Mjolnir

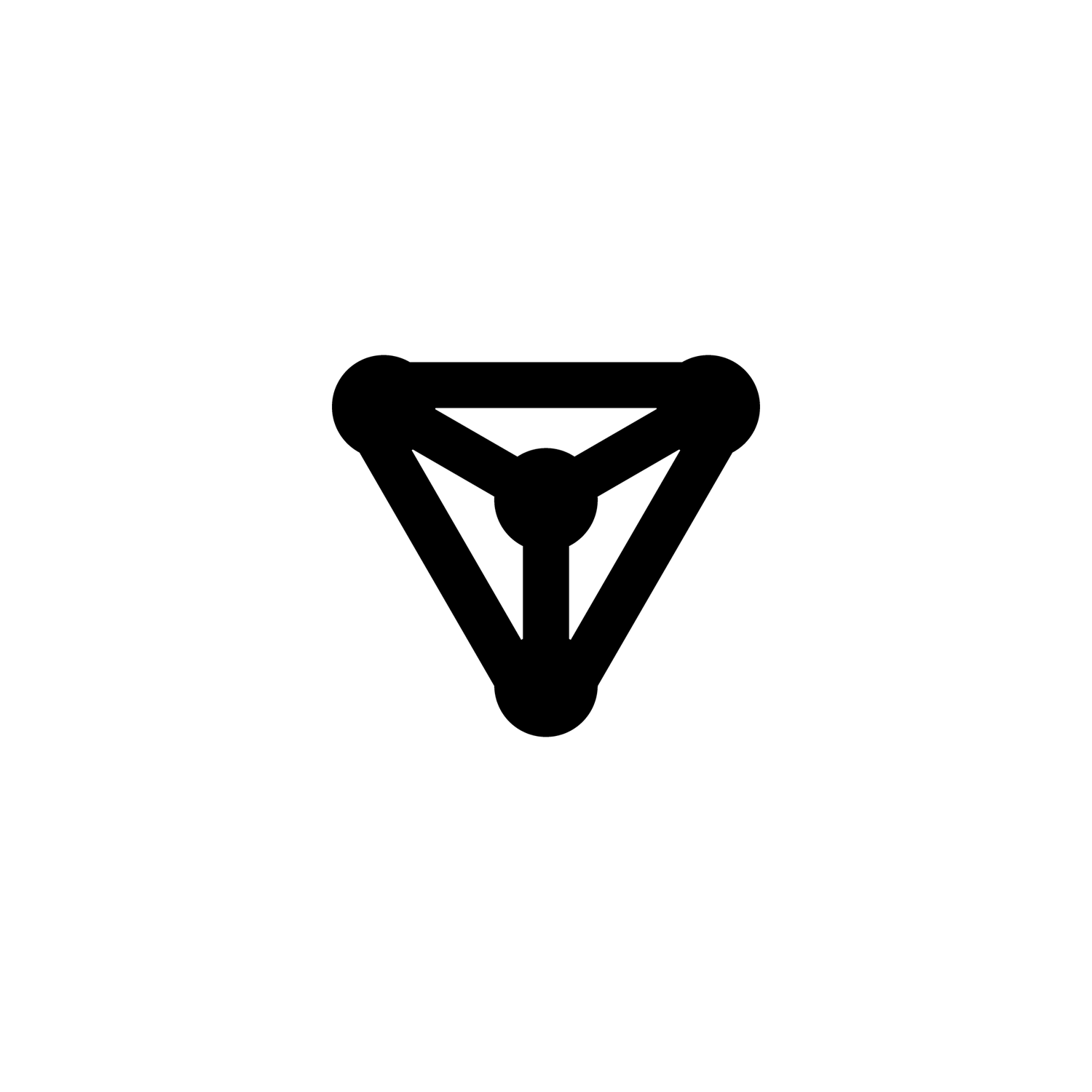

Mjölnir

Also known as Thor's Hammer.

Overview

Mjölnir (from Old Norse Mjǫllnir) is the hammer of the thunder god Thor in Norse mythology, used both as a devastating weapon and as a divine instrument to provide blessings.

The hammer is attested in numerous sources, including the 11th century runic Kvinneby amulet, the Poetic Edda, a collection of eddic poetry compiled in the 13th century, and the Prose Edda, a collection of prose and poetry compiled in the 13th century.

