Triple Goddess

Triple Goddess

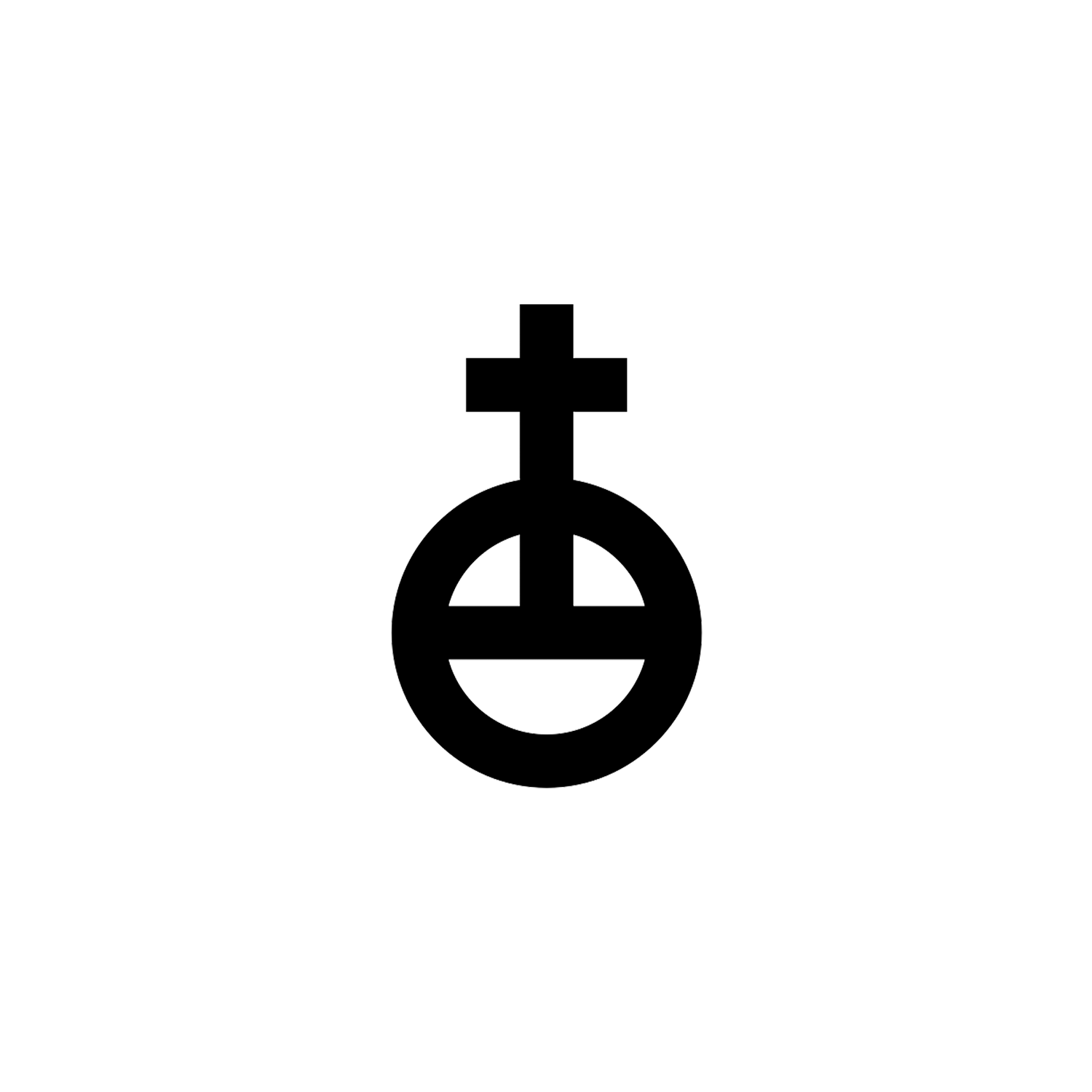

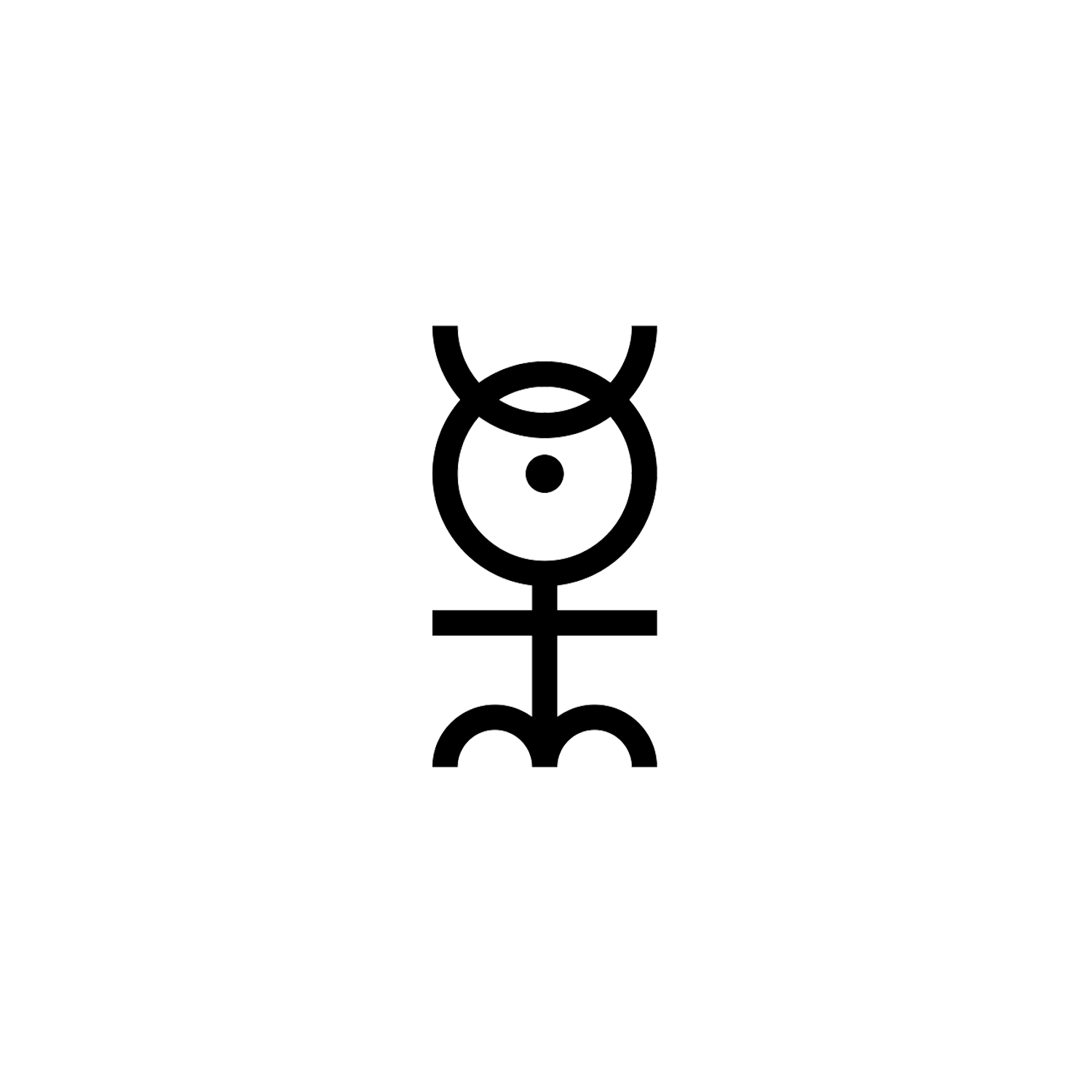

Waxing, Full and Crescent moon.

Overview

The Triple Goddess is one of the two primary deities found in Wicca and some related forms of Neopaganism, it is also a concept applied to Diana, a goddess in Roman and Hellenistic religion, or Hecate

Certain Wiccan traditions are Goddess-centric; this view differs from most traditions in that most others focus on a duality of a Triple Goddess and a Horned God. The Triple Goddess is a deity or deity archetype revered in many Neopagan religious and spiritual traditions. In common Neopagan usage, the Triple Goddess is viewed as a triunity of three distinct aspects or figures united in one being.

These three figures are often described as the Maiden, the Mother, and the Crone, each of which symbolizes both a separate stage in the female life cycle and a phase of the Moon, and often rules one of the realms of heavens, earth, and underworld. In various forms of Wicca, her masculine consort is the Horned God.

