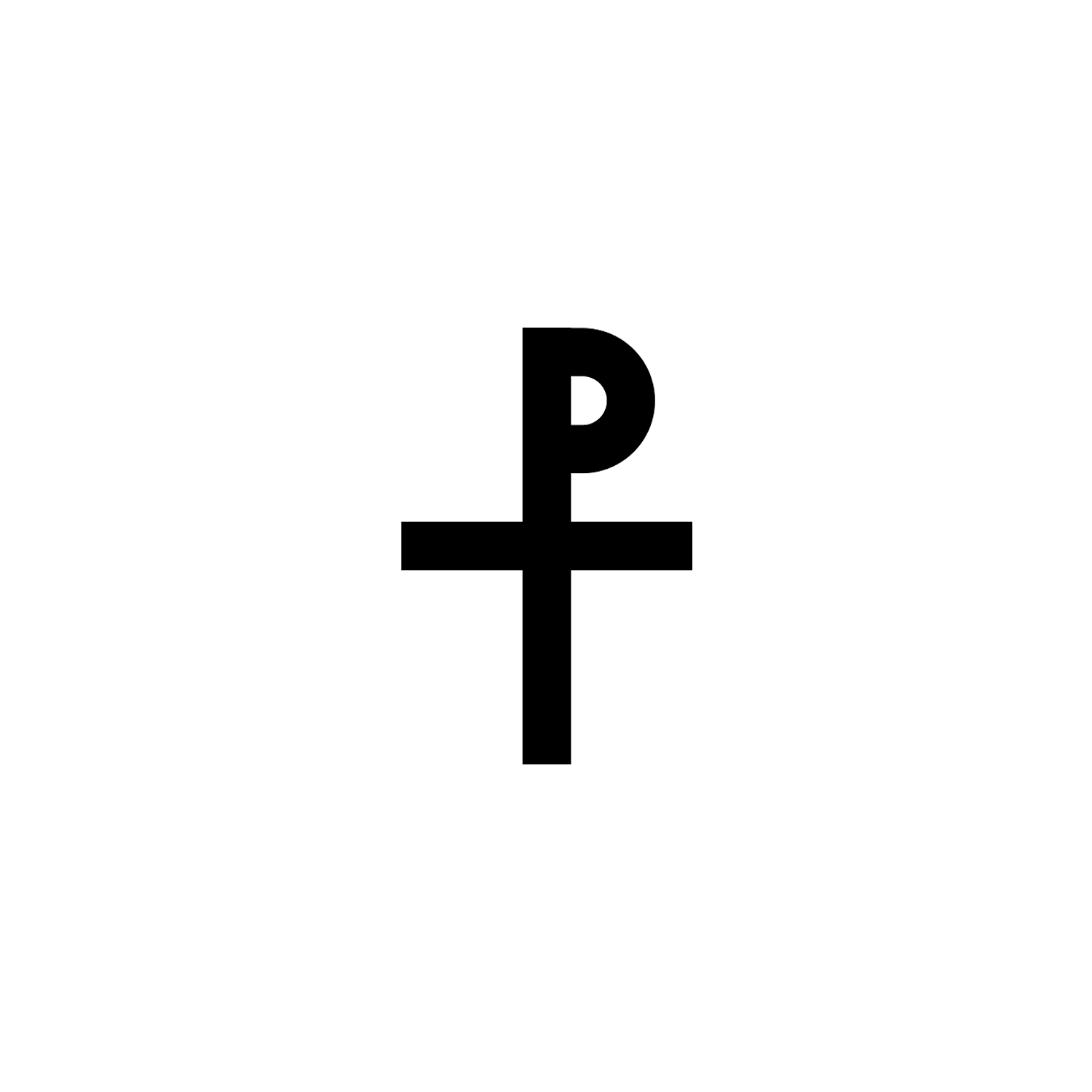

Chi Ro

Chi Ro

Also referred to as the Labarum and Chrismon.