The hammer was commonly worn as a pendant during the Viking Age in the Scandinavian cultural sphere, and Thor and his hammer occur depicted on a variety of objects from the archaeological record. Today the symbol appears in a wide variety of media and is again worn as a pendant by various groups, including adherents of modern Heathenry.

Origin and Meaning

The etymology of the hammer’s name, Mjǫllnir, is disputed among historical linguists. Old Norse Mjǫllnir developed from Proto-Norse *melluniaR and one proposed derivation connects this form to Old Church Slavonic mlunuji and Russian molnija meaning ‘lightning’ (either borrowed from a Slavic source or both stemming from a common source) and subsequently yielding the meaning ‘lightning-maker’.

Another proposal connects Mjǫllnir to Old Norse mjǫll meaning ‘new snow’ and modern Icelandic mjalli meaning ‘the color white’, rendering Mjǫllnir as ‘shining lightning weapon’. Finally, another proposal connects Old Norse Mjǫllnir to Old Norse mala meaning ‘to grind’ and Gothic malwjan ‘to grind’, yielding Mjǫllnir as meaning ‘the grinder’.[1]

Around 1000 pendants in distinctive shapes representing the hammer of Thor have been unearthed in what are today the Nordic countries, England, northern Germany, the Baltic countries, and Russia. Most have very simple designs in iron or silver. Around 100 have more advanced designs with ornaments.

The pendants have been found in a variety of contexts (including at urban sites, and in hoards) and occur in a variety of shapes. Similarly, coins featuring depictions of the hammer have also been discovered.

In 1999, German archaeologist Jörn Staecker proposed a typology for the hammer finds based on decorative style and material properties (such as amber, iron, or silver).

In 2019, American scholar Katherine Suzanne Beard proposed an extension of the typology based on factors such as hammer shape and suspension type.[2] In 2019, Beard also launched Eitri: The Norse Artifacts Database, an online database that lists numerous hammer finds and includes data about their composition and discovery context.[3]

The development of the hammer pendants has been the subject of study by a variety of scholars. The hammers amulets appear to have developed from an earlier tradition of similar pendants among the north Germanic peoples.[4]

Scholars have also noted that the hammer may have developed from a pendant worn by other ancient Germanic people, the so-called club of Hercules amulet.[5]

The increase in popularity of the amulet in the Viking Age and some variants of it shape may have been a response to the use of Christian cross pendants appearing more commonly in the region during the process of Christianization.[4]

The swastika symbol has been identified as representing the hammer or lightning of Thor.[6] Scholar Hilda Ellis Davidson (1965) comments on the usage of the swastika as a symbol of Thor:

The protective sign of the hammer was worn by women, as we know from the fact that it has been found in women’s graves. It seems to have been used by the warrior also, in the form of the swastika. … Primarily it appears to have had connections with light and fire, and to have been linked with the sun-wheel.

It may have been on account of Thor’s association with lightning that this sign was used as an alternative to the hammer, for it is found on memorial stones in Scandinavia besides inscriptions to Thor. When we find it on the pommel of a warrior’s sword and on his sword-belt, the assumption is that the warrior was placing himself under the Thunder God’s protection.[7]

According to runologists Mindy MacLeod and Bernard Mees, “By early modern times, the description ‘Thor’s hammer’ had come to be applied to swastikas (‘sun-wheels’), not the hammer symbols seen in medieval runic inscriptions. Similarly, terms once used for other symbols had also come to be associated with new forms, often of unclear origin.”[8] Other scholars have proposed that the swastika represented Thor’s hammer among the ancient Germanic peoples from an early date.[9]

English folklorist Hilda Ellis Davidson surveys the swastika’s use in the ancient archaeological Germanic record (up to 1964) and concludes that “Thor was the sender of lightning and the god who dealt out both sunshine and rain to men, and it seems likely the swastika as well as the hammer sign was connected with him.”[10]

The Eyrarland Statue, a copper alloy figure found near Akureyri, Iceland dating from around the 11th century, may depict Thor seated and gripping his hammer.[11]

Pictorial representations of Thor’s hammer appear on several runestones, such as DR 26, DR 48 and DR 120 in Denmark and VG 113, Sö 86 and Sö 111 in Sweden.[12]

At least three stones depict Thor fishing for the serpent Jörmungandr, and two of them feature hammers: the Altuna Runestone in Altuna, Sweden and the Gosforth depiction in Gosforth, England.