The symbol of the Triple Goddess is that of the waxing, full and crescent moon stages in that order.

Origin and Meaning

Various triune or triple goddesses, or deities who appeared in groupings of three, were known to ancient religion. Well-known examples include the Tridevi (Saraswati, Lakshmi, and Parvati), Triglav (Slavs), the Charites (Graces), the Horae (Seasons, of which there were three in the ancient Hellenistic reckoning), and the Moirai (Fates).

Some deities generally depicted as singular also included triplicate aspects. In Stymphalos, Hera was worshiped as a Girl, a Grown-up, and a Widow.[1]

According to Robert Graves, Hecate was the “original” and most predominant ancient triple moon goddess. Hecate was represented in triple form from the early days of her worship.

In the ancient, medieval, and modern periods, Diana has been considered a triple deity, merged with a goddess of the moon (Luna/Selene) and the underworld (usually Hecate).[2][3]

Diana (Artemis) also came to be viewed as a trinity of three goddesses in one, which were viewed as distinct aspects of a single divine being: “Diana as huntress, Diana as the moon, Diana of the underworld.”[4] Additional examples of the goddess Hecate viewed as a triple goddess associated with witchcraft include Lucan’s tale of a group of witches, written in the 1st century BCE.

In Lucan’s work (LUC. B.C. 6:700-01), the witches speak of “Persephone, who is the third and lowest aspect of our goddess Hecate”.[5] Another example is found in Ovid’s Metamorphosis (Met. 7:94–95), in which Jason swears an oath to the witch Medea, saying he would “be true by the sacred rites of the three-fold goddess.”[6]

The specific character of the modern neopagan Maiden, Mother, and Crone archetype is not found in any ancient sources related directly to Hecate.[7] Both Diana and Hecate were almost invariably described as maiden goddesses, with an appearance like that of a young woman.[8]

However, according to the 3rd century BC grammarian Epigenes, the three Moirai, or Fates, were regarded by the Orphic tradition as representing the three divisions of the Moon, “the thirtieth and the fifteenth and the first” (i.e. the crescent moon, full moon, and dark moon, as delinted by the divisions of the calendar month).[9] The Moirai themselves are traditionally depicted as a young girl, or Spinner of the thread of life, an older woman, or Measurer, and an elderly woman, or Cutter, representing birth, active life, and death.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the Moirai, often known in English as the Fates—were the personifications of destiny. They were three sisters: Clotho (the spinner), Lachesis (the allotter), and Atropos (the inevitable, a metaphor for death).

The connection between the Fates and the variously named Triple Moon Goddess, then ultimately led to the conflation of these concepts.[10] Servius made the explicit connection between these phases and the roles of the Moirai: “some call the same goddess Lucina, Diana, and Hecate, because they assign to one goddess the three powers of birth, growth, and death.

Some that say that Lucina is the goddess of birth, Diana of growth, and Hecate of death. On account of this three-fold power, they have imagined her as three-fold and three-form, and for that reason they built temples at the meeting of three roads.”[11] Servius’ text included a drawing of a crescent moon (representing the new moon), a half moon (representing the waxing moon), and the full moon.

Modern Development

The belief in a singular Triple Moon Goddess was likely brought to modern scholarship, if not originated by, he work of Jane Ellen Harrison.[12][13]

Harrison asserts the existence of female trinities, and uses Epigenes and other ancient sources to elaborate on the Horae, Fates, and Graces as chronological symbols representing the phases of the Moon and the threefold division of the Hellenistic lunar month.[14][15]

However, Harrison’s interpretations and contribution to the development and study of the Triple Goddess were somewhat overshadowed by the more controversial and poorly-supported ideas in her works. Most notably, Harrison used historical sources for the existence of an ancient Triple Moon Goddess to support her belief in an ancient matriarchal civilization, which has not stood up to academic scrutiny.

