refers to the birthday or rebirth of the sun.

… Yaldaa is chiefly related to Mehr Yazat; it is the night of the birth of the unconquerable sun, Mehr or Mithra, meaning love and sun, and has been celebrated by the followers of Mithraism as early as 5000 BC

… But in the [Roman-controlled areas] 4th century AD, because of some errors in counting the leap year, the birthday of Mithra shifted to 25th of December and was established as such.[160]

According to Mary Boyce, Mithraism was a potent enemy for Christianity in the West, though she is sceptical about its hold in the East.[161][162][163]

F. Coarelli (1979) has tabulated forty actual or possible Mithraea and estimated that Rome would have had “not less than 680–690” mithraea.[164][165]

L.M. Hopfe states that more than 400 Mithraic sites have been found.

These sites are spread all over the Roman empire from places as far as Dura-Europos in the east, and England in the west. He, too, says that Mithraism may have been a rival of Christianity.[166] David Ulansey thinks Renan’s statement “somewhat exaggerated”,[167] but does consider Mithraism “one of Christianity’s major competitors in the Roman Empire”.[168]

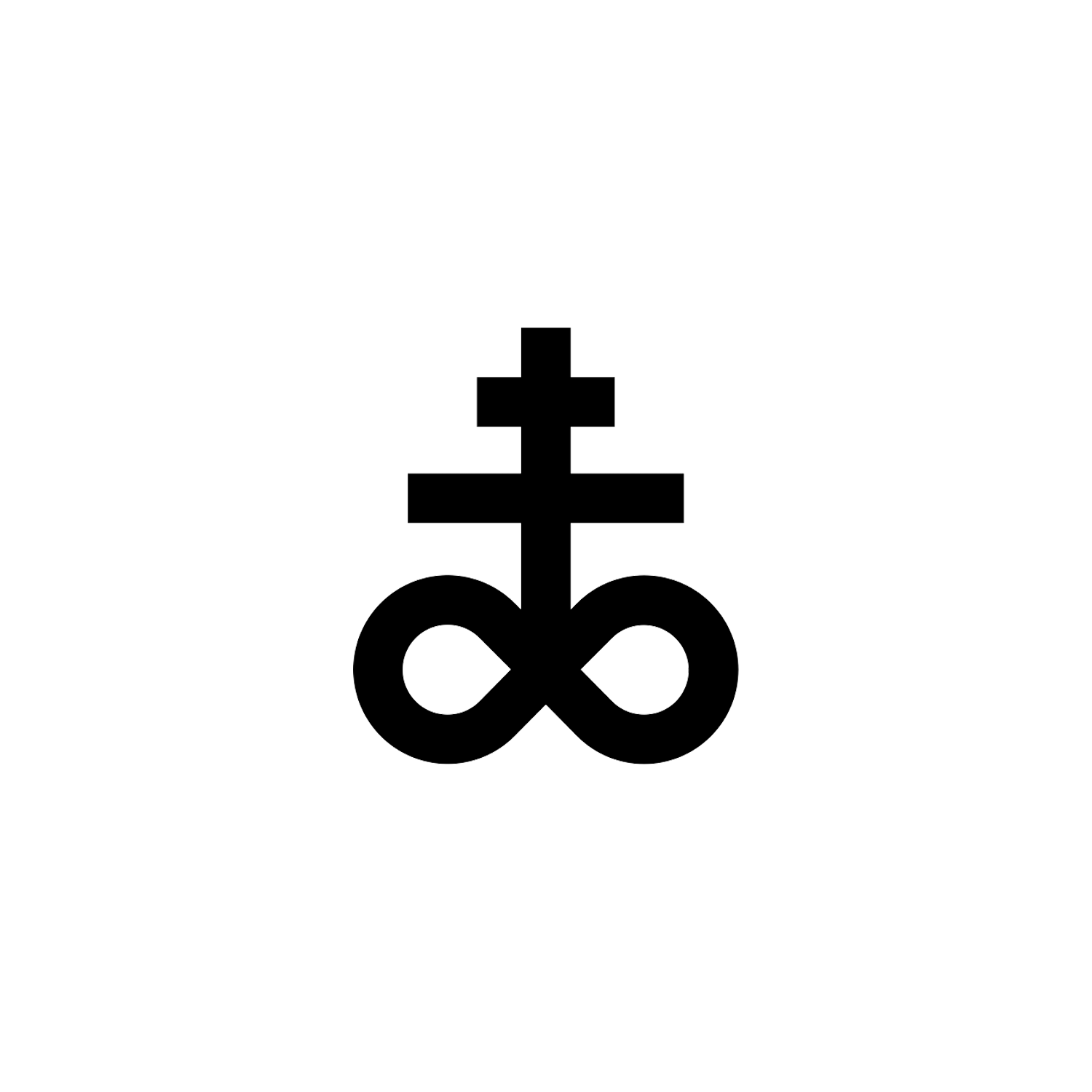

Symbol of Mithras

The symbol representing Mithras or the Cult of Mithras is most commonly associated with the bull, more precisely the tauroctony (slaying of the bull).

The bull is believed to be a specifically Roman symbol for Mithras, as scholars have noted that there is no evidence of any bull iconography relating to the Iranian god Mithra. The second most important scene in Mithraic iconography is the Banquet with the Sun which we covered earlier.

