Ouroboros

Ouroboros

Also spelled as Uroboros.

Overview

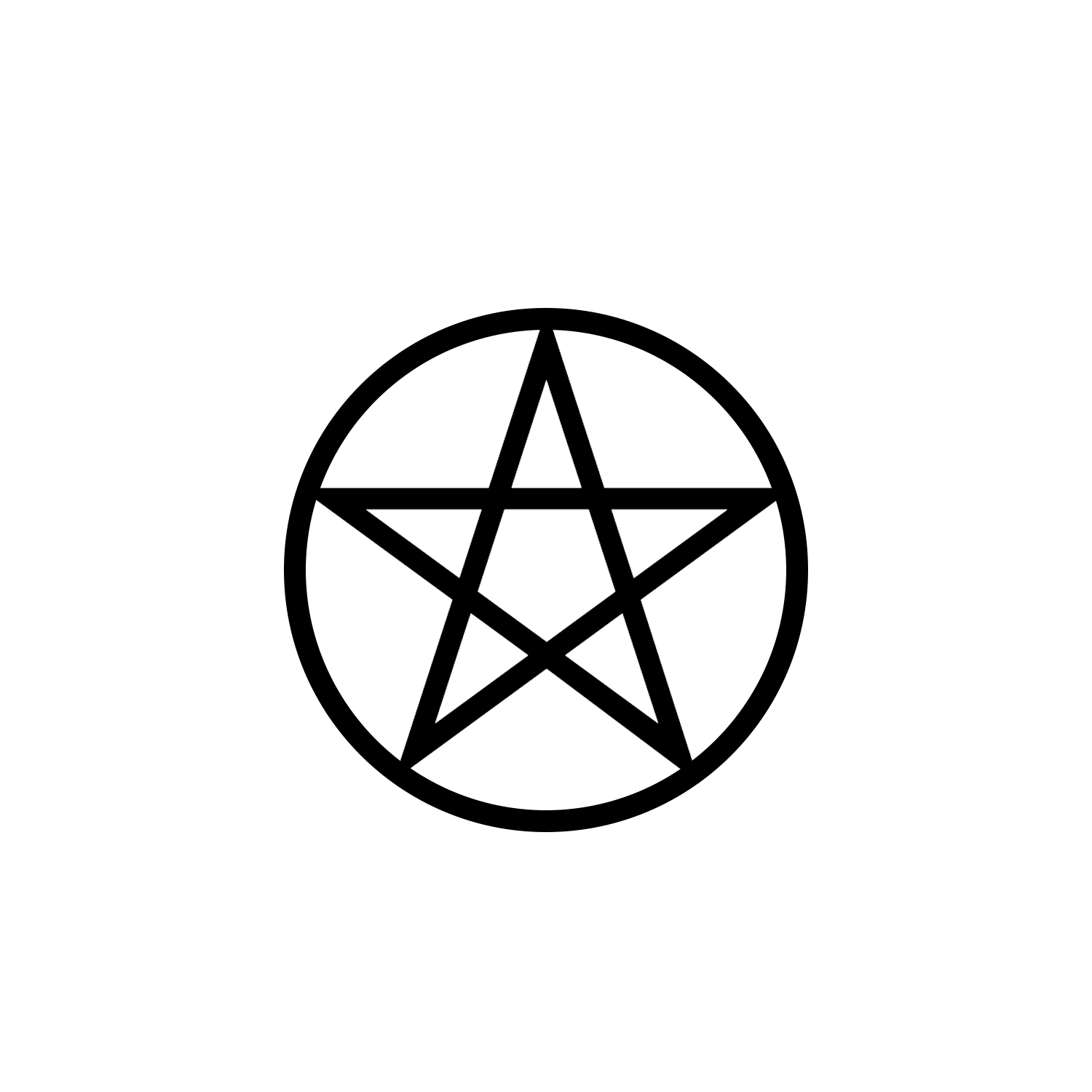

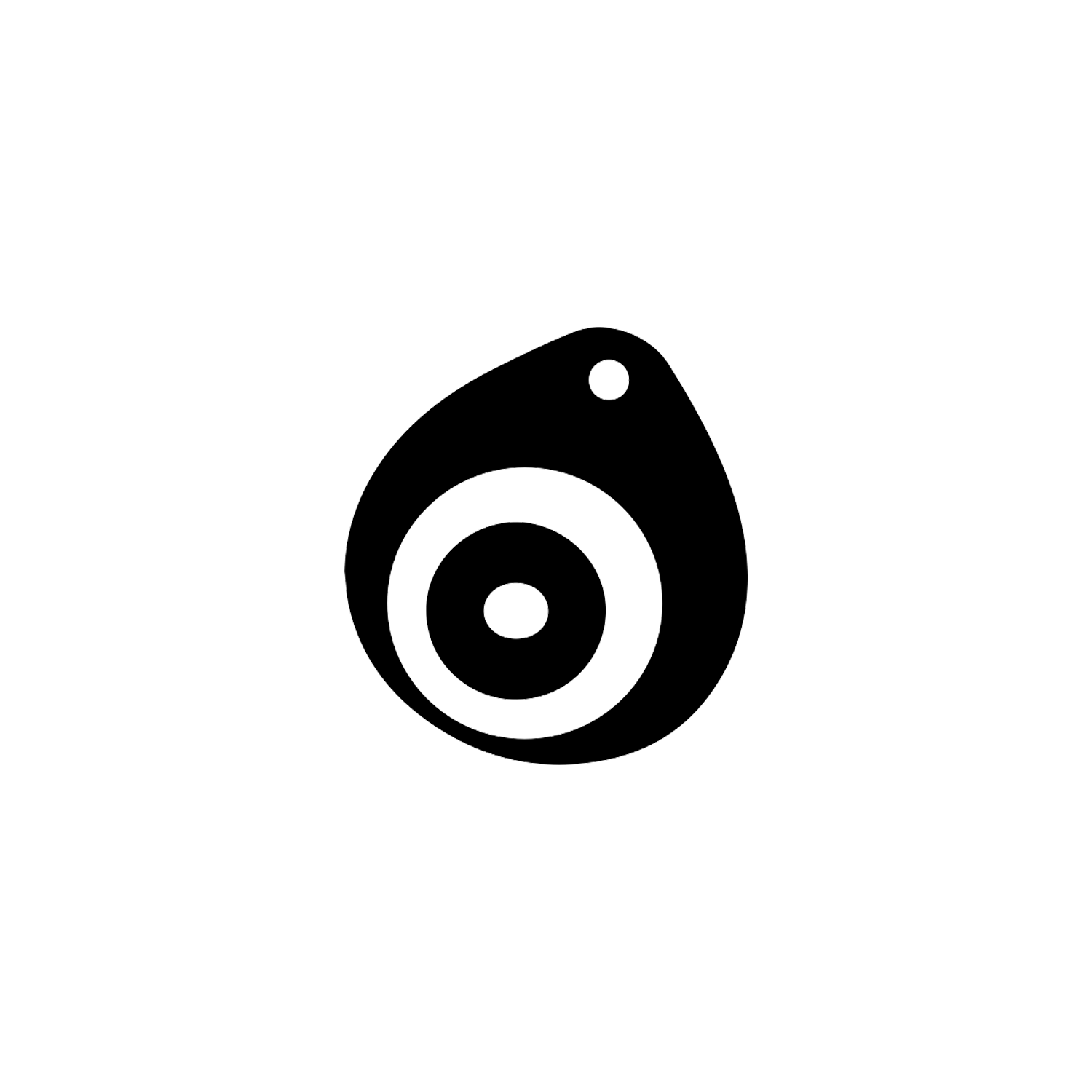

The ouroboros or uroboros (/ˌjʊərəˈbɒrəs/) is an ancient symbol depicting a serpent or dragon[1] eating its own tail.

The symbol entered Western tradition via ancient Egyptian iconography and the Greek magical tradition. It was adopted as a symbol in Gnosticism and Hermeticism and most notably in alchemy. Some snakes, such as rat snakes, have been known to consume themselves.[2]

The ouroboros is often interpreted as a symbol for eternal cyclic renewal or a cycle of life, death and rebirth; the snake’s skin-sloughing symbolises the transmigration of souls. The snake biting its own tail is a fertility symbol in some religions: the tail is a phallic symbol and the mouth is a yonic or womb-like symbol.[3]

Origin and Meaning

The term derives from Ancient Greek οὐροβόρος,[4] from οὐρά oura ‘tail’ plus -βορός -boros ‘-eating’.[5][6]

One of the earliest known ouroboros motifs is found in the Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld, an ancient Egyptian funerary text in KV62, the tomb of Tutankhamun, in the 14th century BCE. The text concerns the actions of Ra and his union with Osiris in the underworld.

