Borromean Rings

Borromean Rings

Overview

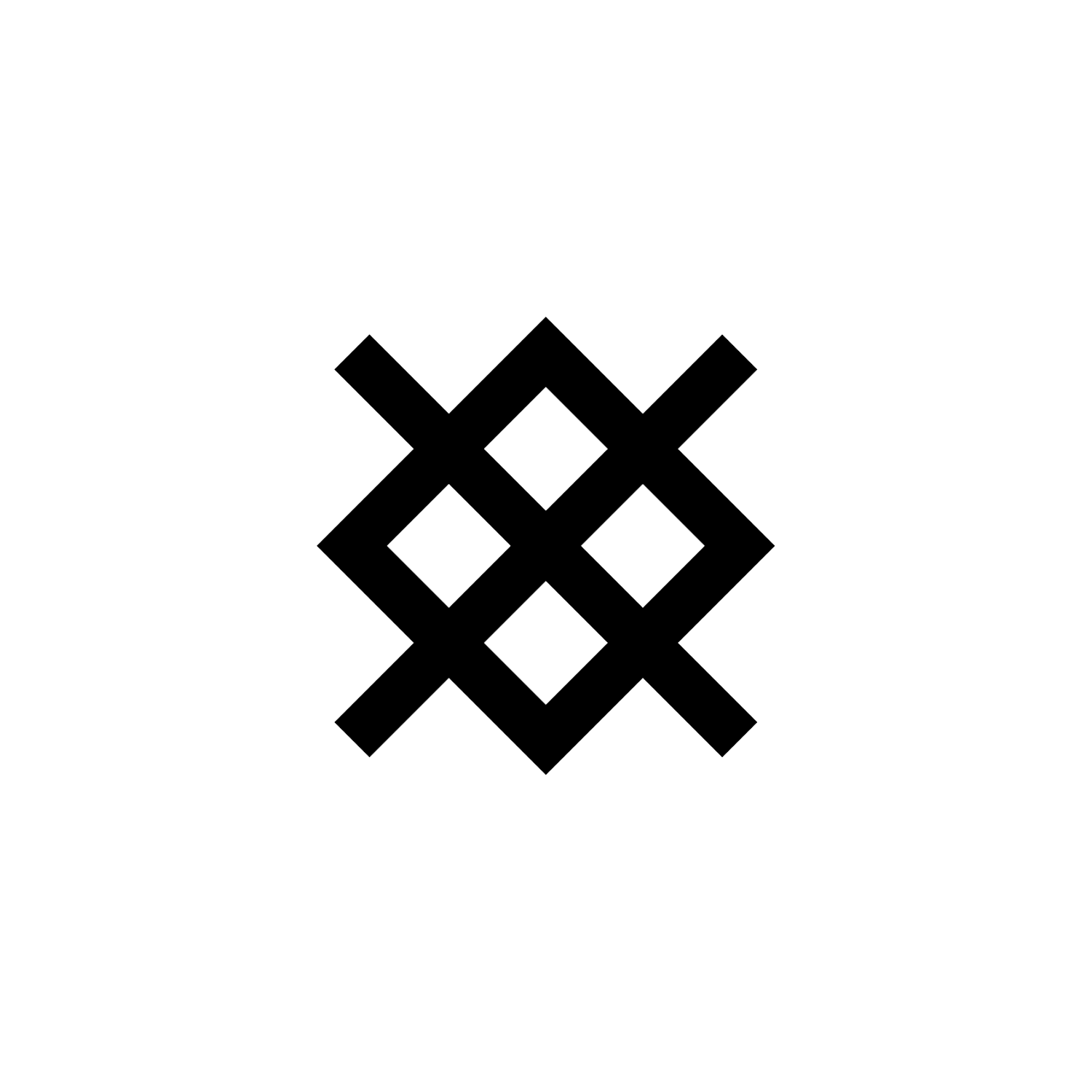

Borromean Rings, a renowned knot in the shape of three interlinked circles, have long served as an emblem of unity and interconnectedness, a metaphorical representation of the strength of collective entities. Their unique geometric properties are such that the removal of any one circle results in the remaining two falling apart, which makes them a potent symbol of interdependence and unity.