Thor “is the only known god to have been called on to bless or hallow runestones from the Viking Age”, a fact observed by scholars since at least the 19th century.[13]

The Story

Skáldskaparmál offers an explanation of Mjolnir’s manufacture by the dwarf brothers Eitri and Brokkr.

In this narrative, Loki cuts the hair of Thor’s wife, goddess Sif. Upon discovering this, Thor grabs Loki and threatens to crush every bone in his body if he does not come up with a solution.

Loki swore to go down to Svartalfheim, the land of the dwarves, who were renowned as the greatest smiths in all of the Nine Worlds. There he would obtain a head of hair for Sif that was even more marvelous than the one he had lopped off. Thor consented to this plea bargain. Loki goes to the svartálfar, and for him the Sons of Ivaldi make three special items: Sif’s hair of gold, Freyr’s ship Skíðblaðnir, and Odin’s spear Gungnir.[14]

Seeing this, Loki wagers his head with the dwarf Brokkr on whether his brother Eitri can make three more items of equal quality. As Eitri works on the three precious objects, a fly enters the room and bites him three times: First, the fly lands on the dwarf’s arm and bites it, but Brokkr does not react: He places a pig skin in the forge and from it pulls the golden boar Gullinbursti; second, the fly lands on and bites the back of the dwarf’s neck, but he does not react: after inserting gold, he pulls from the forge Draupnir, a golden ring that produces eight more of itself every nine nights; and third and final, the fly lands on the dwarf’s eyelid and bites him, causing blood to obscure his vision. Nonetheless, Brokkr inserts iron into the forge and pulls from it a hammer, Mjölnir.[14]

The gods Odin, Thor, and Freyr assemble to judge the quality of these items. While reviewing items and explaining their function, Brokkr says the following about Mjölnir:

Then he gave Thor the hammer and said he would be able to strike as heavily as he liked, whatever the target, and the hammer would not fail, and if he threw it at something, it would never miss, and never fly so far that it would not find its way back to his hand, and if he liked, it was so small that it could be kept inside his shirt. But there was this defect in it that the end of the hammer was rather short.[15]

The three assembled gods judge the hammer to be the best of all the objects, and the tale continues without further mention of the object.[15]

Potential Proto-Indo-European origins

Nordic Bronze Age petroglyphs depict figures holding hammers and hammer-like weapons, such as axes. Some scholars have proposed these to depict precursors to Mjölnir. As scholar Rudolf Simek summarizes, “as the Bronze Age rock carvings of axe or hammer-bearing god-like figures show, [Mjölnir] played a role as a consecratory instrument early on, probably in a fertility cult … “.[16]

Thor is one of various deities associated with or personifying thunder who wields a hammer-like object associated with phenomena such as lightning or fire in a variety of myth bodies. In some cases these hammer-like objects return to the deity when thrown or result in changes in weather.

Examples frequently cited by scholars include Vedic Indra, who wields a lightning spear; Jupiter, who throws lightning bolts; and the Celtic deity Dagda, who carries a club. Numerous scholars have identified the concept of Thor and his hammer, like Indra, Zeus, and the Dagda, as stemming from Proto-Indo-European mythology.[17]

Modern depictions

Mjölnir is depicted in a variety of media in the modern era. As noted by Rudolf Simek, in art “Thor is almost always depicted with [Mjölnir]”, but how the hammer appears in modern depictions varies: At times it may appear as hammer-like depictions of the club of Hercules, to a large sledge hammer, and displaying influence from the archaeological record.[18]

A variety of locations, organizations, and objects are named after the hammer. Examples include Mjølnerparken in Copenhagen, Denmark; the Mjølnir crater, a meteorite crater off the coast of Norway; the Hammer of Thor monument in Quebec, Canada; the Norwegian football club FK Mjølner; and a variety of ship names, including the HNoMS Mjølner (1868) and several ships by the name of HSwMS Mjölner.

In the modern era, Mjölnir pendants are worn by a variety of people and for a variety of purposes.[19]

For example, the symbol is commonly used by adherents of Heathenry, a new religious movement.[20] Also termed Heathenism, contemporary Germanic Paganism, or Germanic Neopaganism, it is a modern Pagan religion.