The ouroboros is depicted twice on the figure: holding their tails in their mouths, one encircling the head and upper chest, the other surrounding the feet of a large figure, which may represent the unified Ra-Osiris (Osiris born again as Ra). Both serpents are manifestations of the deity Mehen, who in other funerary texts protects Ra in his underworld journey. The whole divine figure represents the beginning and the end of time.[7]

According to leading Egyptologist Jan Assmann, the symbol “refers to the mystery of cyclical time, which flows back into itself”. The ancient Egyptians understood time as a series of repetitive cycles, instead of something linear and constantly evolving; and central to this idea was the flooding of the Nile and the journey of the sun.

The ouroboros appears elsewhere in Egyptian sources, where, like many Egyptian serpent deities, it represents the formless disorder that surrounds the orderly world and is involved in that world’s periodic renewal.[8]

In ancient Egypt, the ouroboros is sometimes considered to represent the primordial snake, called Sata that surrounds the world, protecting it from the cosmic enemies. The Egyptian Book of the Dead quotes: “I’m Sata, I die and I can be born every day, I’m Sata that lives in the most remote regions of the world”.

The symbol persisted from Egyptian into Roman times, when it frequently appeared on magical talismans, sometimes in combination with other magical emblems.[9] The 4th-century CE Latin commentator Servius was aware of the Egyptian use of the symbol, noting that the image of a snake biting its tail represents the cyclical nature of the year.[10]

Gnosticism and Alchemy

In Gnosticism, a serpent biting its tail symbolised eternity and the soul of the world.[11] The Gnostic Pistis Sophia (c. 400 CE) describes the ouroboros as a twelve-part dragon surrounding the world with its tail in its mouth.[12]

Like the sun, the ouroboros underwent a journey of its own. From Egypt, it found its way to the Greek alchemists of Hellenistic Alexandria. In the Chrysopoeia (transmutation into gold) of Cleopatra, the ouroboros appears slightly differently.

Known as the oldest allegorical symbol in alchemy, the ouroboros in represented the concept of eternity and endless return, as well as the unity of time’s beginning and end, rather than the Egypt-specific journeys of the sun and the Nile. Elsewhere on the papyrus, in a double ring, appears the complete maxim, of which ‘One is All’ is only a part: ‘One is All, and by it All, and for it All’, it reads, ‘and if it does not contain All, then All is Nothing’.

The famous ouroboros drawing from the early alchemical text, The Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra (Κλεοπάτρας χρυσοποιία), probably originally dating to the 3rd century Alexandria, but first known in a 10th-century copy, encloses the words hen to pan (ἓν τὸ πᾶν), “the all is one”.

Its black and white halves may perhaps represent a Gnostic duality of existence, analogous to the Taoist yin and yang symbol.[13] The chrysopoeia ouroboros of Cleopatra the Alchemist is one of the oldest images of the ouroboros to be linked with the legendary opus of the alchemists, the philosopher’s stone.

A 15th-century alchemical manuscript, The Aurora Consurgens, features the ouroboros, where it is used among symbols of the sun, moon, and mercury.[14]

Jungian psychology

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung saw the ouroboros as an archetype and the basic mandala of alchemy. Jung also defined the relationship of the ouroboros to alchemy: Carl Jung, Collected Works, Vol. 14 para. 513.

The alchemists, who in their own way knew more about the nature of the individuation process than we moderns do, expressed this paradox through the symbol of the Ouroboros, the snake that eats its own tail. The Ouroboros has been said to have a meaning of infinity or wholeness. In the age-old image of the Ouroboros lies the thought of devouring oneself and turning oneself into a circulatory process, for it was clear to the more astute alchemists that the prima materia of the art was man himself.

The Ouroboros is a dramatic symbol for the integration and assimilation of the opposite, i.e. of the shadow. This ‘feedback’ process is at the same time a symbol of immortality since it is said of the Ouroboros that he slays himself and brings himself to life, fertilizes himself, and gives birth to himself.

He symbolizes the One, who proceeds from the clash of opposites, and he, therefore, constitutes the secret of the prima materia which … unquestionably stems from man’s unconscious.

