Typhon

Typhon

Also referred to as Typhos and Typhoan.

Overview

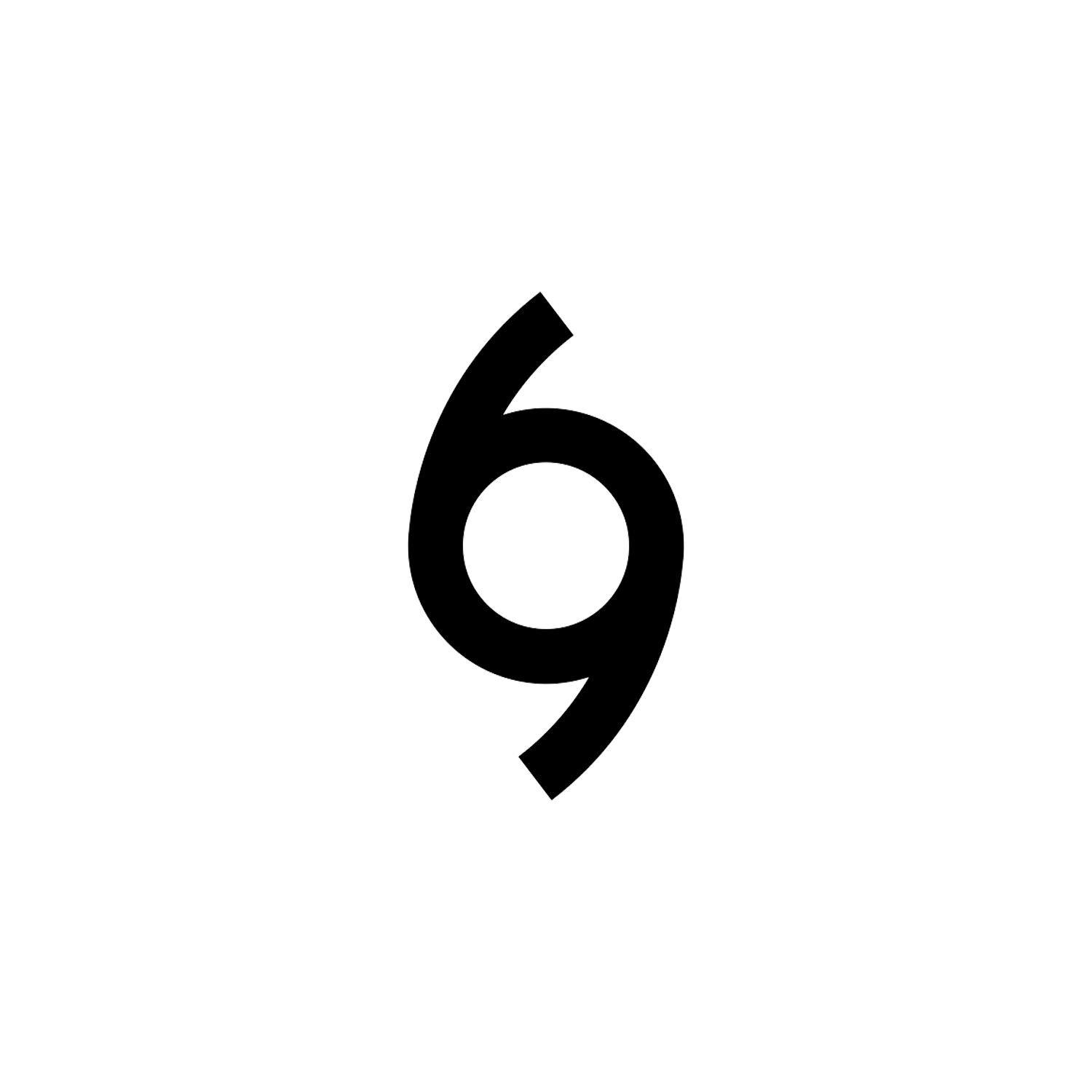

The Typhon symbol looks like the number six with a curved lower tail. Typhon comes from the Ancient Greek mythology and has been described as the father of all monsters. A half-human, half-winged beast with serpent heads springing out of his shoulder.

