Ankh

Ankh

Also referred to as Key of Life.

Overview

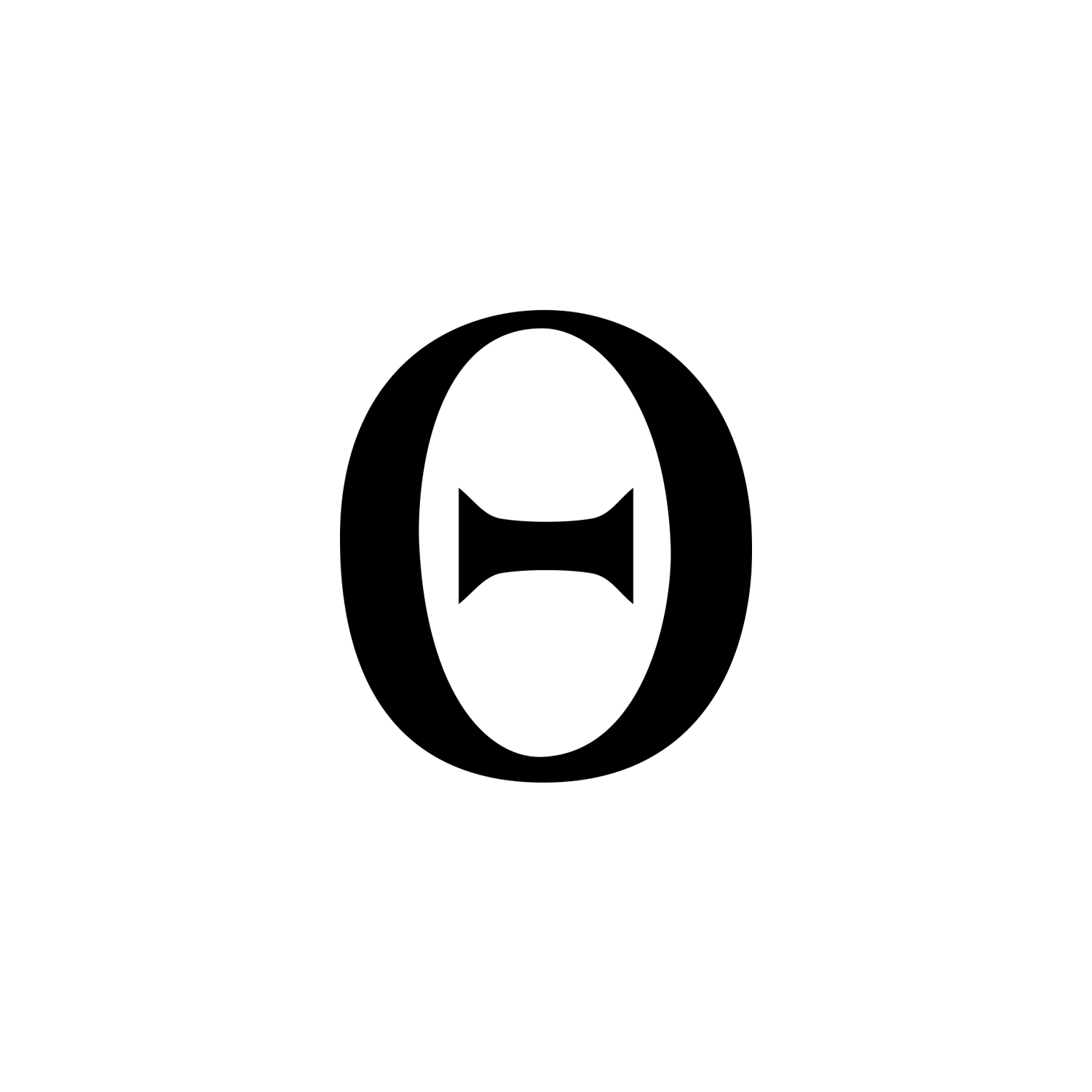

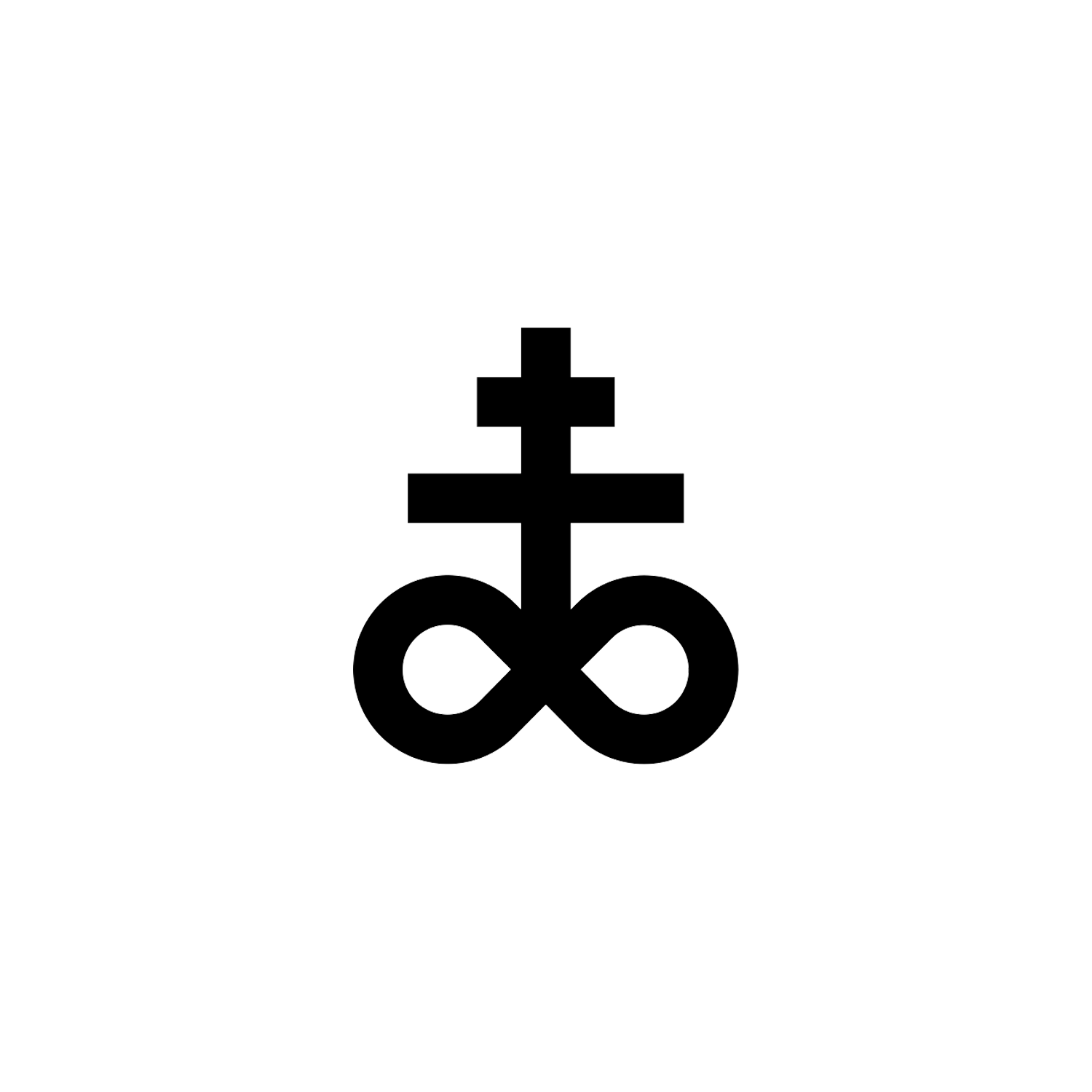

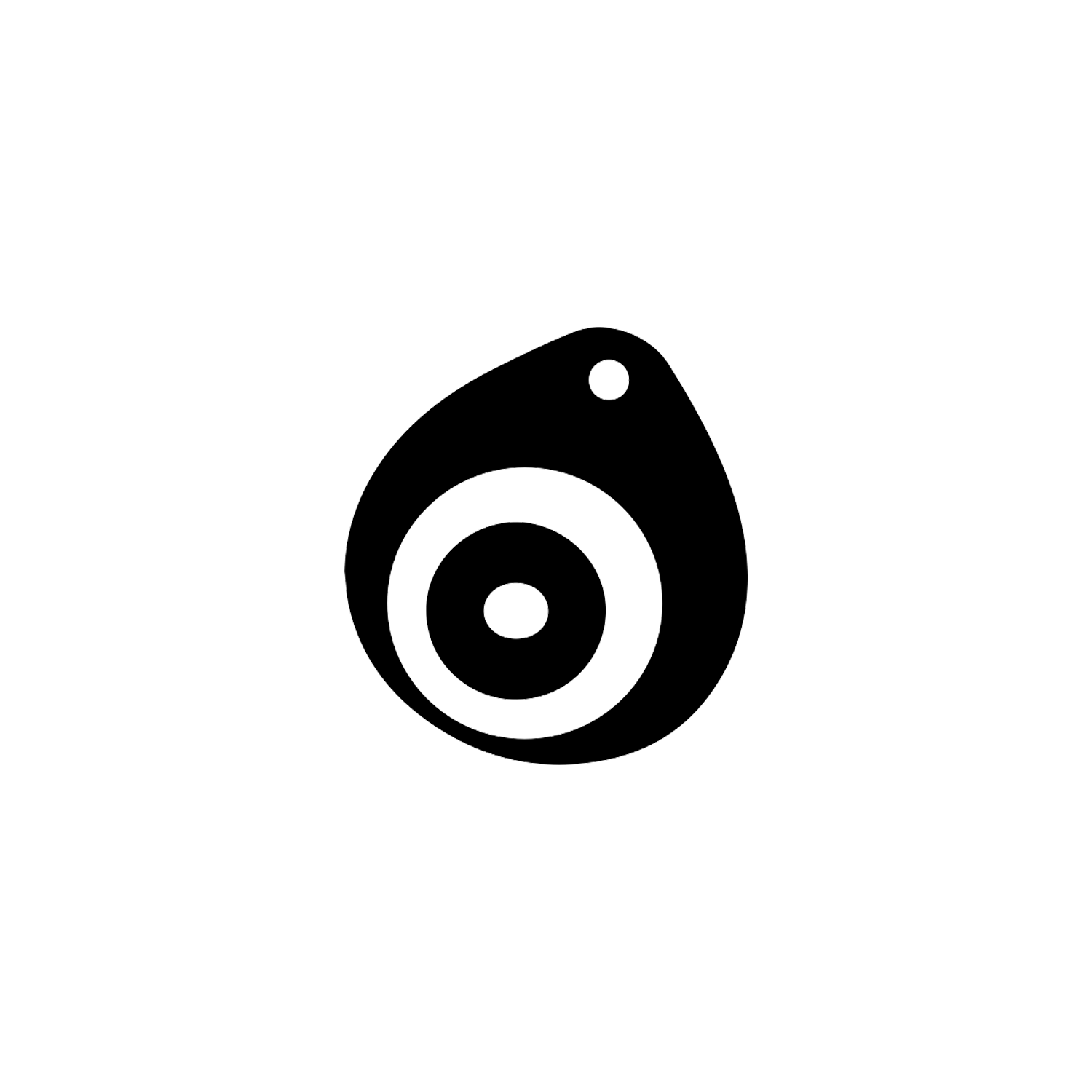

The symbol has a T-shape topped by a droplet-shaped loop. It was used in writing as a triliteral sign, representing a sequence of three consonants, Ꜥ-n-ḫ, found in several Egyptian words.

The Ankh is an Egyptian hieroglyph for “life” or “breath of life” (`nh = ankh) and, as the Egyptians believed that one’s earthly journey was only part of an eternal life, the ankh symbolizes both mortal existence and the afterlife.

Origin and Meaning

In Egyptian art, the ankh frequently appeared as a physical object, symbolizing life or associated elements like air and water. Often portrayed in the grasp of ancient Egyptian gods and occasionally bestowed upon pharaohs, it signified their authority in sustaining life and rejuvenating souls in the afterlife.