The “myth and ritual” school or the Cambridge Ritualists, of which Harrison was a key figure, while controversial in its day, is now considered passé in intellectual and academic terms. According to Robert Ackerman, “The reason the Ritualists have fallen into disfavor… is not that their assertions have been controverted by new information… Ritualism has been swept away not by an access of new facts but of new theories.”[16]

As a poet and mythographer, Robert Graves claimed a historical basis for the Triple Goddess. Although Graves’s work is widely discounted by academics as pseudohistory (see The White Goddess § Criticism and The Greek Myths § Reception), it continues to have a lasting influence on many areas of Neopaganism.[17]

Ronald Hutton argues that the concept of the triple moon goddess as Maiden, Mother, and Crone, each facet corresponding to a phase of the moon, is a modern creation of Graves’,[18][19] who in turn drew on the work of 19th and 20th century scholars such as especially Jane Harrison; and also Margaret Murray, James Frazer, the other members of the “myth and ritual” school of Cambridge Ritualists, and the occultist and writer Aleister Crowley.[20]

While Graves was the originator of the idea of the Triple Goddess as embodying Maiden/Mother/Crone, this was not the only trinity he proposed. In his 1944 historical novel The Golden Fleece, Graves wrote “Maiden, Nymph and Mother are the eternal royal Trinity…and the Goddess, who is worshipped…in each of these aspects, as New Moon, Full Moon, and Old Moon, is the sovereign deity.”[21]

Graves did not invent this picture but drew from nineteenth and early twentieth century scholarship. According to Ronald Hutton, Graves used Jane Ellen Harrison’s idea of goddess-worshipping matriarchal early Europe[22][23] and the imagery of three aspects, and related these to the Triple Goddess.[24]