Origin and Meaning

Typhon (/ˈtaɪfɒn, -fən/; Ancient Greek: Τυφῶν, romanized: Typhôn, [tyːpʰɔ̂ːn]), also Typhoeus (/taɪˈfiːəs/; Τυφωεύς, Typhōeús), Typhaon (Τυφάων, Typháōn) or Typhos (Τυφώς, Typhṓs), was a monstrous serpentine giant and one of the deadliest creatures in Greek mythology. According to Hesiod, Typhon was the son of Gaia and Tartarus. However, one source has Typhon as the son of Hera alone, while another makes Typhon the offspring of Cronus. Typhon and his mate Echidna were the progenitors of many famous monsters.

Typhon attempted to overthrow Zeus for the supremacy of the cosmos. The two fought a cataclysmic battle, which Zeus finally won with the aid of his thunderbolts. Defeated, Typhon was cast into Tartarus, or buried underneath Mount Etna, or in later accounts, the island of Ischia.

Typhon mythology is part of the Greek succession myth, which explained how Zeus came to rule the gods. Typhon’s story is also connected with that of Python (the serpent killed by Apollo), and both stories probably derived from several Near Eastern antecedents. Typhon was (from c. 500 BC) also identified with the Egyptian god of destruction Set. In later accounts, Typhon was often confused with the Giants.

According to Hesiod’s Theogony (c. 8th – 7th century BC), Typhon was the son of Gaia (Earth) and Tartarus: “when Zeus had driven the Titans from heaven, huge Earth bore her youngest child Typhoeus of the love of Tartarus, by the aid of golden Aphrodite”.[1] The mythographer Apollodorus (1st or 2nd century AD) adds that Gaia bore Typhon in anger at the gods for their destruction of her offspring the Giants.[2]

Numerous other sources mention Typhon as being the offspring of Gaia, or simply “earth-born”, with no mention of Tartarus.[3] However, according to the Homeric Hymn to Apollo (6th century BC), Typhon was the child of Hera alone.[4] Hera, angry at Zeus for having given birth to Athena by himself, prayed to Gaia, Uranus, and the Titans, to give her a son stronger than Zeus, then slapped the ground and became pregnant. Hera gave the infant Typhon to the serpent Python to raise, and Typhon grew up to become a great bane to mortals.[5]

According to Hesiod, Typhon was “terrible, outrageous and lawless”,[6] immensely powerful, and on his shoulders were one hundred snake heads, that emitted fire and every kind of noise

The most elaborate description of Typhon is found in Nonnus’s Dionysiaca. Nonnus makes numerous references to Typhon’s serpentine nature,[7] giving him a “tangled army of snakes”,[8] snaky feet,[9] and hair.[10] According to Nonnus, Typhon was a “poison-spitting viper”,[11] whose “every hair belched viper-poison”,[12] and Typhon “spat out showers of poison from his throat; the mountain torrents were swollen, as the monster showered fountains from the viperish bristles of his high head”,[13] and “the water-snakes of the monster’s viperish feet crawl into the caverns underground, spitting poison!”.[14]

According to Hesiod’s Theogony, Typhon “was joined in love” to Echidna, a monstrous half-woman and half-snake, who bore Typhon “fierce offspring”.[16] First, according to Hesiod, there was Orthrus,[17] the two-headed dog who guarded the Cattle of Geryon, second Cerberus,[18] the multiheaded dog who guarded the gates of Hades, and third the Lernaean Hydra,[19] the many-headed serpent who, when one of its heads was cut off, grew two more. The Theogony next mentions an ambiguous “she”, which might refer to Echidna, as the mother of the Chimera (a fire-breathing beast that was part lion, part goat, and had a snake-headed tail) with Typhon then being the father.[20]