Other symbols can include the sun, albeit incorrectly as it is associated with Sol/Helios, and the Phrygian Cap. Individual grades of initiation into Mithraism have specific symbols, described in the ‘Membership and Initiation’ section of this article. Mithras in iconography is most prominently pictured with the Sun to the left and the Moon to the right.

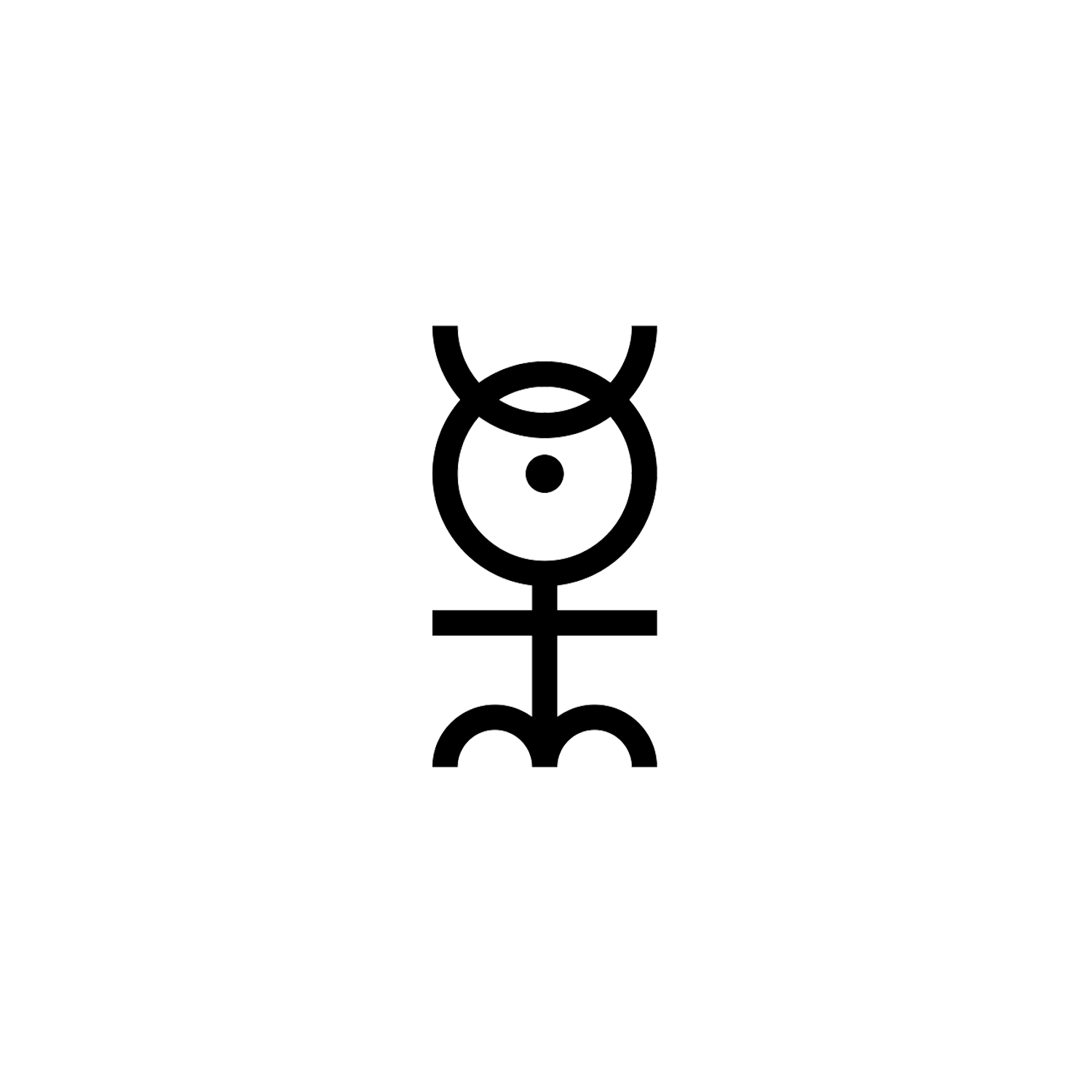

In modern times there is a glyph circulating online, claiming to represent Mithras, which is almost identical to the Hieroglyphic Monad. This symbol has no historic or symbolic relation to the Cult of Mithras and appears to be an invention/fabrication of an unknown designer in the last several years.

Conclusion

Mithraism was an enigmatic cult religion that flourished in the Roman Empire between the 1st and 4th centuries CE. Highly secretive by nature, historical understanding is challenged by the minimal record we have inherited about this fascinating cult.

References are scant, anecdotal, and often biased by religious prejudice.

Archaeology has expanded our view of Mithraism, though it is subject to interpretations and debate. Just what Mithraism was — its origins, practices, and impact — are all open to interpretation.

Mysterious, strange, and fundamentally “foreign,” there is far more that we do not understand about this cult than we do. That Mithras was imported, borrowed, or culturally interpreted from the East, seems likely, though just how authentic or how constructed it was from those roots is unknown.

Why it flourished in the later Roman empire, is an enduring conundrum. Evidently the great pending question on this topic, what Mithraism offered Romans, we may never understand and have an answer to.

References are still being cataloged. Check back soon.

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.