Triple Deity

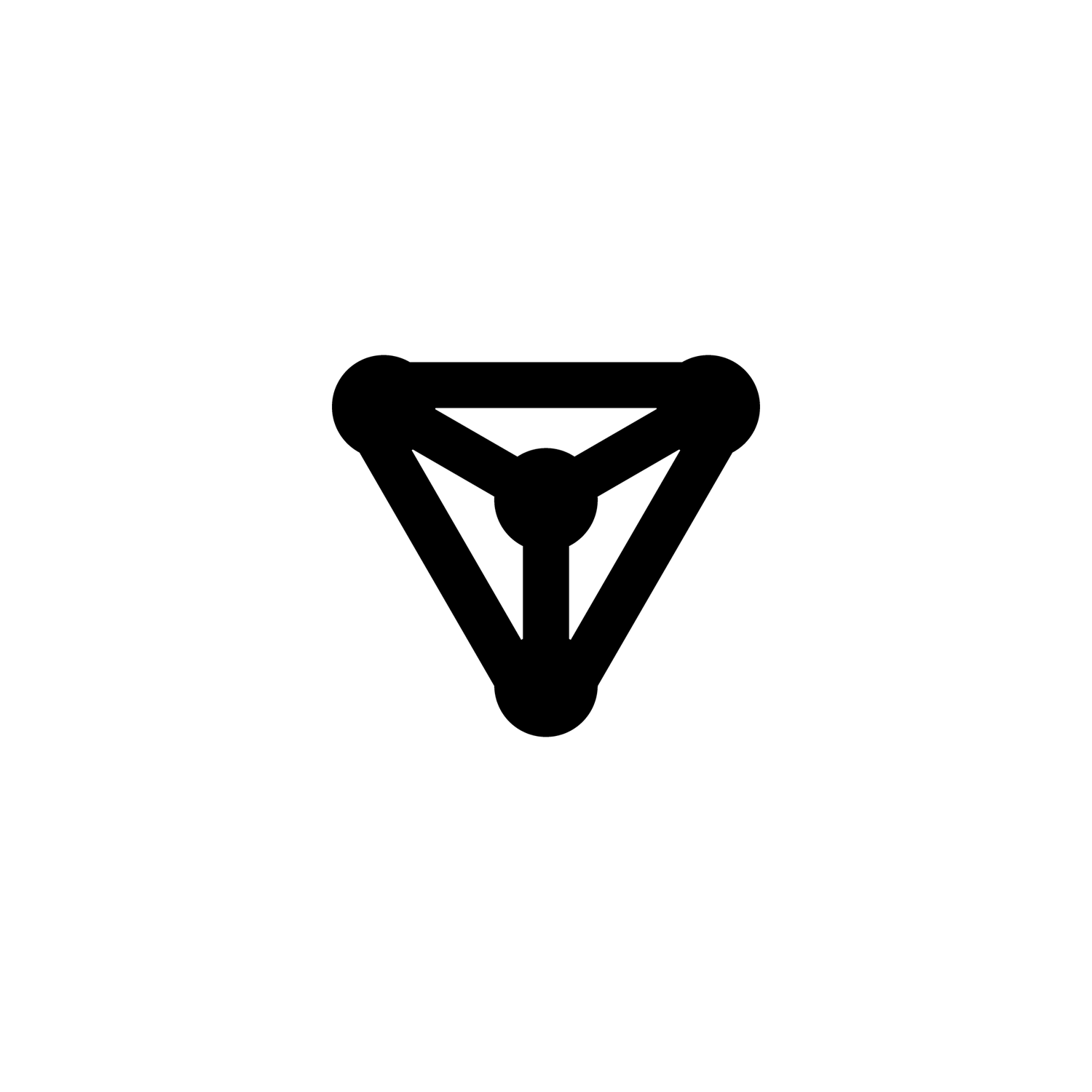

A triple deity is a deity with three apparent forms that function as a singular whole. Such deities may sometimes be referred to as threefold, tripled, triplicate, tripartite, triune, triadic, or as a trinity. The number three has a long history of mythical associations and triple deities are common throughout world mythology. Carl Jung considered the arrangement of deities into triplets an archetype in the history of religion.[25][26][27]

Georges Dumézil proposed in his trifunctional hypothesis that ancient Indo-European society conceived of itself as structured around three activities: worship, war, and toil.[28]

As social structures developed, particular segments of societies became more closely associated with one of the three fundamental activities. These segments, in turn, became entrenched as three distinct “classes”, each one represented by its own god.[29]

In 1970, Dumézil proposed that some goddesses represented these three qualities as different aspects or epithets. Interpreting various deities, including the Iranian Anāhitā and the Roman Juno, he identified what were, in his view, examples of this.[30] Dumézil’s trifunctional hypothesis proved controversial. Many critics view it as a modern imposition onto Indo-European religion rather than an idea present in the society itself.[31][32][33]

The trinity of supreme divinity in Hinduism, in which the cosmic functions of creation, preservation, and destruction are personified as a triad of deities, is called Trimūrti (Sanskrit: त्रिमूर्ति ‘three forms’ or ‘trinity’), where Brahma is considered the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Shiva the destroyer.

The sacred symbol of Hinduism, the Om (or Aum), the sacred sound, syllable, mantra, and invocation, is considered to have an allusion to Trimurti, where the A, U, and M phonemes of the word are considered to indicate creation, preservation and destruction, the which the whole as representing the transcendent or absolute Brahman is added. It also indicates the three basic states of consciousness, in addition to which the whole syllable is interpreted as the subject of the consciousness, the self-principle (Ātman), which is considered to be identical with the Brahman.

The Tridevi is the trinity of goddess consorts for the gods in the Trimurti, typically personified by the Hindu goddesses Saraswati, Lakshmi, and Parvati. In Shaktism, one of the several major Hindu denominations wherein the metaphysical reality, or the godhead, is considered metaphorically to be a woman, these triune goddesses are considered the manifestations of Mahadevi, the Supreme Goddess (the female abolute), also known as Mula-Prakriti or Adi Parashakti.

