Eye of Horus

Eye of Horus

Also known as left wedjat eye or udjat eye.

Overview

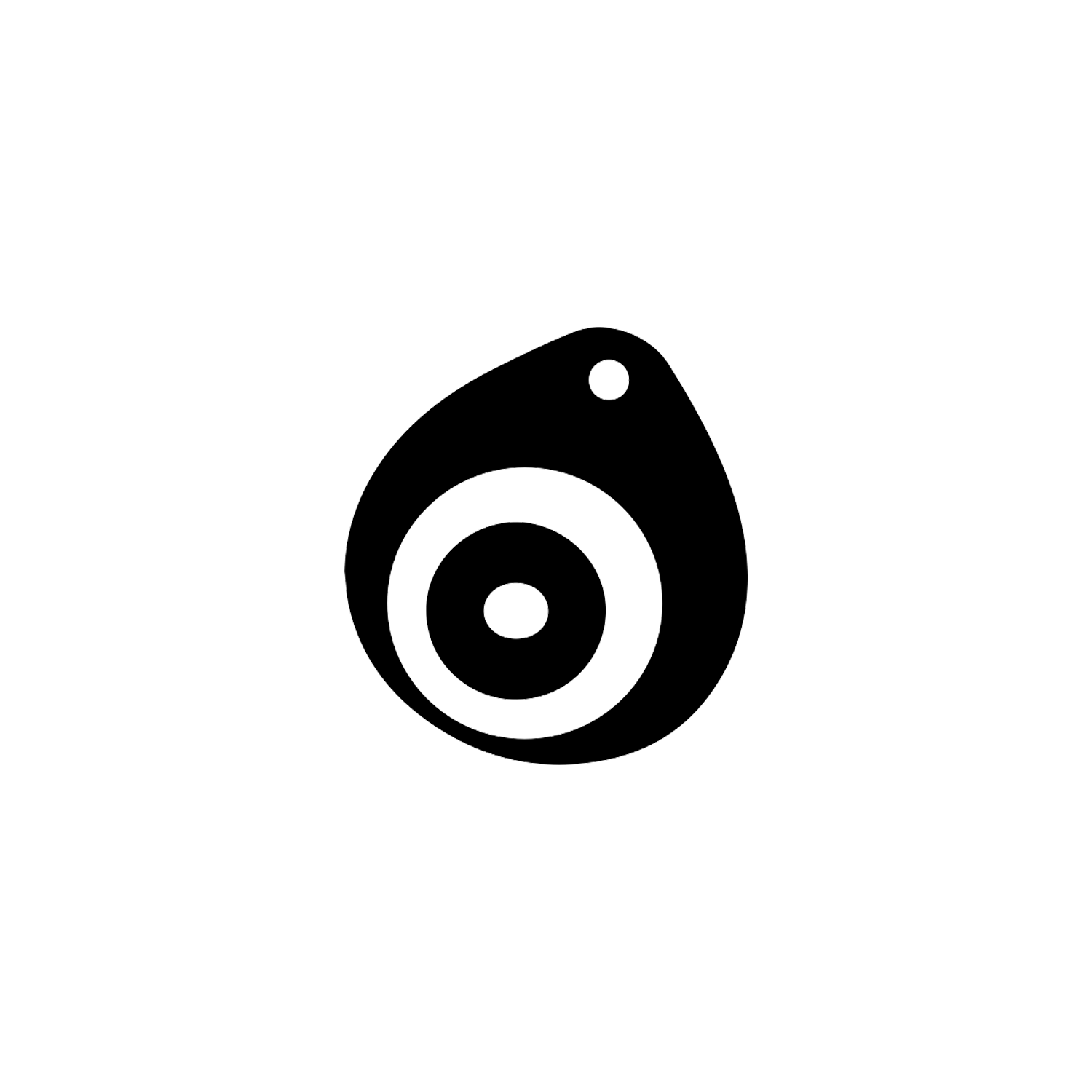

The Eye of Horus, also known as left wedjat eye or udjat eye, specular to the Eye of Ra (right wedjat eye), is a concept and symbol in ancient Egyptian religion that represents well-being, healing, and protection. The eye symbol was also rendered as a hieroglyph (𓂀).