While mentioning Cerberus and “other monsters” as being the offspring of Echidna and Typhon, the mythographer Acusilaus (6th century BC) adds the Caucasian Eagle that ate the liver of Prometheus.[21]

The sea serpents which attacked the Trojan priest Laocoön, during the Trojan War, were perhaps supposed to be the progeny of Typhon and Echidna.[22] According to Hesiod, the defeated Typhon is the father of destructive storm winds.[23]

Typhon challenged Zeus for rule of the cosmos.[24] The earliest mention of Typhon, and his only occurrence in Homer, is a passing reference in the Iliad to Zeus striking the ground around where Typhon lies defeated.[25] Hesiod’s Theogony gives the first account of their battle. According to Hesiod, without the quick action of Zeus, Typhon would have “come to reign over mortals and immortals”.[26] In the Theogony Zeus and Typhon meet in cataclysmic conflict.

Zeus with his thunderbolt easily overcomes Typhon,[27] who is thrown down to earth in a fiery crash. Defeated, Typhon is cast into Tartarus by an angry Zeus.[28]

Most accounts have the defeated Typhon buried under either Mount Etna in Sicily, or the volcanic island of Ischia, the largest of the Phlegraean Islands off the coast of Naples, with Typhon being the cause of volcanic eruptions and earthquakes.

In addition to Typhon, other mythological beings were also said to be buried under Mount Etna and the cause of its volcanic activity.

Typhon’s name has a number of variants.[29] The earliest forms,Typhoeus and Typhaon, occur prior to the 5th century BC. Homer uses Typhoeus,[30] Hesiod and the Homeric Hymn to Apollo use both Typhoeus and Typhaon.[31] The later forms Typhos and Typhon occur from the 5th century BC onwards, with Typhon becoming the standard form by the end of that century.

Though several possible derivations of the name Typhon have been suggested, the derivation remains uncertain.[32] Consistent with Hesiod’s making storm winds Typhon’s offspring, some have supposed that Typhon was originally a wind-god, and ancient sources associated him with the Greek words tuphon, tuphos meaning “whirlwind”.[33] Other theories include derivation from a Greek root meaning “smoke” (consistent with Typhon’s identification with volcanoes),[34] from an Indo-European root (*dhuH-) meaning “abyss” (making Typhon a “Serpent of the Deep”),[35][36] and from Sapõn the Phoenician name for the Ugaritic god Baal’s holy mountain Jebel Aqra (the classical Mount Kasios) associated with the epithet Baʿal Sapōn.[37]

The name may have influenced the Persian word tūfān which is a source of the meteorological term typhoon.[38]

From apparently as early as Hecataeus of Miletus (c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC), Typhon was identified with Set, the Egyptian god of chaos and storms.[39]

Conclusion

Besides being the most powerful monster in Greek mythology and waging war on the Olympians, Typhon was famous for his offspring – the father of all monsters. It is a classic tale of the struggle between good and evil.

The archetypal figure of Typhon is subjectively interpreted by some as a symbol of ignorance. United with Echidna (who symbolizes the corruptions of the earth, rot, slime, fetid waters, illness and disease) their perverted force spawned a generation of great monsters: Orthros, Cerberus, the Lernaean Hydra and the Chimera which represent the lies, desire and illusion. Although defeated, the actions described in mythology indicate a consequence. The perpetual negative effect, stemming from his offspring.

Whether the ancients described virtue and morals, natural and climate events they observed or something else is subject to personal interpretation. The history behind this symbol and mythological figure is essential to come to an informed interpretation.

[1] Hesiod,Theogony 820–822. Apollodorus, 1.6.3, and Hyginus, Fabulae Preface also have Typhon as the offspring of Gaia and Tartarus. However, Hyginus, Fabulae 152 has Typhon as the offspring of Tartarus and Tartara, where, according to Fontenrose, p. 77, Tartara was "no doubt [Gaia] herself under a name which designates all that lies beneath the earth."