The Jungian psychologist Erich Neumann writes of it as a representation of the pre-ego “dawn state”, depicting the undifferentiated infancy experience of both mankind and the individual child.[15]

Mythological Serpents

In Norse mythology, the ouroboros appears as the serpent Jörmungandr, one of the three children of Loki and Angrboda, which grew so large that it could encircle the world and grasp its tail in its teeth.

As a result of it surrounding Midgard (the Earth) it is referred to as the World Serpent. Jörmungandr releasing its tail is one of the signs of the beginning of Ragnarök (the final battle of the world).

In the legends of Ragnar Lodbrok, such as Ragnarssona þáttr, the Geatish king Herraud gives a small lindworm as a gift to his daughter Þóra Town-Hart after which it grows into a large serpent which encircles the girl’s bower and bites itself in the tail. The serpent is slain by Ragnar Lodbrok who marries Þóra. Ragnar later has a son with another woman named Kráka and this son is born with the image of a white snake in one eye. This snake encircled the iris and bit itself in the tail, and the son was named Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye.[16]

It is a common belief among indigenous people of the tropical lowlands of South America that waters at the edge of the world-disc are encircled by a snake, often an anaconda, biting its own tail.[17]

The ouroboros has certain features in common with the Biblical Leviathan. According to the Zohar, the Leviathan is a singular creature with no mate, “its tail is placed in its mouth”, while Rashi on Baba Batra 74b describes it as “twisting around and encompassing the entire world”. The identification appears to go back as far as the poems of Kalir in the 6th–7th centuries.