Horus was represented as a falcon, such as a lanner or peregrine falcon, or as a human with a falcon head. The Eye of Horus is a stylized human or falcon eye. The symbol often includes an eyebrow, a dark line extending behind the rear corner of the eye, a cheek marking below the center or forward corner of the eye, and a line extending below and toward the rear of the eye that ends in a curl or spiral. The cheek marking resembles that found on many falcons. The Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson suggests that the curling line is derived from the facial markings of the cheetah, which the Egyptians associated with the sky because the spots in its coat were likened to stars.

The stylized eye symbol was used interchangeably to represent the Eye of Ra. Egyptologists often simply refer to this symbol as the wedjat eye.

Origin and Meaning

The Eye of Horus symbology derives from the mythical conflict between the god Horus with his rival Set, in which Set tore out or destroyed one or both of Horus’s eyes and the eye was subsequently healed or returned to Horus with the assistance of another deity, such as Thoth. Horus subsequently offered the eye to his deceased father Osiris, and its revitalizing power sustained Osiris in the afterlife. The Eye of Horus was thus equated with funerary offerings, as well as with all the offerings given to deities in temple ritual. It could also represent other concepts, such as the moon, whose waxing and waning was likened to the injury and restoration of the eye.

The Eye of Horus symbol, a stylized eye with distinctive markings, was believed to have protective magical power and appeared frequently in ancient Egyptian art. It was one of the most common motifs for amulets, remaining in use from the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC) to the Roman period (30 BC – 641 AD). Pairs of Horus eyes were painted on coffins during the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC) and Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC). Other contexts where the symbol appeared include on carved stone stelae and on the bows of boats. To some extent the symbol was adopted by the people of regions neighboring Egypt, such as Syria, Canaan, and especially Nubia.

The ancient Egyptian deity Horus was revered as a sky god, with texts often describing his right eye as the sun and his left eye as the moon.[1] The solar and lunar eyes were occasionally linked to Egypt’s red and white crown, respectively.[2] While some texts appear to interchange the Eye of Horus with the Eye of Ra[3], which typically represents the power of the sun god Ra. Richard H. Wilkinson suggests a gradual distinction between the lunar Eye of Horus and the solar Eye of Ra.[4] However, other scholars argue that the association between Horus’s eyes and the sun and moon wasn’t clearly established until the New Kingdom period.[5]

Katja Goebs proposes that the myths surrounding the Eye of Horus and the Eye of Ra share a common core element, suggesting a flexible myth centered on the structural relationship of a missing or displaced object. In these myths, the goddess associated with the eye flees from Ra and is later retrieved by another deity. Similarly, in the narratives involving the Eye of Horus, the eye is often absent due to conflicts between Horus and his rival Set over the kingship of Egypt following the death of Horus’s father Osiris. That being said the agreed symbol for the Eye of Horus is the one with the tail going to the right, whereas the right wedjat eye of Ra has a tail that goes left.

The Eye of Horus mythology begins with the story of Osiris. This story is the most recognized mythology in ancient Egypt. It illustrates the eternal fight between the virtuous, the sinful, and the punishment. Osiris was the oldest son of the God of the Earth, Geb, and the Goddess of the Sky, Nut, and was known as the God of the

Underworld but, more appropriately, as the God of Transition, Resurrection, and Regeneration. Osiris had three siblings: Isis, Set, and Nephthys. Osiris married his sister, Isis, as was the timely Royal custom, and had a son named Horus. The myth started when Set, Osiris’ brother, murdered Osiris to claim the throne, which caused disorder and chaos in ancient Egypt. Set’s brutality did not stop at killing Osiris, and he proceeded to cut Osiris’ body into 14 parts that were distributed across ancient Egypt. According to the ancient Egyptian traditions, in order for a royal’s spirit to cross to the underworld, the body needed to be appropriately embalmed and buried in the royal tombs. This proper burial allowed the body to pass through the underworld gates and be judged according to their deeds.