[2] Apollodorus, 1.6.3

[3] Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes 522–523; Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound 353; Nicander, apud Antoninus Liberalis 28; Virgil, Georgics 1. 278–279; Ovid, Metamorphoses 5.321–331; Manilius, Astronomica 2.874–875 (pp. 150, 153); Lucan, Pharsalia 4.593–595; Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.154–155 (I pp. 14–15)

[4] Homeric Hymn to Apollo 305–355; Fontenrose, p. 72; Gantz, p. 49. Stesichorus (c. 630 – 555 BC), it seems, also had Hera produce Typhon alone to "spite Zeus", see Fragment 239 (Campbell, pp. 166–167); West 1966, p. 380; but see Fontenrose, p. 72 n. 5

[5] As for Typhon being a bane to mortals, Gantz, p. 49, remarks on the strangeness of such a description for one who would challenge the gods.

[7] Ogden 2013a, p. 72

[8] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.187 (I pp. 16–17)

[6] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.173 (I pp. 16–17), 2.32 (I pp. 46–47)

[7] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.218 (I pp. 18–19)

[8] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.187 (I pp. 16–17)

[9] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.30, 36 (I pp. 46–47), 2.141 (I pp. 54–55)

[10] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.508–509 (I pp. 38–41)

[9] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.31–33 (I pp. 46–47)

[10] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.173 (I pp. 16–17), 2.32 (I pp. 46–47)

[11] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.218 (I pp. 18–19)

[12] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.508–509 (I pp. 38–41)

[13] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.31–33 (I pp. 46–47)

[14] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.141–142 (I pp. 54–55)

[15] Ogden 2013a, p. 69; Gantz, p. 50; LIMC Typhon 14

[16] Hesiod, Theogony 306–314. Compare with Lycophron, Alexandra 1351 ff. (pp. 606–607), which refers to Echidna as Typhon's spouse (δάμαρ).

[17] Apollodorus, Library 2.5.10 also has Orthrus as the offspring of Typhon and Echidna. Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica (or Fall of Troy) 6.249–262 (pp. 272–273) has Cerberus as the offspring of Typhon and Echidna, and Orthrus as his brother.

[18] Acusilaus, fr. 13 Fowler (Fowler 2000, p. 11; Freeman, p. 15 fragment 6), Hyginus, Fabulae Preface, 151, and Quintus Smyrnaeus, loc. cit., also have Cerberus as the offspring of Typhon and Echidna. Bacchylides, Ode 5.62, Sophocles, Women of Trachis 1097–1099, Callimachus, fragment 515 Pfeiffer (Trypanis, pp. 258–259), Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.500–501, 7.406–409, all have Cerberus as the offspring of Echidna, with no father named.

[19] Hyginus, Fabulae Preface, 30 (only Typhon is mentioned), 151 also has the Hydra and as the offspring of Echidna and Typhon.

[20] Hesiod, Theogony, 319. The referent of the "she" in line 319 is uncertain, see Gantz, p. 22; Clay, p. 159, with n. 34

[21] Acusilaus, fr. 13 Fowler (Fowler 2000, p. 11; Freeman, p. 15 fragment 6); Fowler 2013, p. 28; Gantz, p. 22; Ogden 2013a, pp. 149–150

[22] Hošek, p. 678; see Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica (or Fall of Troy) 12.449–453 (pp. 518–519), where they are called "fearful monsters of the deadly brood of Typhon".

[23] Hesiod, Theogony 869–880, which specifically excludes the winds Notus (South Wind), Boreas (North Wind) and Zephyr (West Wind) which he says are "a great blessing to men"; West 1966, p. 381; Gantz, p. 49; Ogden 2013a, p. 226.