The ankh served as a prevalent decorative motif in ancient Egypt, extending its influence to neighboring cultures. Adopted by the Copts as the crux ansata, with a circular loop rather than a droplet, it found usage as a Christian cross variant. In the 1960s, the ankh gained widespread recognition in Western culture as a symbol of African heritage and various Neopagan belief systems.

Early instances of the ankh symbol can be traced back to the First Dynasty[1] (circa 30th to 29th century BC). However, there exists considerable debate regarding the original object represented by the sign.[2]

Many scholars propose that the sign resembles a knot crafted from a pliable material like cloth or reeds.[3] This interpretation stems from early depictions of the ankh, where the lower bar appears as two distinct lengths of flexible material, mirroring the two ends of a knot.[4] Notably, these early renditions bear a resemblance to the tyet symbol, which symbolized “protection.” Consequently, Egyptologists Heinrich Schäfer and Henry Fischer speculated that the two signs shared a common origin[5], suggesting that the ankh served as a knot utilized as an amulet rather than for practical utility.[6][7]

In Gardiner’s compilation of hieroglyphic signs, the ankh is designated as S34, categorizing it alongside articles of clothing and positioned immediately after S33, which represents a sandal.[8] Gardiner’s theory remains relevant; James P. Allen, in a 2014 introductory work on the Egyptian language, proposes that the sign initially denoted a “sandal strap” and illustrates it as an instance of the rebus principle in hieroglyphic script.[9]

Various authors have posited alternative interpretations for the original meaning of the ankh symbol.