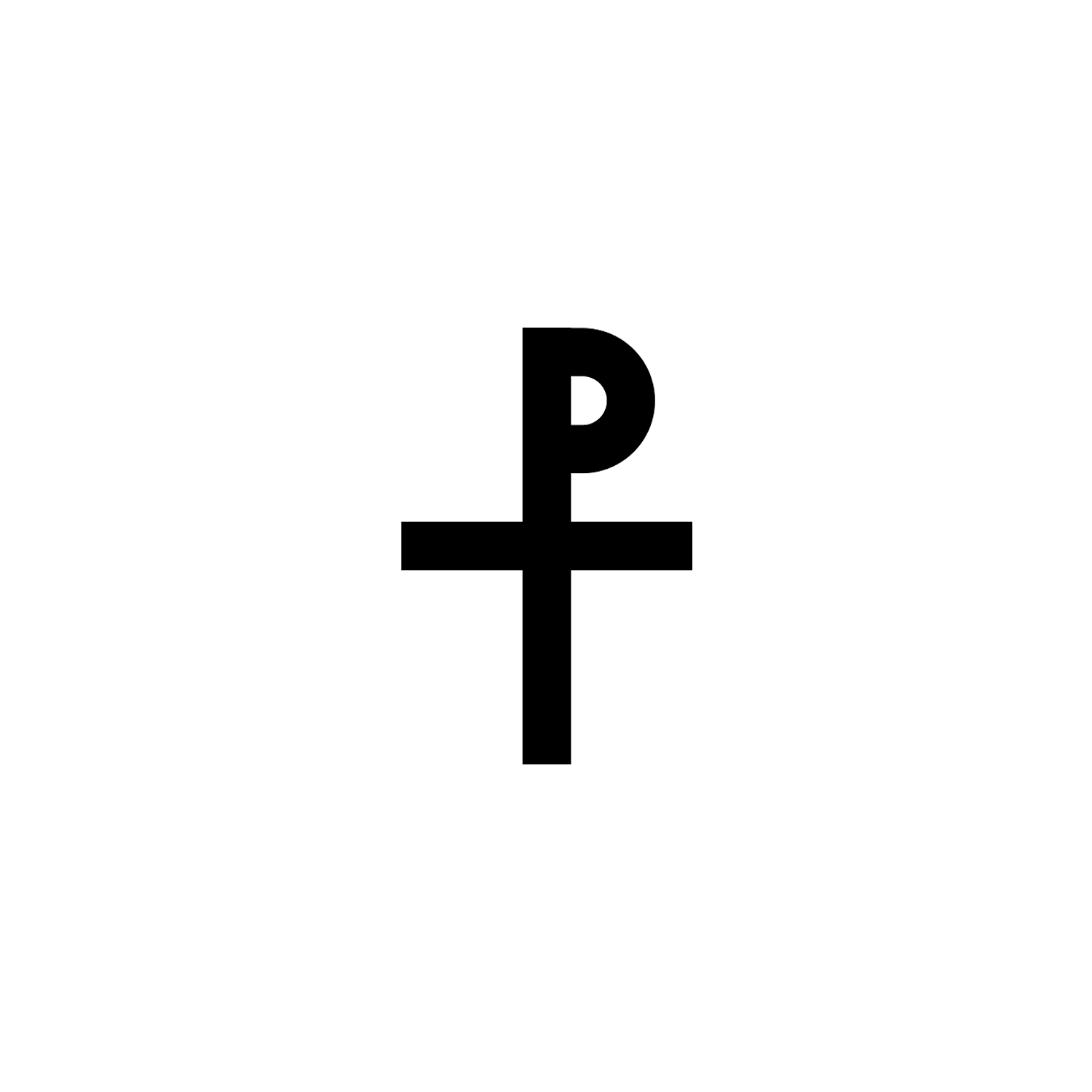

The Roman goddess Diana was venerated from the late sixth century BC as diva triformis, “three-form goddess”,[34] and early on was conflated with the similarly depicted Greek goddess Hekate.[35]

The Matres or Matronae are usually represented as a group of three but sometimes with as many as 27 (3 × 3 × 3) inscriptions. They were associated with motherhood and fertility. Inscriptions to these deities have been found in Gaul, Spain, Italy, the Rhineland and Britain, as their worship was carried by Roman soldiery dating from the mid-first to third century AD.[36]

Miranda Green observes that “triplism” reflects a way of “expressing the divine rather than presentation of specific god-types. Triads or triple beings are ubiquitous in the Welsh and Irish mythic imagery” (she gives examples including the Irish battle-furies, Macha, and Brigit).