[24] Fontenrose, pp. 70–76; West 1966, pp. 379–383; Lane Fox, pp. 283–301; Gantz, pp. 48–50; Ogden 2013a, pp. 73–80

[25] Homer, Iliad 2.780–784, a reference, apparently, not to their original battle but to an ongoing "lashing" by Zeus of Typhon where he lies buried, see Fontenrose, pp. 70–72; Ogden 2013a, p. 76

[27] Zeus' apparently easy victory over Typhon in Hesiod, in contrast to other accounts of the battle (see below), is consistent with, for example, what Fowler 2013, p. 27 calls "Hesiod's pervasive glorification of Zeus".

[29] Ogden 2013a, p. 152; Fontenrose, p. 70

[30] Homer, Iliad 2.782, 783

[31] Hesiod, Theogony 306 (Typhaon), 821 (Typhoeus), 869 (Typhoeus); Homeric Hymn to Apollo 306 (Typhaon), 352 (Typhaon), 367 (Typhoeus)

[32] Fontenrose, p. 546; West 1966, p. 381; Lane Fox, 298, p. 405, p. 407 n. 53; Ogden 2013a, pp. 152–153. Fontenrose: "His name is very likely not Greek; but though non-Hellenic etymologies have been suggested, I doubt that its meaning is now recoverable"; West: "The origin of the name and its variant forms is unexplained"; Lane Fox: "a name of uncertain derivation". Given that Typhoeus and Typhaon are apparently the earlier forms, Ogden, suggests that theories based upon the assumption that "Typhon" is the primary form "seem ill-founded", and says that it "seems much more likely" that the form Typhon arose from "the desire to assimilate this drakōn's name to the name shape of other drakontes, perhaps Python in particular".

[33] West 1966, pp. 252, 381; Ogden 2013a, p. 152, both citing Worms 1953. But according to West "it is far from certain that there is any real etymological connection ... [Typhon's] association with the tornado is secondary, and due to popular etymology. It may have already influenced Hesiod, for there is at present no better explanation of the fact that irregular stormwinds (especially those met at sea) are made the children of [Typhon]." For the use of the words τῡφώς, τῡφῶν meaning "whirlwind" see LSJ, Τυ_φώς , ῶ, ὁ; Suda s.v. Tetuphômai, Tuphôn, Tuphôs; Aeschylus, Agamemnon 656; Aristophanes, Frogs 848, Lysistrata, 974; Sophocles, Antigone 418

[34] Fontenrose, p. 546 with n. 2; Lane Fox, p. 298, which offers the derivation of Typhon from the Greek τῡφῶν tūphōn ("smoking", "smouldering"), though Ogden 2013a, p. 153, while conceding that such a derivation "fits Typhon's nature and condition in life and death so perfectly", objects (n. 23) "why would the participle-style declension in –ων, –οντος have been substituted with one in –ῶν, –ῶνος?"

[35] Watkins, pp. 460–463; Ogden 2013a, pp. 152–153

[36] R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1522.

[37] Supported, with caveats, by West 1997, p. 303: "Here, then, we have a divinity [Baʿal Zaphon] with a name which might indeed have become "Typhon" in Greek", but rejected by Lane Fox, p. 298. See also Fontenrose, p. 546 n. 2; West 1966, p. 252; Ogden 2013a, p. 153, with n. 22.

[38] The Arabic Contributions to the English Language: An Historical Dictionary by Garland Hampton Cannon and Alan S. Kaye considers typhoon "a special case, transmitted by Cantonese, from Arabic, but ultimately deriving from Greek. [...] The Chinese applied the [Greek] concept to a rather different wind [...]"

[40] Fowler 2013, p. 28; Ogden 2013a, p. 78; West 1997, p. 304; West 1966, p. 380; Fontenrose, p. 177 ff.; Hecataeus FGrH 1 F300 (apud Herodotus, 2.144.2).

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.