Isis traveled with Horus in search of Osiris’s body parts. Isis also recruited the help of her sister, Nephthys, and Nephthys’ son, Anubis. Anubis was the son of Nephthys and Osiris, and it is said that Nephthys wickedly assumed the shape of Isis to seduce Osiris and conceive Anubis. Isis, Nephthys, Anubis, and Horus were able to find 13 parts of Osiris. The spirit of Osiris was then able to pass to Amenti, the underworld, and rule the dead. When Horus killed Set in the large battle near Edfu, he proclaimed his kingdom, restoring the order to Egypt.

The conflict between Horus and Set, as described in the Pyramid Texts[6] dating back to the late Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC), features prominently in Egyptian mythology. In these texts, Set is depicted as stealing the Eye of Horus, sometimes even trampling and consuming it. However, Horus typically retrieves the eye, often through force. This narrative of the eye’s theft and restoration is elaborated in various texts from later periods, with Thoth frequently portrayed as the deity responsible for restoring the eye, sometimes after it was torn into pieces by Set. In the Book of the Dead from the New Kingdom, Set is described as transforming into a black boar when injuring Horus’s eye. In another text from the late New Kingdom, Set gouges out both of Horus’s eyes, which miraculously transform into lotuses overnight.

Hathor is credited with restoring Horus’s eyes by anointing them with gazelle’s milk in this narrative.[7] In later mythological texts from the Ptolemaic Period, Isis is said to water the buried eyes, causing them to grow into grapevines. The restoration of the eye is often referred to as “filling” the eye, with Hathor filling Horus’s eye sockets with gazelle’s milk, while Greco-Roman temple texts attribute the filling of the eye to Thoth and a group of fourteen other deities using specific plants and minerals. This process is likened to the waxing of the moon, with the fifteen deities symbolizing the fifteen days from the new moon to the full moon.[8]

The ancient Egyptians used this legendary fight as a metaphor of the battle between good and evil, order and chaos. Afterward, Horus was idolized by the ancient Egyptians in the form of the Eye of Horus, which was considered as a symbol of prosperity and protection.

In the New Kingdom era[2][9], the Eye of Horus came to be known as the wḏꜣt (often spelled as wedjat or udjat), which translates to the “whole,” “complete,” or “uninjured” eye.[10] The precise meaning of wḏꜣt remains unclear, whether it refers to the eye that was damaged and then restored, or to the one Set left unscathed.[11]

After ascending to kingship following Set’s defeat, Horus honors his deceased father by presenting offerings, thereby rejuvenating and sustaining him in the afterlife. This act served as a mythic precedent for the offerings made to the deceased, a significant aspect of ancient Egyptian funerary practices. It also influenced the development of ritual offerings performed on behalf of deities in temples.[12]

Among the offerings presented by Horus is his own eye, which Osiris consumes. As Osiris’s son, the eye ultimately derives from Osiris himself. Thus, in this context, the eye symbolizes the Egyptian concept of offerings. According to this belief, the gods were the source of all the goods offered to them, making offerings a part of the gods’ essence. By receiving offerings, deities were replenished with their own life force, akin to Osiris’s rejuvenation upon consuming the Eye of Horus. In the Egyptian worldview, life emanated from the gods and permeated the world, and offering rituals served to maintain the flow of life by returning this vital force to the gods.[13][14]

The act of offering the eye to Osiris exemplifies the mythic theme in which a deity in need is restored to well-being through the receipt of an eye.[15] Given its restorative properties, the eye was regarded by the Egyptians as a symbol of protection against malevolent forces, in addition to its other symbolic meanings.[11]