Some have proposed a sexual connotation.[10] For instance, Thomas Inman, a nineteenth-century amateur mythologist, suggested that the sign symbolized the union of male and female reproductive organs into a singular glyph.[11]

Similarly, Victor Loret, a nineteenth-century Egyptologist, argued that “mirror” was its original significance. However, Loret acknowledged a flaw in this argument, noting that deities often hold the ankh by its loop, with their hands passing through where the solid reflective surface of a mirror would be in an ankh-shaped object. Egyptologist Andrew Gordon and veterinarian Calvin Schwabe contend that the ankh’s origin is linked to two other signs frequently appearing alongside it, both of uncertain origin: the was-sceptre, representing “power” or “dominion,” and the djed pillar, symbolizing “stability.”[12]

The depth of significance encapsulated within such a simple symbol is truly remarkable. The ankh embodies various concepts, including the male and female reproductive organs, the sunrise, and the convergence of heaven and earth. Its association with the sun is evident in its traditional depiction in gold, symbolizing the radiant color of the sun, rather than in silver, which is associated with the moon. Despite the intricate layers of interpretation surrounding these elements, what is the basic form of the ankh? Its resemblance to a key offers a hint to another dimension of its mystical meaning. According to Egyptian belief, the afterlife holds equal importance to the present existence, and the ankh serves as the key to unlocking the gates of death and revealing what lies beyond.[13]

It is for this reason that ankh figures so prominently in tomb paintings and inscriptions. Deities such as Anubis or Isis are often seen placing the ankh against the lips of the soul in the afterlife to revitalize it and open that soul to a life after death. The goddess Ma’at is frequently depicted holding an ankh in each hand and the god Osiris grasps the ankh in a number of tomb paintings. The association of the ankh with the afterlife and the gods made it a prominent symbol on caskets, for amulets placed in the tomb, and on sarcophagi.

The ankh likely served a decorative purpose more extensively than any other hieroglyphic symbol. Its shape inspired the crafting of mirrors, mirror cases, and floral arrangements, as the sign was employed in inscribing the names of these items. Additionally, various objects such as libation vessels and sistra were fashioned in its likeness. Notably, the ankh frequently adorned architectural elements such as temple walls and shrines.[14]

In these contexts, it often appeared alongside the was and djed symbols, collectively symbolizing “life, dominion, and stability.” Within temple friezes, all three signs or solely the ankh and was were commonly depicted above the hieroglyph for a basket, representing the concept of “all”: “all life and power” or “all life, power, and stability.” Certain deities like Ptah and Osiris could be portrayed wielding a was scepter incorporating elements of the ankh and djed symbols.[15]

In other cultures

During the Middle Bronze Age (approximately 1950–1500 BC), the inhabitants of Syria and Canaan adopted numerous artistic motifs from Egypt, among which hieroglyphs, notably the ankh, predominated. Frequently, it was positioned adjacent to various figures in artworks or depicted being wielded by Egyptian deities who had garnered reverence in the ancient Near East. On occasion, it symbolized concepts such as water or fertility.[16]

In other regions of the Near East, the ankh sign was integrated into Anatolian hieroglyphs to signify “life,” while in the artistic expressions of the Minoan civilization centered on Crete, it found usage. Minoan artwork occasionally fused the ankh or its related tyet symbol with the emblem of the Minoan double axe.[17]