Overview

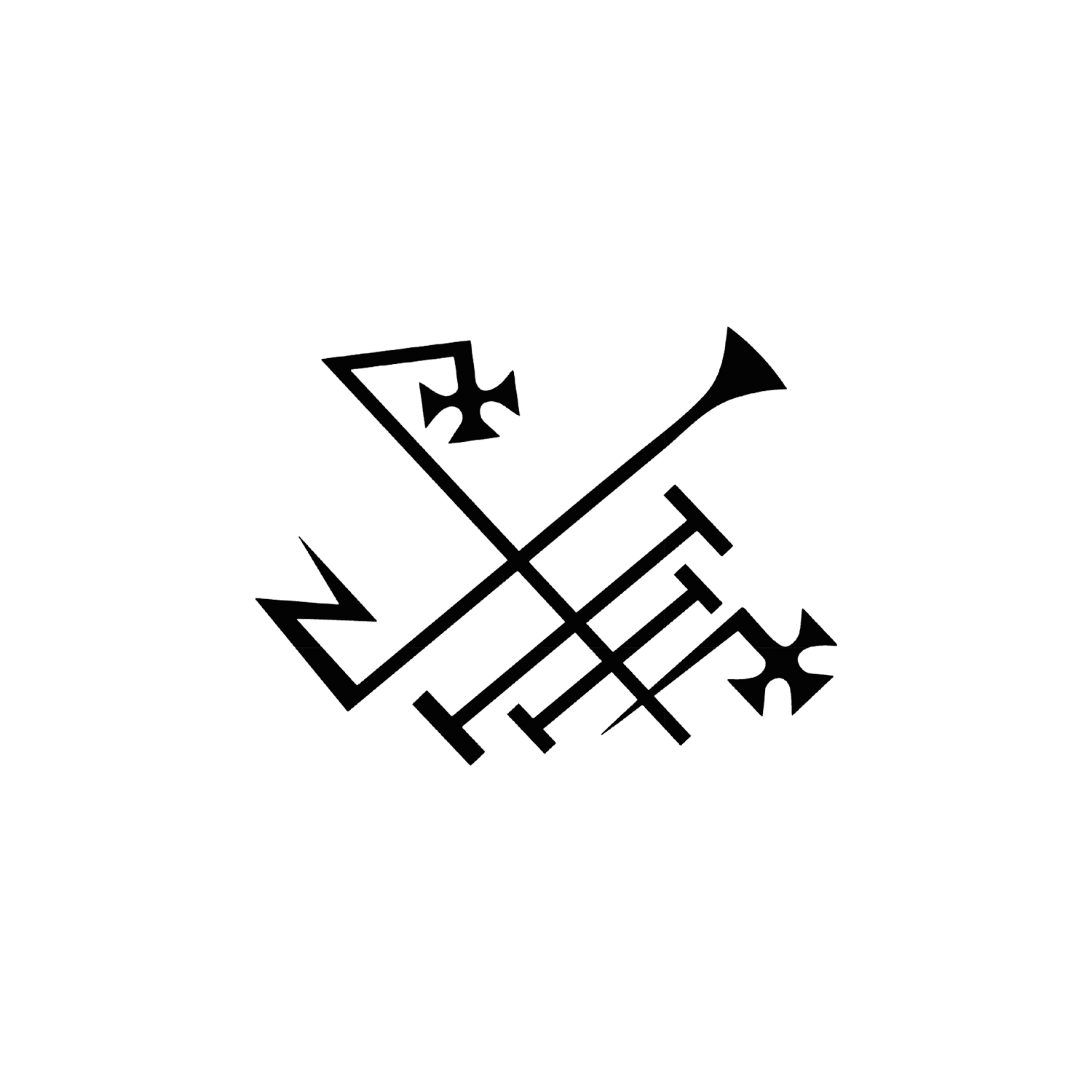

The Chi Rho (☧, English pronunciation /ˈkaɪ ˈroʊ/; also known as chrismon[1]) is one of the earliest forms of the Christogram, formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters—chi and rho (ΧΡ)—of the Greek word ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Christos) in such a way that the vertical stroke of the rho intersects the center of the chi.[2]

The Chi-Rho symbol was used by the Roman Emperor Constantine I (r. 306–337 AD) as part of a military standard (vexillum). Constantine’s standard was known as the Labarum. Early symbols similar to the Chi Rho were the Staurogram and the IX monogram.