Ritualistic significance

In the Osiris myth, the act of presenting the Eye of Horus to Osiris served as the fundamental model for all funerary offerings and broader offering rituals. This analogy extended to human offerings to deities, where the giver represented Horus and the recipient symbolized Osiris.[16] Additionally, the Egyptian term for “eye,” jrt, bore resemblance to jrj, meaning “act,” allowing the Eye of Horus to be associated with any ritual gesture through wordplay. Consequently, the Eye of Horus came to symbolize the entirety of sustenance provided to the gods within the temple cult.[17] Variations of the myth depicting flowers or grapevines sprouting from the buried eyes further underscored the eye’s connection to ritual offerings, as these plants yielded perfumes, food, and beverages commonly employed in offering ceremonies.[18] Moreover, the eye was frequently linked with maat, the Egyptian principle of cosmic order, which relied on the perpetuation of temple rituals and could be equated with various types of offerings.[19]

Amulets shaped like the wedjat eye emerged in the late Old Kingdom and remained in production until the Roman era.[20] Ancient Egyptians typically interred their deceased with amulets, and among these, the Eye of Horus was consistently favored. It stood out as one of the most prevalent forms of amulet discovered on Old Kingdom mummies and retained its popularity for over two millennia, despite the increasing variety and quantity of funerary amulets. During the Old Kingdom, wedjat amulets were typically positioned on the chest of the deceased, but during and after the New Kingdom, they were frequently placed over the incision where the body’s internal organs had been extracted during the embalming process.[21]

Wedjat amulets were made from a wide variety of materials, including Egyptian faience, glass, gold, and semiprecious stones such as lapis lazuli. Their form also varied greatly.[22]

Other Uses and Cultures

Wedjat eyes were depicted in various contexts throughout Egyptian art. During the First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom, coffins often featured a pair of wedjat eyes painted on the left side. Mummies were typically oriented to face left during this time, suggesting that the eyes were intended to enable the deceased to gaze outward from the coffin, while also serving as protective symbols. Similarly, boats often bore eyes of Horus painted on their bows, believed to safeguard the vessel and provide foresight. Occasionally, wedjat eyes were depicted with wings, positioned protectively over kings or deities.[23] Stelae, carved stone slabs, frequently displayed inscriptions alongside wedjat eyes. In certain periods of Egyptian history, only deities or kings could be depicted directly beneath the winged sun symbol found in the lunettes of stelae, with Eyes of Horus placed above representations of common people.[24] Additionally, the wedjat symbol was sometimes incorporated into tattoos, as evidenced by the mummy of a late New Kingdom woman adorned with intricate tattoos featuring several wedjat eyes.[25]

Beyond Egypt, neighboring cultures adopted the wedjat symbol in their own artistic expressions. During the Middle Bronze Age, artistic motifs from Egypt, including the wedjat, influenced art in Canaan and Syria, albeit less frequently than other Egyptian symbols like the ankh.[26] Conversely, the wedjat enjoyed greater prominence in the art of the Kingdom of Kush in Nubia during the first millennium BC and early first millennium AD, showcasing Egypt’s significant cultural influence on Kush.[27] Today, the tradition of painting eyes on the bows of ships persists in numerous Mediterranean countries, possibly tracing its origins back to the ancient practice of adorning boats with the wedjat eye.[28]

Connection with Neuroanatomy

The Eye of Horus has been used for many metaphors over the years, i.e., “Eye of the Mind, Third Eye, Eye of the Truth or Insight, the Eye of God Inside the Human Mind.”

The ancient Egyptians, because of their beliefs in the Eye of Horus’ mystic powers, gave all of these names to the Eye of Horus. There is however an anatomical relevance which has been documented by a study.[29]

Artistically, the Eye is comprised of six different parts. From the mythological standpoint, each part of the Eye is considered to be an individual symbol. Additionally, parts of the Eye represent terms in the series 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, and 1/32; when this image is superimposed upon a sagittal image of the human brain, it appears that each part corresponds to the anatomic location of a particular human sensorium [Figure 2]. The study highlighted the possible scientific speculation of the ingenuity of ancient Egyptians’ remarkable insight into human anatomy and physiology.