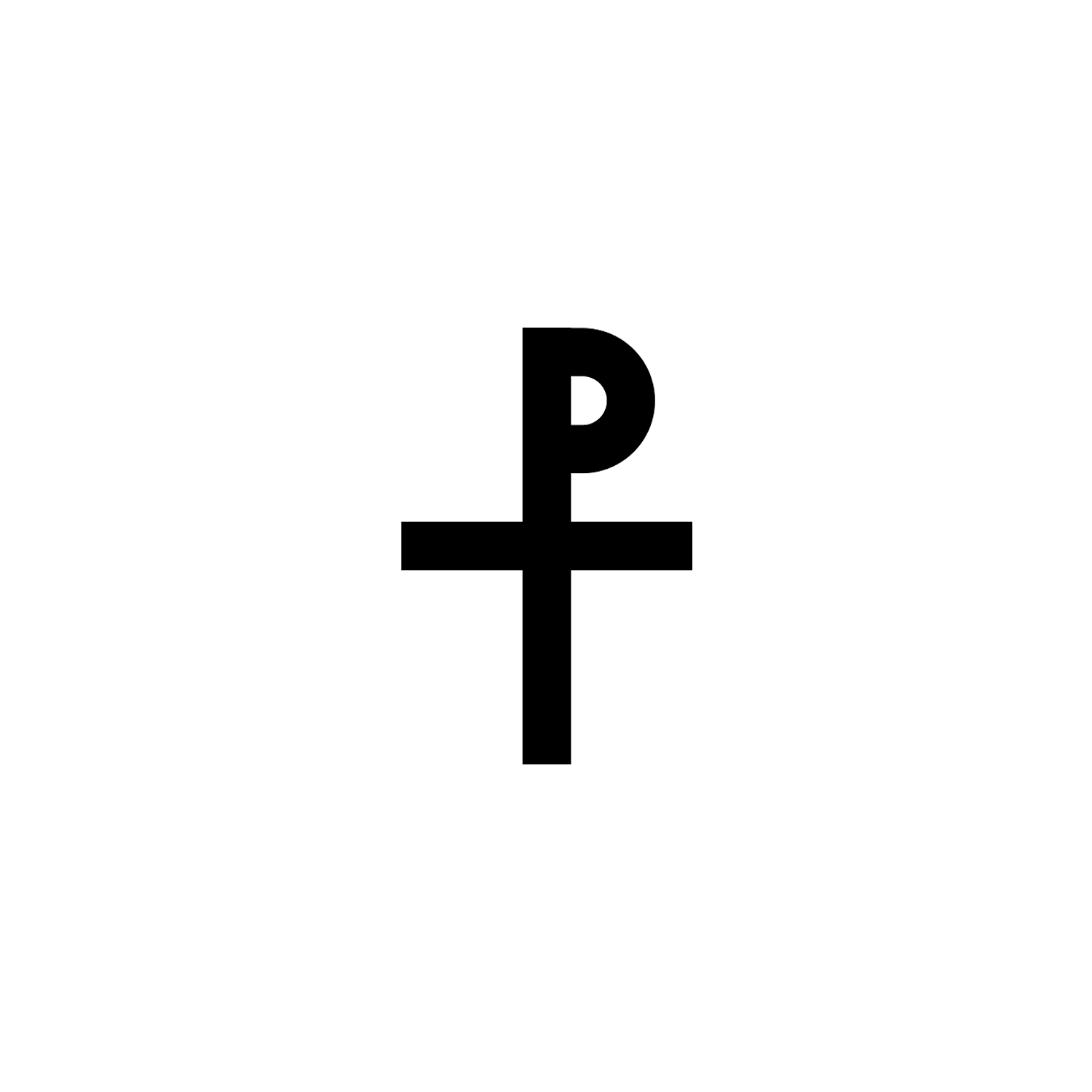

The ankh remained in use as one of the few ancient Egyptian artistic motifs even after the Christianization of Egypt during the 4th and 5th centuries AD.[18] This symbol bears resemblance to the staurogram, a Christian emblem resembling a cross with a loop to the right of the upper bar, utilized by early Christians as a monogram for Jesus[19], as well as the crux ansata, or “handled cross,” which takes the form of an ankh with a circular loop instead of an oval or teardrop-shaped one.

While it has been suggested that the staurogram may have been influenced by the ankh, the earliest Christian usage of this sign dates back to around AD 200, preceding the earliest Christian adoption of the ankh.[20] The earliest documented instance of a crux ansata is found in a copy of the Gospel of Judas from the 3rd or early 4th century AD. The adoption of this symbol could have been influenced by the staurogram, the ankh, or possibly both.[21]

According to Socrates of Constantinople, during the dismantling of Alexandria’s most prominent temple by Christians, the Serapeum, in 391 AD, they discovered cross-like symbols engraved on the stone blocks. Pagans present at the scene interpreted the sign as representing “life to come,” suggesting that the symbol referred to by Socrates was the ankh. However, Christians asserted that the symbol belonged to them, implying that they could readily view the ankh as a crux ansata.[22]

There is limited evidence for the usage of the crux ansata in the western regions of the Roman Empire.[23] Nonetheless, Egyptian Coptic Christians employed it across various mediums, particularly in textile ornamentation.[24]

Conclusion

In more contemporary times, the ankh has experienced a resurgence in popularity within modern Western culture, notably as a favored design for both jewelry and tattoos. This revival traces back to the 1960s counterculture movement, which sparked a renewed fascination with ancient religions.