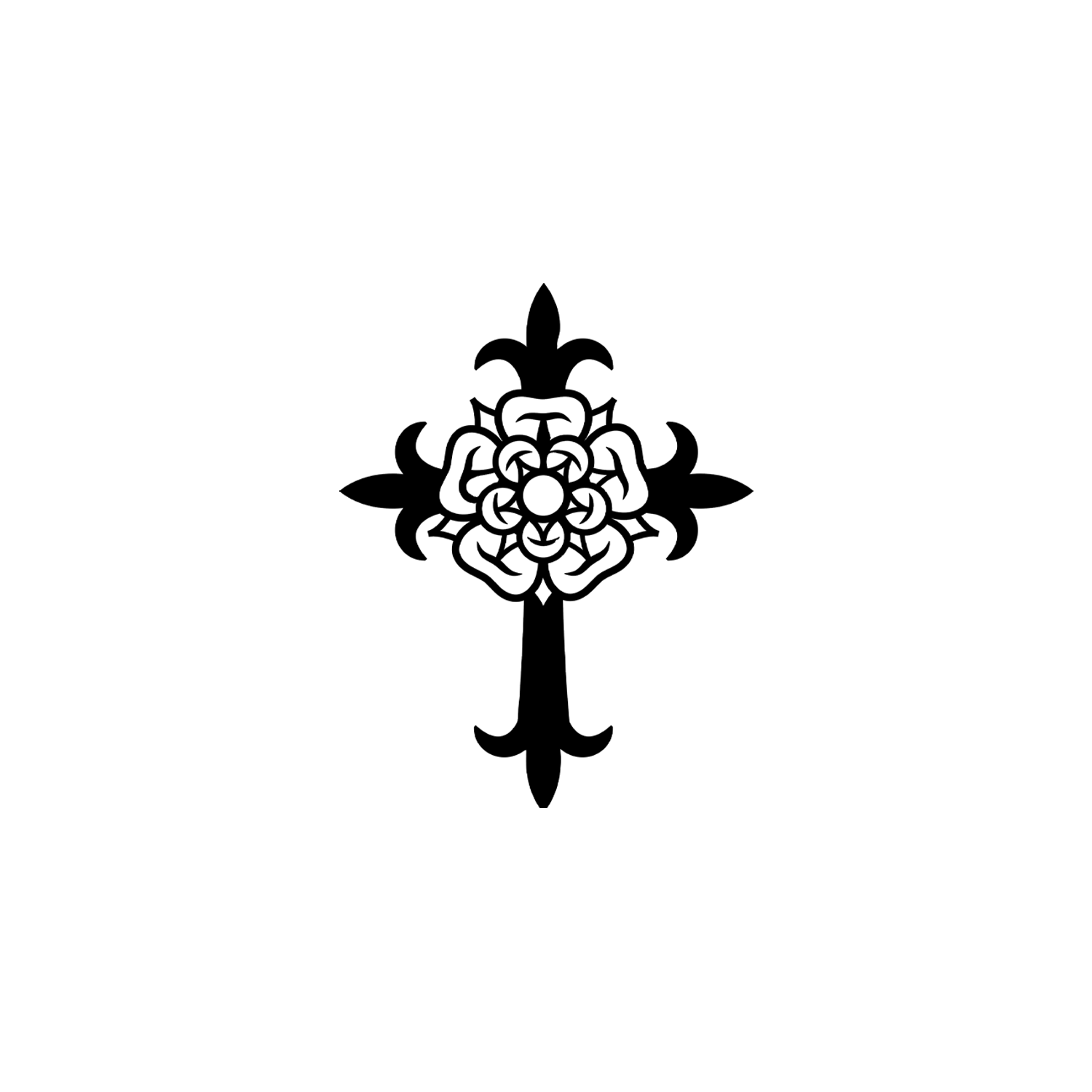

In time christograms came to be used not only in texts but as free-standing symbols of Christ or Christian faith, for example on liturgical vestments and church utensils.