Jungian Archetype Theory

The Triple Goddess as an archetype is discussed in the works of both Carl Jung and Karl Kerényi,[37] and the later works of their follower Erich Neumann.[38] Jung considered the general arrangement of deities in triads as a pattern which arises at the most primitive level of human mental development and culture.[39]

In 1949 Jung and Kerényi theorized that groups of three goddesses found in Greece become quaternities only by association with a male god. They give the example of Diana only becoming three (Daughter, Wife, Mother) through her relationship to Zeus, the male deity. They go on to state that different cultures and groups associate different numbers and cosmological bodies with gender.[40]

The threefold division [of the year] is inextricably bound up with the primitive form of the goddess Demeter, who was also Hecate, and Hecate could claim to be mistress of the three realms. In addition, her relations to the moon, the corn, and the realm of the dead are three fundamental traits in her nature. The goddess’s sacred number is the special number of the underworld: ‘3’ dominates the chthonic cults of antiquity.”[41]

Kerenyi wrote in 1952 that several Greek goddesses were triple moon goddesses of the Maiden Mother Crone type, including Hera and others. For example, Kerényi writes:

With Hera the correspondences of the mythological and cosmic transformation extended to all three phases in which the Greeks saw the moon: she corresponded to the waxing moon as maiden, to the full moon as fulfilled wife, to the waning moon as abandoned withdrawing women”.[42]

He goes on to say that trios of sister goddess in Greek myth refer to the lunar cycle; in the book in question he treats Athene also as a triple moon goddess, noting the statement by Aristotle that Athene was the Moon but not “only” the Moon.[42]

In discussing examples of his Great Mother archetype, Neumann mentions the Fates as “the threefold form of the Great Mother”,[43] details that “the reason for their appearance in threes or nines, or more seldom in twelves, is to be sought in the threefold articulation underlying all created things; but here it refers most particularly to the three temporal stages of all growth (beginning-middle-end, birth-life-death, past-present-future).”[44]

Andrew Von Hendy writes that Neumann’s theories are based on circular reasoning, whereby a Eurocentric view of world mythology is used as evidence for a universal model of individual psychological development which mirrors a sociocultural evolutionary model derived from European mythology.[45]

Conclusion

In classical religious iconography or mythological art, three separate beings may represent either a triad who typically appear as a group (the Greek Moirai, Charites, and Erinyes; the Norse Norns; or the Irish Morrígan) or a single deity notable for having three aspects (Greek Hecate, Roman Diana), and other such figures, including the Tridevi of Hinduism.

Traditionally in Wicca, the Goddess is seen as the Triple Goddess, meaning that she is the maiden, the mother and the crone. The Goddess is especially connected to the Moon and stars and the sea, while the Horned God is connected to the Sun and the forests. These are the tribal gods of the witches, just as the Egyptians had their tribal gods Isis and Osiris.

[1] "Pausanias, Description of Greece, Arcadia, chapter 22". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

[2] Servius, Commentary on Virgil's Aeneid 6.118.

[3] Green, C. M. C. (2007). Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[4] Green, C. M. C. (2007). Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521851589.

[5] Lucan: The Civil War, Harvard University Press, 2006

[6] Penguin Classics, Ovid Metamorphoses, 2004

[7] Hutton, Ronald (2001). The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285449-0.

[8] Green, C. M. C. (2007). Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521851589.

[9] Clement of Alexandria, Stromata: Abel, frg. 253.

[10] Jones, P. (2005). "A Goddess Arrives: Nineteenth Century Sources of the New Age Triple Moon Goddess". Culture and Cosmos. 19 (1): 45–70 – via Academia.edu.

[11] Servius, Commentary on the Aeneid, 4.511

[12] Harrison, Jane Ellen (1908) [1903]. Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion (2nd ed.). Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0524043394.

Harrison, Jane Ellen (1912). Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion. Cambridge: University Press.

Harrison, Jane Ellen (1913). Ancient Art and Ritual. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9780837119816.

[13] Harrison 1908, pp. 286ff: Excerpts: "... Greek religion has... a number of triple forms, Women-Trinities.... the trinity-form was confined to the women goddesses. ... of a male trinity we find no trace. ... The ancient threefold goddesses...."

[14] Harrison 1912, pp. 189–192.

[15] Jones, P. (2005). "A Goddess Arrives: Nineteenth Century Sources of the New Age Triple Moon Goddess". Culture and Cosmos. 19 (1): 45–70 – via Academia.edu.

[16] Ackerman, Robert (2002). The Myth and Ritual School: J.G. Frazer and the Cambridge Ritualists. p. 188. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93963-8.

[17] Greer, John Michael (2003). The New Encyclopedia of the Occult. p. 280. Llewellyn. ISBN 978-1567183368.