This symbolic representation has seen the Borromean Rings used in myriad contexts, from religious symbolism to scientific analogies, tracing back to antiquity.

Origin and Meaning

The name “Borromean rings” comes from the use of these rings, in the form of three linked circles, in the coat of arms of the aristocratic Borromeo family in Northern Italy.[1][2] The link itself is much older and has appeared in the form of the valknut, three linked equilateral triangles with parallel sides, on Norse image stones dating back to the 7th century.[3]

The Ōmiwa Shrine in Japan is also decorated with a motif of the Borromean rings, in their conventional circular form.[4] A stone pillar in the 6th-century Marundeeswarar Temple in India shows three equilateral triangles rotated from each other to form a regular enneagram; like the Borromean rings these three triangles are linked and not pairwise linked,[5] but this crossing pattern describes a different link than the Borromean rings.[6]

The Borromean rings have been used in different contexts to indicate strength in unity.[7] In particular, some have used the design to symbolize the Trinity.[8] A 13th-century French manuscript depicting the Borromean rings labeled as unity in trinity was lost in a fire in the 1940s, but reproduced in an 1843 book by Adolphe Napoléon Didron.

Didron and others have speculated that the description of the Trinity as three equal circles in canto 33 of Dante’s Paradiso was inspired by similar images, although Dante does not detail the geometric arrangement of these circles.[9][10]

Dante comes face to face with God in Cantos XXXII and XXXIII. God appears as three equally large circles occupying the same space, representing the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Within these circles Dante can discern the human form of Christ.

The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan found inspiration in the Borromean rings as a model for his topology of human subjectivity, with each ring representing a fundamental Lacanian component of reality (the “real”, the “imaginary”, and the “symbolic”).[11]

The first work of knot theory to include the Borromean rings was a catalog of knots and links compiled in 1876 by Peter Tait.[12]

In recreational mathematics, the Borromean rings were popularized by Martin Gardner, who featured Seifert surfaces for the Borromean rings in his September 1961 “Mathematical Games” column in Scientific American.[13]

In medieval and renaissance Europe, a number of visual signs consist of three elements interlaced together in the same way that the Borromean rings are shown interlaced (in their conventional two-dimensional depiction), but with individual elements that are not closed loops. Examples of such symbols are the Snoldelev stone horns[14] and the Diana of Poitiers crescents.[15]

Some knot-theoretic links contain multiple Borromean rings configurations; one five-loop link of this type is used as a symbol in Discordianism, based on a depiction in the Principia Discordia.[16]

The Medici

The figure of the three entwined rings can be found as a marble inlay on the Rucellai tomb in the

‘Tempietto del Santo Sepolcro’ (built 1457-67 in Florence).

The author of the first Italian treatise on Imprese, Paolo Giovio (1483-1552), posthumously attributed the three diamond rings to Cosimo il Vecchio in his ‘Dialogo dell’imprese’ in 1551.

In fact, the Medici preferred variations of just one diamond ring combined with the motto SEMPER later in the 15th century.

Cosimo de Medici (1389-1464) used this symbol of three rings interlaced in the Borromean fashion. The church also found it a useful way to illustrate the intellectually obscure conjunction of monotheism and the concept of the Trinity.

Conclusion

The meaning of Borromean rings is that as a threesome they cannot be separated, but if you take away any one ring the remaining two are not joined.

As a symbol it has been named after the Borromeo family in Northern Italy, but it predates its association with the family by centuries.

It has been seen in temples and shrines in Asia, and could possibly be what Dante saw when he described his face to face encounter with God in Canto 33 of Paradiso.