In antiquity, the cross, i.e. the instrument of Christ’s crucifixion (crux, stauros), was taken to be T-shaped, while the X-shape (chi) had different connotations.

The most commonly encountered Christogram in English-speaking countries in modern times is the Χ (or more accurately, Chi), representing the first letter of the word Christ, in such abbreviations as Xmas (for “Christmas”) and Xian or Xtian (for “Christian”).

The Alpha and Omega symbols may at times accompany the Chi-Rho monogram. Since the 17th century, Chrismon (chrismum; also chrismos, chrismus) has been used as a Neo-Latin term for the Chi Rho monogram.

Origin and Meaning

In pre-Christian times, the Chi-Rho symbol was also used to mark a particularly valuable or relevant passage in the margin of a page, abbreviating chrēston (good).[3] Some coins of Ptolemy III Euergetes (r. 246–222 BC) were marked with a Chi-Rho.[4]

Although formed of Greek characters, the device (or its separate parts) is frequently found serving as an abbreviation in Latin text, with endings added appropriate to a Latin noun, thus XPo, signifying Christo, “to Christ”, the dative form of Christus,[5] or χρ̅icola, signifying Christicola, “Christian”, in the Latin lyrics of Sumer is icumen in.

According to Lactantius,[6] a Latin historian of North African origins saved from poverty by the Emperor Constantine the Great (r. 306–337), who made him tutor to his son Crispus, Constantine had dreamt of being ordered to put a “heavenly divine symbol” (Latin: coeleste signum dei) on the shields of his soldiers.

The description of the actual symbol chosen by Emperor Constantine the next morning, as reported by Lactantius, is not very clear: it closely resembles a Tau-Rho or a staurogram, a similar Christian symbol. That very day Constantine’s army fought the forces of Maxentius and won the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312), outside Rome.

Eusebius of Caesarea (died in 339) gave two different accounts of the events. In his church history, written shortly after the battle, when Eusebius had not yet had contact with Constantine, he does not mention any dream or vision, but compares the defeat of Maxentius (drowned in the Tiber) to that of the biblical pharaoh and credits Constantine’s victory to divine protection.

In a memoir of the Roman emperor that Eusebius wrote after Constantine’s death (On the Life of Constantine, c. 337–339), a miraculous appearance is said to have come in Gaul long before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. In this later version, the Roman emperor had been pondering the misfortunes that befell commanders who invoked the help of many different gods, and decided to seek divine aid in the forthcoming battle from the One God. At noon, Constantine saw a cross of light imposed over the sun.

Attached to it, in Greek characters, was the saying “Ev tούτῳ Νίκα!” (“In this, conquer!”).[7] Not only Constantine, but the whole army saw the miracle. That night, Christ appeared to the Roman emperor in a dream and told him to make a replica of the sign he had seen in the sky, which would be a sure defence in battle.

Eusebius wrote in the Vita that Constantine himself had told him this story “and confirmed it with oaths” late in life “when I was deemed worthy of his acquaintance and company.” “Indeed”, says Eusebius, “had anyone else told this story, it would not have been easy to accept it.”

Eusebius also left a description of the labarum, the military standard which incorporated the Chi-Rho sign, used by Emperor Constantine in his later wars against Licinius.[8]

Ancient sources draw an unambiguous distinction between the two terms “labarum” and “Chi-Rho”, even though later usage sometimes regards the two as synonyms. The name labarum was applied both to the original standard used by Constantine the Great and to the many standards produced in imitation of it in the Late Antique world, and subsequently.

The labarum does not appear on any of several standards depicted on the Arch of Constantine, which was erected just three years after the battle. If Eusebius’ oath-confirmed account of Constantine’s vision and the role it played in his victory and conversion can be trusted, then a grand opportunity for the kind of political propaganda that the Arch was built to present was missed.

Many historians have argued that in the early years after the battle, the Emperor had not yet decided to give clear public support to Christianity, whether from a lack of personal faith or because of fear of religious friction.