[18] Ackerman, Robert (2002). The Myth and Ritual School: J.G. Frazer and the Cambridge Ritualists. p. 188. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93963-8.

[19] Hutton, Ronald (March 1997). "The Neolithic great goddess: A study in modern tradition". Antiquity. 71 (271): 91–99. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0008457X. S2CID 153668277.

[20] Hutton, Ronald (2001). The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. p. 41. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285449-0.

[21] Graves, Robert (1945). Hercules, My Shipmate: A Novel. United States: Creative Age Press, Incorporated.

[22] Greer, John Michael (2003). The New Encyclopedia of the Occult. p. 280. Llewellyn. ISBN 978-1567183368.

[23] Hutton, Ronald (March 1997). "The Neolithic great goddess: A study in modern tradition". Antiquity. 71 (271): 91–99. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0008457X. S2CID 153668277.

[24] Seymour, Miranda (2003). Robert Graves: Life on the Edge. p. 307. Scribner. ISBN 978-0743232197.

[25] Bentley Lamborn, Amy (2011). "Revisiting Jung's "A Psychological Approach to the Dogma of the Trinity": Some Implications for Psychoanalysis and Religion". Journal of Religion and Health. 50 (1): 108–119. doi:10.1007/s10943-010-9417-9. ISSN 0022-4197. JSTOR 41349770. PMID 21042858. S2CID 21332730.

[26] Stein, Murray (1990). Moore, Robert L.; Meckel, Daniel (eds.). Jung and Christianity in dialogue: Faith, feminism, and hermeneutics. New York: Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809131877.

[27] "Triads of gods appear very early, at the primitive level. The archaic triads in the religions of antiquity and of the East are too numerous to be mentioned here. Arrangement in triads is an archetype in the history of religion, which in all probability formed the basis of the Christian Trinity." C. G. Jung. A Psychological Approach to the Dogma of the Trinity.

[28] William Hansen, Classical Mythology: A Guide to the Mythical World of the Greeks and Romans (Oxford University Press US, 2005), p. 306_308 online.

[29] The Edinburgh Encyclopedia of Continental Philosophy p. 562

[30] Nāsstrōm, Britt-Mari (1999). "Freyja — The Trivalent Goddess". In Sand, Erik Reenberg; Sørensen, Jørgen Podemann (eds.). Comparative Studies in History of Religions: Their Aim, Scope and Validity. Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 62–64.

[31] Allen, N. J. Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2007.10.53

[32] Benjamin W. Fortson. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction p. 32

[33] Gonda, J. (November 1974). "Dumezil's Tripartite Ideology: Some Critical Observations". The Journal of Asian Studies. 34 (1): 139–149. doi:10.2307/2052415. JSTOR 2052415. S2CID 144109518.

[34] Horace, Carmina 3.22.1.

[35] Green, C.M.C. (2007). Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[36] Takacs, Sarolta A. (2008) Vestal Virgins, Sybils, and Matrons: Women in Roman Religion. University of Texas Press. pp. 118–121.

[37] Jung, C. G.; Kerényi, C. (1949). Essays on a Science of Mythology: the Myth of the Divine Child and the Mysteries of Eleusis. Pantheon Books.

[38] Neumann, Erich (1955). The Great Mother: an Analysis of the Archetype. Pantheon Books.

[39] Jung, Carl Gustav (1966) [1942]. "A Psychological Approach to the Dogma of the Trinity". Psychology and Religion: West and East. Collected Works. Vol. 11 (2nd ed.). Pantheon Books.

[40] Jung, C. G.; Kerényi, C. (1949). Essays on a Science of Mythology: the Myth of the Divine Child and the Mysteries of Eleusis. p. 25. Pantheon Books.

[41] Ibid. p. 167.

[42] Kerényi, C. (1978) [1952]. Athene: Virgin and Mother in Greek Religion. p. 58. Translated by Murray Stein. Zurich: Spring Publications.

[43] Neumann, Erich (1955). The Great Mother: an Analysis of the Archetype. p. 226. Pantheon Books.

[44] Ibid. p. 230.

[45] Von Hendy, Andrew (2002). The Modern Construction of Myth (2nd ed.). Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33996-6. pp. 186–187.

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.