Today, it stands as the most prominently recognized symbol of African origin in the Western sphere, occasionally embraced by individuals of African descent in the United States and Europe as an emblem of African cultural heritage. Additionally, the ankh holds significance within Kemetism, a cluster of religious movements grounded in the ancient Egyptian religion.[25]

A timeless symbol that may have influenced countless other cultures to adopt and transform it to their tradition. The Ankh’s meaning is vast and it is also referred to as the Key of Life, a symbolic object that could be tied to opening the path to the afterlife, with hieroglyphic translations varying from “life” as a noun, “live” as a verb” and similarities to the word “oath” due to the similar Egyptian writing form for it.[26]

[1] Fischer, Henry G. (1972). "Some Emblematic Uses of Hieroglyphs with Particular Reference to an Archaic Ritual Vessel". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 5: 5–23. doi:10.2307/1512625. JSTOR 1512625. S2CID 191367344. p. 30.

[2] Gordon, Andrew H.; Schwabe, Calvin (2004). The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt. Brill / Styx. ISBN 978-90-04-12391-5. pp. 102–103.

[3] Gordon, Andrew H.; Schwabe, Calvin (2004). The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt. Brill / Styx. ISBN 978-90-04-12391-5. pp. 102–103.

[4] Wilkinson, Richard H. (1992). Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05064-4. p. 177.

[5] Fischer, Henry G. (1972). "Some Emblematic Uses of Hieroglyphs with Particular Reference to an Archaic Ritual Vessel". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 5: 5–23. doi:10.2307/1512625. JSTOR 1512625. S2CID 191367344. p. 13.

[6] Gordon, Andrew H.; Schwabe, Calvin (2004). The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt. Brill / Styx. ISBN 978-90-04-12391-5. pp. 102–103.

[7] Baines, John (1975). "Ankh-Sign, Belt and Penis Sheath". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 3. JSTOR 25149982. p. 1.

[8] Allen, James P. (2014). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, Third Edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05364-9. p. 496.

[9] Allen, James P. (2014). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, Third Edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05364-9. p. 30.

[10] Gordon, Andrew H.; Schwabe, Calvin (2004). The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt. Brill / Styx. ISBN 978-90-04-12391-5. p. 104.

[11] Webb, Stephen (2018). Clash of Symbols: A Ride Through the Riches of Glyphs. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-71350-2. p. 86.

[12] Gordon, Andrew H.; Schwabe, Calvin (2004). The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt. Brill / Styx. ISBN 978-90-04-12391-5. pp. 104, 127–129.

[13] Gardiner, Alan (1915). "Life and Death (Egyptian)". In Hastings, James (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Vol. VIII. pp. 19–25.

[14] Wilkinson, Richard H. (1992). Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05064-4. p. 177.

[15] Wilkinson, Richard H. (1992). Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05064-4. pp. 181, 199.

[16] Teissier, Beatrice (1996). Egyptian Iconography on Syro-Palestinian Cylinder Seals of the Middle Bronze Age. Academic Press Fribourg / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen. pp. 12, 104–107.

[17] Marinatos, Nanno (2010). Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess: A Near Eastern Koine. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03392-6. pp. 122–123.

[18] Du Bourguet, Pierre (1991). "Art Survivals from Ancient Egypt". In Atiya, Aziz Suryal (ed.). The Coptic Encyclopedia. Vol. I. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-897025-7., p. 1.

[19] Hurtado, Larry W. (2006). The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2895-8. p. 136.

[20] Hurtado, Larry W. (2006). The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2895-8. pp. 140, 143–144.

[21] Bardill, Jonathan (2012). Constantine, Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76423-0. pp. 166–167.

[22] Bardill, Jonathan (2012). Constantine, Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76423-0., pp. 167–168.

[23] Bardill, Jonathan (2012). Constantine, Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76423-0. p. 168.

[24] Du Bourguet, Pierre (1991). "Art Survivals from Ancient Egypt". In Atiya, Aziz Suryal (ed.). The Coptic Encyclopedia. Vol. I. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-897025-7. p. 1.

[25] Issitt, Micah L.; Main, Carlyn (2014). Hidden Religion: The Greatest Mysteries and Symbols of the World's Religious Beliefs. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-477-3. p. 328.

[26] Allen, James P. (2014). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, Third Edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05364-9. pp. 34, 317–318.

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.