The arch’s inscription does say that the Emperor had saved the res publica INSTINCTV DIVINITATIS MENTIS MAGNITVDINE (“by greatness of mind and by instinct [or impulse] of divinity”). Continuing the iconography of his predecessors, Constantine’s coinage at the time was inscribed with solar symbolism, interpreted as representing Sol Invictus (the Unconquered Sun), Helios, Apollo, or Mithras, but in 325 and thereafter the coinage ceases to be explicitly pagan, and Sol Invictus disappears.

And although Eusebius’ Historia Ecclesiae further reports that Constantine had a statue of himself “holding the sign of the Savior [the cross] in his right hand” erected after his victorious entry into Rome, there are no other reports to confirm such a monument.

Historians still dispute whether Constantine was the first Christian Emperor to support a peaceful transition to Christianity during his rule, or an undecided pagan believer until middle age, and also how strongly influenced he was in his political-religious decisions by his Christian mother St. Helena.

As for the labarum itself, there is little evidence for its use before 317.[9] In the course of Constantine’s second war against Licinius in 324, the latter developed a superstitious dread of Constantine’s standard. During the attack of Constantine’s troops at the Battle of Adrianople the guard of the labarum standard were directed to move it to any part of the field where his soldiers seemed to be faltering.

The appearance of this talismanic object appeared to embolden Constantine’s troops and dismay those of Licinius.[10] At the final battle of the war, the Battle of Chrysopolis, Licinius, though prominently displaying the images of Rome’s pagan pantheon on his own battle line, forbade his troops from actively attacking the labarum, or even looking at it directly.[11]

Constantine felt that both Licinius and Arius were agents of Satan, and associated them with the serpent described in the Book of Revelation (12:9).[12] Constantine represented Licinius as a snake on his coins.[13]

Eusebius stated that in addition to the singular labarum of Constantine, other similar standards (labara) were issued to the Roman army. This is confirmed by the two labara depicted being held by a soldier on a coin of Vetranio (illustrated above) dating from 350.