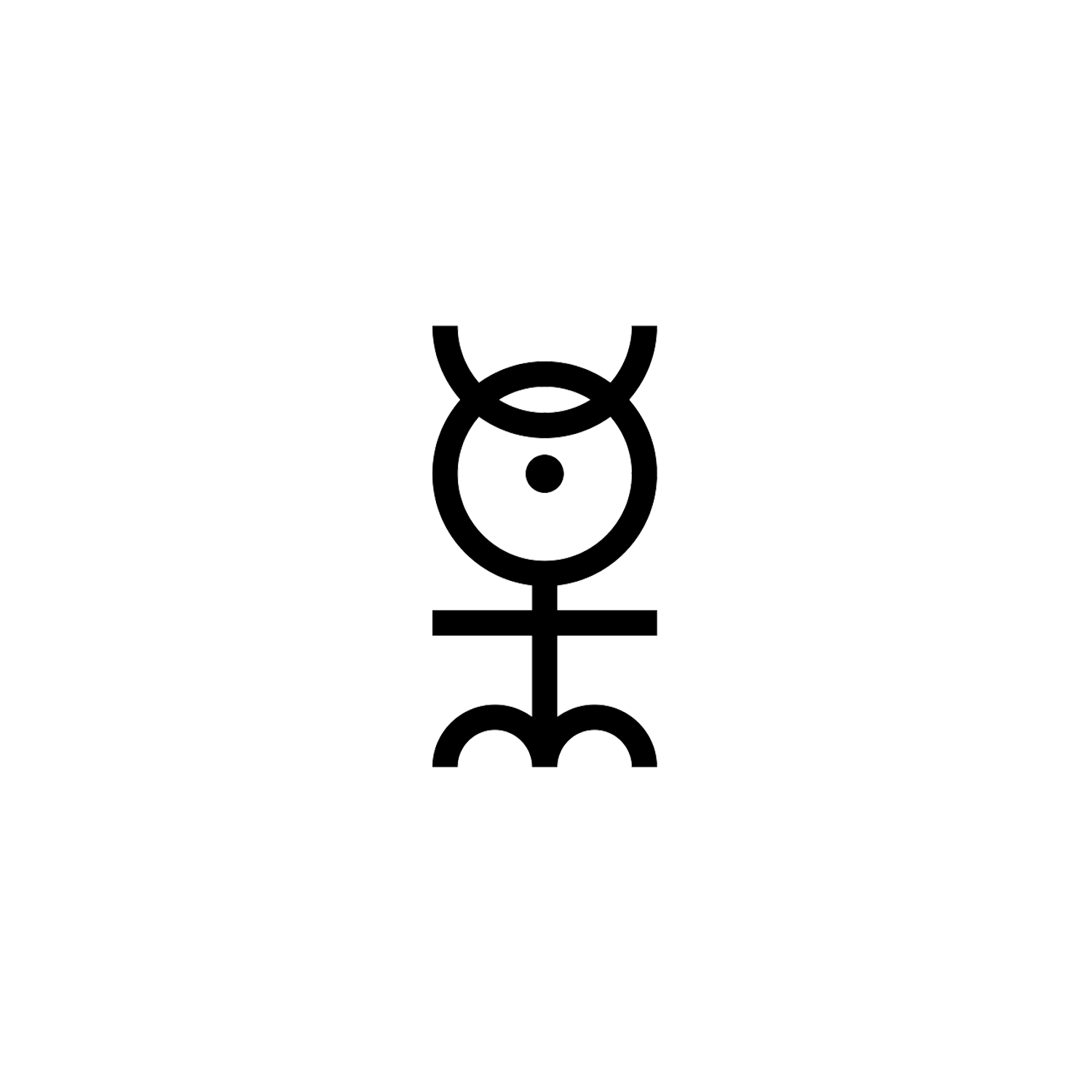

Ouroboros symbolism has been used to describe the Kundalini.[18] According to the medieval Yoga-kundalini Upanishad: “The divine power, Kundalini, shines like the stem of a young lotus; like a snake, coiled round upon herself she holds her tail in her mouth and lies resting half asleep as the base of the body” (1.82).[19]

The Kundalini is most commonly symbolised with the Caduceus. Some scholars associate the ouroboros image as a reference to the “cycle of samsara”.[20]

Conclusion

Ouroboros, an emblematic serpent of ancient Egypt and Greece represented with its tail in its mouth, continually devouring itself and being reborn.

As a gnostic and alchemical symbol, the Ouroboros expresses the unity of all things, material and spiritual, which never disappear but perpetually change form in an eternal cycle of destruction and re-creation.

[1] "Salvador Dalí: Alchimie des Philosophes | The Ouroboros". Academic Commons. Willamette University.

[2] Mattison, Chris (2007). The New Encyclopedia of Snakes. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-691-13295-2.

[3] Arien Mack (1999). Humans and Other Animals. Ohio State University Press. p. 359.

[4] Liddell & Scott (1940), οὐροβόρος

[5] Liddell & Scott (1940), οὐρά

[6] Liddell & Scott (1940), βορά

[7] Hornung, Erik. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Cornell University Press, 1999. pp. 38, 77–78

[8] Hornung, Erik (1982). Conceptions of God in Egypt: The One and the Many. Cornell University Press. pp. 163–64.

[9] Hornung, Erik (2002). The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West. p. 58. Cornell University Press.

[10] Servius, note to Aeneid 5.85: "according to the Egyptians, before the invention of the alphabet the year was symbolized by a picture, a serpent biting its own tail because it recurs on itself" (annus secundum Aegyptios indicabatur ante inventas litteras picto dracone caudam suam mordente, quia in se recurrit), as cited by Danuta Shanzer, A Philosophical and Literary Commentary on Martianus Capella's De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii Book 1 (University of California Press, 1986), p. 159.

[11] Origen, Contra Celsum 6.25.

[12] Hornung, Erik (2002). The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West. p. 76. Cornell University Press.

[13] Eliade, Mircea (1976). Occultism, Witchcraft, and Cultural Fashions. Chicago and London: U of Chicago Press. pp. 55, 93–113.

[14] Bekhrad, Joobin. "The ancient symbol that spanned millennia". BBC.

[15] Neumann, Erich. (1995). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Bollington series XLII: Princeton University Press. Originally published in German in 1949.

[16] Jurich, Marilyn (1998). Scheherazade's Sisters: Trickster Heroines and Their Stories in World Literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29724-3.

[17] Roe, Peter (1986), The Cosmic Zygote, Rutgers University Press

[18] Henneberg, Maciej; Saniotis, Arthur (24 March 2016). The Dynamic Human. Bentham Science Publishers. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-68108-235-6.

[19] Mahony, William K. (1 January 1998). The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination. SUNY Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-7914-3579-3.

[20] "When Shakti is united with Shiva, she is a radiant, gentle goddess; but when she is separated from him, she turns into a terrible, destructive fury. She is the endless Ouroboros, the dragon biting its own tail, symbolizing the cycle of samsara." Storl, Wolf-Dieter (2004). Shiva: The Wild God of Power and Ecstasy. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-59477-780-6.

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.