[1] Crum Brown, Alexander (December 1885), "On a case of interlacing surfaces", Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 13: 382–386

[2] Schoeck, Richard J. (Spring 1968), "Mathematics and the languages of literary criticism", The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 26 (3): 367–376, doi:10.2307/429121, JSTOR 429121

[3] Bruns, Carson J.; Stoddart, J. Fraser (2011), "The mechanical bond: A work of art", in Fabbrizzi, L. (ed.), Beauty in Chemistry, Topics in Current Chemistry, vol. 323, Springer, pp. 19–72, doi:10.1007/128_2011_296, PMID 22183145

[4] Gunn, Charles; Sullivan, John M. (2008), "The Borromean Rings: A video about the New IMU logo", in Sarhangi, Reza; Séquin, Carlo H. (eds.), Bridges Leeuwarden: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture, London: Tarquin Publications, pp. 63–70, ISBN 978-0-9665201-9-4; see the video itself at "The Borromean Rings: A new logo for the IMU Archived 2021-03-08 at the Wayback Machine" [w/video], International Mathematical Union

[5] Lakshminarayan, Arul (May 2007), "Borromean triangles and prime knots in an ancient temple", Resonance, 12 (5): 41–47, doi:10.1007/s12045-007-0049-7, S2CID 120259064

[6] Jablan, Slavik V. (1999), "Are Borromean links so rare?", Proceedings of the 2nd International Katachi U Symmetry Symposium, Part 1 (Tsukuba, 1999), Forma, 14 (4): 269–277, MR 1770213

[7] Aravind, P. K. (1997), "Borromean entanglement of the GHZ state" (PDF), in Cohen, R. S.; Horne, M.; Stachel, J. (eds.), Potentiality, Entanglement and Passion-at-a-Distance, Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Springer, pp. 53–59, doi:10.1007/978-94-017-2732-7_4, MR 1739812

[8] Cromwell, Peter; Beltrami, Elisabetta; Rampichini, Marta (March 1998), "The Borromean rings", The mathematical tourist, The Mathematical Intelligencer, 20 (1): 53–62, doi:10.1007/bf03024401, S2CID 189888135

[9] Didron, Adolphe Napoléon (1843), Iconographie Chrétienne (in French), Paris: Imprimerie Royale, pp. 568–569

[10] Saiber, Arielle; Mbirika, aBa (2013), "The Three Giri of Paradiso 33" (PDF), Dante Studies (131): 237–272, JSTOR 43490498

[11] Ragland-Sullivan, Ellie; Milovanovic, Dragan (2004), "Introduction: Topologically Speaking", Lacan: Topologically Speaking, Other Press, ISBN 978-1-892746-76-4

[12] Cromwell, Peter; Beltrami, Elisabetta; Rampichini, Marta (March 1998), "The Borromean rings", The mathematical tourist, The Mathematical Intelligencer, 20 (1): 53–62, doi:10.1007/bf03024401, S2CID 189888135

[13] Gardner, Martin (September 1961), "Surfaces with edges linked in the same way as the three rings of a well-known design", Mathematical Games, Scientific American, reprinted as Gardner, Martin (1991), "Knots and Borromean Rings", The Unexpected Hanging and Other Mathematical Diversions, University of Chicago Press, pp. 24–33; see also Gardner, Martin (September 1978), "The Toroids of Dr. Klonefake", Asimov's Science Fiction, vol. 2, no. 5, p. 29

[14] Baird, Joseph L. (1970), "Unferth the þyle", Medium Ævum, 39 (1): 1–12, doi:10.2307/43631234, JSTOR 43631234, the stone bears also representations of three horns interlaced

[15] Cromwell, Peter; Beltrami, Elisabetta; Rampichini, Marta (March 1998), "The Borromean rings", The mathematical tourist, The Mathematical Intelligencer, 20 (1): 53–62, doi:10.1007/bf03024401, S2CID 189888135

[16] "Mandala", Principia Discordia (4th ed.), March 1970, p. 43

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.