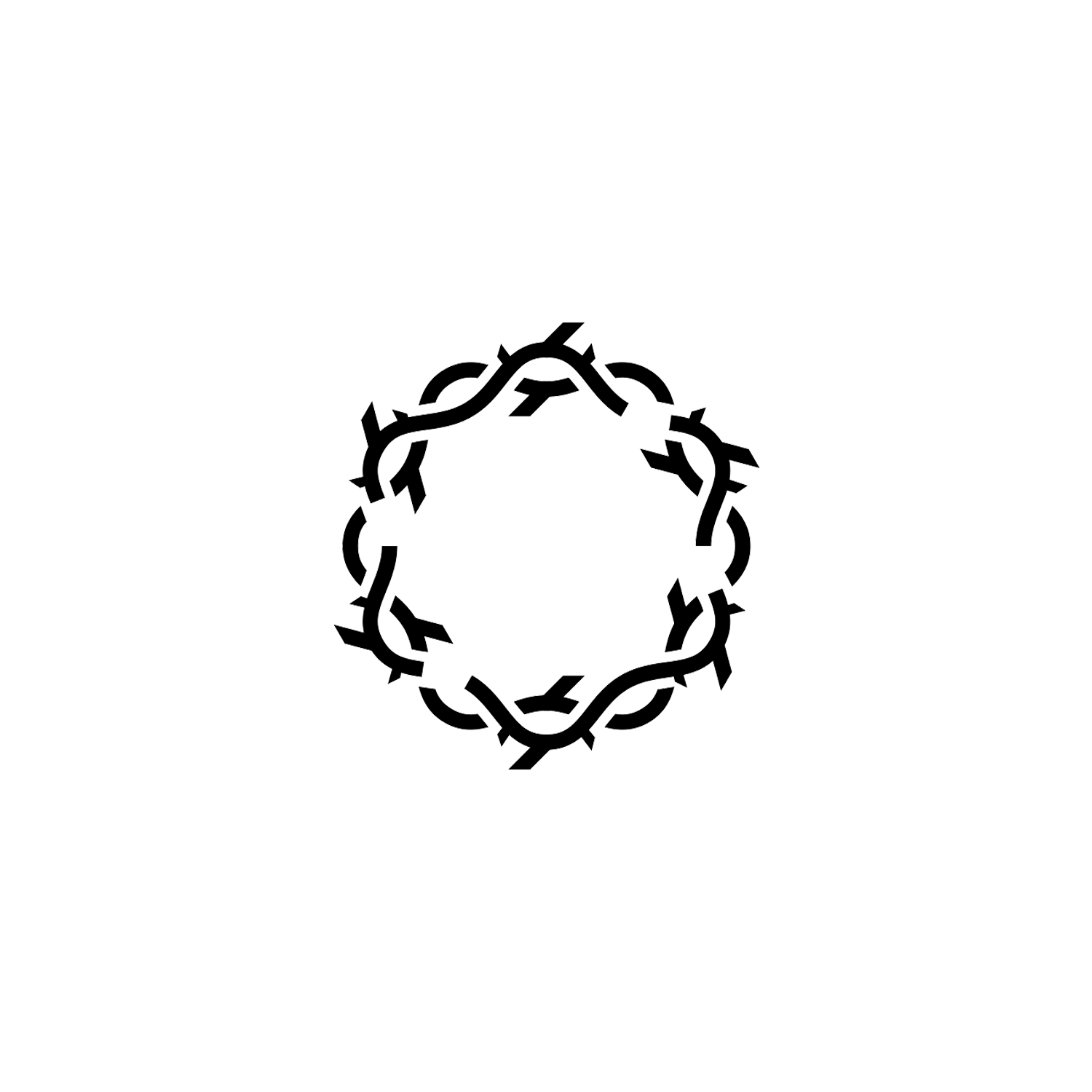

An early visual representation of the connection between the Crucifixion of Jesus and his resurrection, seen in the 4th century sarcophagus of Domitilla in Rome, the use of a wreath around the Chi-Rho symbolizes the victory of the Resurrection over death.[14]

After Constantine, the Chi-Rho became part of the official imperial insignia. Archaeologists have uncovered evidence demonstrating that the Chi-Rho was emblazoned on the helmets of some Late Roman soldiers. Coins and medallions minted during Emperor Constantine’s reign also bore the Chi-Rho. By the year 350, the Chi-Rho began to be used on Christian sarcophagi and frescoes.

A miniature version of the labarum became part of the imperial regalia of Byzantine rulers, who were often depicted carrying it in their right hands.

A Romano-British Chi-Rho, in fresco, was found at the site of a villa at Lullingstone (illustrated). The symbol was also found on Late Roman Christian signet rings in Britain.[15]

In 2020, archaeologists discovered in Vindolanda in northern England a 5th-century chalice covered in religious iconography, including the Chi-Rho.[16][17]

A later Byzantine manuscript indicates that a jewelled labarum standard believed to have been that of Constantine was preserved for centuries, as an object of great veneration, in the imperial treasury at Constantinople.[18] The labarum, with minor variations in its form, was widely used by the Christian Roman emperors who followed Constantine.

The term “labarum” can be generally applied to any ecclesiastical banner, such as those carried in religious processions.

“The Holy Lavaro” were a set of early national Greek flags, blessed by the Greek Orthodox Church. Under these banners the Greeks united throughout the Greek Revolution (1821), a war of liberation waged against the Ottoman Empire.

Labarum also gives its name (Labaro) to a suburb of Rome adjacent to Prima Porta, one of the sites where the ‘Vision of Constantine’ is placed by tradition.

Insular Gospel books

In Insular Gospel books, the beginning of Matthew 1:18, at the end of his account of the genealogy of Christ and introducing his account of the life, so representing the moment of the Incarnation of Christ, was usually marked with a heavily decorated page, where the letters of the first word “Christi” are abbreviated and written in Greek as “XPI”, and often almost submerged by decoration.[19]

Though the letters are written one after the other and the “X” and “P” not combined in a monogram, these are known as Chi-Rho pages.

Conclusion

The Chi Rho, or Labarum, is a central Christogram with origins in the earliest years of Roman Christianity.

On the evening of October 27, 312 AD, with his army preparing for the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, the emperor Constantine I claimed to have had a vision, which led him to believe he was fighting under the protection of the Christian God.