Developed in Europe during the early 20th century, its practitioners model it on the pre-Christian religions adhered to by the Germanic peoples of the Iron Age and Early Middle Ages. In an attempt to reconstruct these past belief systems, Heathenry uses surviving historical, archaeological, and folkloric evidence as a basis, although approaches to this material vary considerably.

Writing in 2006, scholars Jenny Blain and Robert J. Wallis observe that “the most common of heathen sacred artefacts is Thor’s hammer” and add that “heathen spirituality is expressed visually and publicly in a number of ways, such as the display of reproduced artefacts (for example, Thor’s hammer as a pendant … ), pilgrimages to sacred sites (and votive offerings left there), and ‘visits’ to museum collection displays of artefacts which offer direct visual (and other resonant) links to ancient religions.”[21]

The symbol has seen some use in white nationalist and neo-Nazi circles. Scholar Katherine Beard notes that “most people who wear hammer pendants today do so for cultural, religious, or decorative reasons and maintain absolutely no ties to any racist groups or beliefs”.[22]

Conclusion

Of all of the symbols in Norse mythology, Thor’s Hammer (Old Norse Mjöllnir) is one of the most historically important, and is probably the best known today.

The hammer was his primary weapon. It was no ordinary hammer; whenever Thor cast it at an enemy, it returned to his hands like a boomerang.[23]

Thor (whose name goes back to a Proto-Germanic root that means “Thunder”[24]) was the god of the storm, and thunder was perceived as being the sound of his hammer crashing down on his foes. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the Old Norse name for his hammer, Mjöllnir, probably meant “Lightning.”

Thor’s hammer was certainly a weapon – the best weapon the Aesir had, in fact – but it was more than just a weapon. It also occupied a central role in rituals of consecration and hallowing. The hammer was used in formal ceremonies to bless marriages, births, and probably funerals as well.[25]

[1] Simek, Rudolf. 1993. A Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Trans. Angela Hall. pp. 219-220.

[2] Beard, Katherine Suzanne. 2019. Hamarinn Mjǫllnir:The Eitri Database and the Evolution of the Hammer Symbol in Old Norse Mythology. MA database project. University of Iceland. Online.

[3] Eitri: The Norse Artifacts Database may be viewed online here Archived 20 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine (last accessed 18 January 2021). Beard developed the database as part of her MA thesis at the University of Iceland under superivision by Terry Gunnell. Some of these entries may also be found in Beard 2019: 171–228.

[4] Beard 2019: 124–125.

[5] Simek 1993: 14–15.

[6] The symbol was identified as such since 19th century scholarship; examples include Worsaae (1882:169) and Greg (1884:6).

[7] Ellis Davidson, H. R. (1965). "Thor's Hammer". Folklore. pp. 12-13. Taylor & Francis: 1–15. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1965.9716982. JSTOR 1258087.

[8] MacLeod, Mindy & Bernard Mees. 2006. Runic Amulets and Magic Objects. p. 252. Boydel & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84383-205-8

[9] For discussion on this topic, see Beard 2019: 23–24.

[10] Davidson 1965: 82–83.

[11] Orchard, Andy. 1997. Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. p. 161. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

[12] McKinnell, John; Simek, Rudolf; Düwel, Klaus (2004). "Gods and Mythological Beings in the Younger Futhark" (PDF). Runes, Magic and Religion: A Sourcebook. Studia Medievalia Septentrionalia. Vol. 10. pp. 116–133. Vienna: Fassbaender. ISBN 978-3-900538-81-1.

[13] Beard 2019: 119.

[14] Faulkes, Anthony. 1987. Trans. Edda. p. 96. Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

[15] Ibid. p. 97.

[16] Simek 2007: 219.

[17] Cf. Beard 2019: 31, 39, 41.

[18] Simek 2007: 220.

[19] See discussion in Beard 2019: 9–11.

[20] Simek 2007: 220.

[21] Blain, Jenny & Robert J. Wallace. 2006. "Representing Spirit: Heathenry, New-Indigenes and the Imaged Past" in Ian Russell, editor. Images, Representations and Heritage, p. 90–93. Springer. ISBN 0-387-32215-9

[22] Beard 2019: 10.

[23] Simek 2008: 219.

[24] Orel, Vladimir. 2003. A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. p. 429.

[25] Ellis-Davidson, Hilda Roderick. 1964. Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. p. 80.

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.