Two of the main accounts of the battle, both by Eusebius of Caesarea, contradict each other on the apparition of the symbol. Either way Constantine made extensive use of the Chi-Rho and the labarum later in the conflict with Licinius.

It is uncertain if Constantine was a Christian at the time of the battle or if he became one later in life.

Just before his death in May 337, it is claimed that Constantine was baptised into Christianity. Up until this time he had been a catechumen for most of his adult life. He believed that if he waited to get baptized on his death bed he was in less danger of polluting his soul with sin and not getting to heaven.

It is possible (but not certain) that Constantine’s mother, Helena, exposed him to Christianity; in any case he only declared himself a Christian after issuing the Edict of Milan.

The symbol is very similar to the Staurogram.

[1] From a supposed Middle Latin crismon), specifically applied to the "Chrismon of Saint Ambrose" in Milan Cathedral. Crismon (par les Bénédictins de St. Maur, 1733–1736), in: du Cange, et al., Glossarium mediae et infimae latinitatis, ed. augm., Niort: L. Favre, 1883‑1887, t. 2, col. 621b. "CRISMON, Nota quæ in libro ex voluntate uniuscujusque ad aliquid notandum ponitur. Papias in MS. Bituric. Crismon vel Chrismon proprie est Monogramma Christi sic expressum ☧"; 1 chrismon (par les Bénédictins de St. Maur, 1733–1736), in: du Cange, et al., Glossarium mediae et infimae latinitatis, ed. augm., Niort : L. Favre, 1883‑1887, t. 2, col. 318c Archived 2016-08-26 at the Wayback Machine.

[2] Steffler, Alva William (2002). Symbols of the Christian Faith. p. 66. Grand Rapids, Michigan and Cambridge, United Kingdom: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-4676-9.

[3] Southern 2001, p. 281; Grant 1998, p. 142, citing Bruun, Studies in Constantinian Numismatics.

[4] von Reden 2007, p. 69: "The chi-rho series of Euergetes' reign had been the most extensive series of bronze coins ever minted, comprising eight denominations from 1 chalkous to 4 obols."

[5] For example as inscribed on the monumental brass of Thomas de Camoys, 1st Baron Camoys (d.1421) in St George's Church, Trotton, Sussex, England

[6] Lactantius. On the Deaths of the Persecutors, Chapter 44.

[7] The well known sentence In hoc signo vinces is simply a later Latin translation of Eusebius's Greek wording.

[8] Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine, Chapter 31.

[9] Smith, JH, p. 104: "What little evidence exists suggests that in fact the labarum bearing the chi-rho symbol was not used before 317, when Crispus became Caesar..."

[10] Odahl, Charles Matson. Constantine and the Christian empire. p. 178. 2004 ISBN 0-415-17485-6

[11] Odahl, Charles Matson. Constantine and the Christian empire. p. 180. 2004 ISBN 0-415-17485-6

[12] Constantine and the Christian empire by Charles Matson Odahl 2004 ISBN 0-415-17485-6 page 315

[13] A Companion to Roman Religion edited by Jörg Rüpke 2011 ISBN 1-4443-3924-9 page 159

[14] Harries 2004, p. 8. Sarcophagus with Scenes of the Passion (probably from the Catacomb of Domitilla), Rome, mid-fourth century. Marble, 23ʺ x 80ʺ. Museo Pio Christiano, Vatican, Rome.

[15] Johns, Catherine (1996). The Jewellery of Roman Britain: Celtic and classical Traditions. p. 67. Oxon, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group). ISBN 1-85728-566-2.

[16] "Hadrian's Wall dig reveals oldest Christian graffiti on chalice". theguardian. 29 August 2020.

[17] "Early Christian Chalice Unearthed in Northern England". archaeology.org. 31 August 2020.

[18] Lieu and Montserrat p. 118. From a Byzantine life of Constantine (BHG 364) written in the mid to late ninth century.

[19] In the Latin Vulgate the verse was "Christi autem generatio sic erat cum esset desponsata mater eius Maria Ioseph antequam convenirent inventa est in utero habens de Spiritu Sancto" ("Now the birth of Jesus Christ took place in this way. When his mother Mary had been betrothed to Joseph, before they came together she was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit")

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.