Ancient Egyptians were pioneers in art and medicine. This is exemplified in the artistic measurements of the Eye of Horus. The Eye of Horus was divided into six different parts called the Heqat fractions, in which each part was considered a symbol itself. The Heqat is among the oldest Egyptian measuring systems in which the numerical values are perceived as a consequential pattern. Gay Robins and Charles Shute discussed this concept in their explanation of the ancient Egyptian mathematical measures of “The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus”, which is considered to be the oldest ancient mathematical script. In the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, the Heqat was described as a unit of volume, which is used for measurements of goods, such as grain and flour, and it was approximated as 4.8 liters, just over one gallon.

The Eye of Horus fragments were organized together to form the whole Eye, similar to the myth, and these fragments were given a series of numerical values with a numerator of one and dominators to the powers of two: 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, 1/32, and 1/64. Some historians suggested that each part of the eye represents one of the six senses: smell, sight, thought, hearing, taste, and touch.

The 1/2 accounts for the sense of smell, the 1/4 represents sight, the 1/8 represents thought, the 1/16 represents hearing, the 1/32 represents taste, and the 1/64 represents touch (Figure 1). Surprisingly, if we superimposed these suggested parts over the mid-sagittal image of the human brain, each component corresponds to portions of human neuroanatomical features.

This study goes in extensive detail of each part and its correlation to the human brain, but it is beyond the scope of this article, so I urge you to read it in its entirety using the link [29] in the references section at the bottom.

Conclusion

A masterpiece of symbology, The Eye of Horus was used as a sign of prosperity and protection, derived from the myth of Isis and Osiris. Its meaning is not singular, and to understand it you first need to learn the history behind it.

It can be seen in tombs, amulets and even boats. Note the difference from the Eye of Ra (right wedjat eye), which is sometimes used interchangeably with the Eye of Horus. The hieroglyph for the latter has the tail end going to the right–as it is known as the left wedjat eye.

The symbol also has an astonishing connection between neuroanatomical structure and function. From mythology to a modern day talisman.

[1] Wilkinson, Richard H. (1992). Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05064-4.

[2] Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5.

[3] Krauss, Rolf (2002). "The Eye of Horus and the Planet Venus: Astronomical and Mythological References". In Steele, John M.; Imhausen, Annette (eds.). Under One Sky: Astronomy and Mathematics in the Ancient Near East. Ugarit-Verlag. pp. 193–208. ISBN 3-934628-26-5.

[4] Wilkinson, Richard H. (1992). Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05064-4.

[5] Eaton, Katherine (2011). "Monthly Lunar Festivals in the Mortuary Realm: Historical Patterns and Symbolic Motifs". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 70 (2): 229–245. doi:10.1086/661260. JSTOR 661260. S2CID 163404019.

[6] Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5.

[7] Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5.

[8] Kaper, Olaf E. (2001). "Myths: Lunar Myths". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 480–482. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

[9] Kaper, Olaf E. (2001). "Myths: Lunar Myths". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 480–482. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

[10] Faulkner, Raymond O. (1991) [1962]. A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian. Griffith Institute. ISBN 978-0-900416-32-3.

[11] Andrews, Carol (1994). Amulets of Ancient Egypt. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70464-0.

[12] Assmann, Jan (2001) [German edition 1984]. The Search for God in Ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3786-1.

[13] Frandsen, Paul John (1989). "Trade and Cult". In Englund, Gertie (ed.). The Religion of the Ancient Egyptians: Cognitive Structures and Popular Expressions. S. Academiae Ubsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-554-2433-6.

[14] Shafer, Byron E (1997). "Temples, Priests, and Rituals: An Overview". In Shafer, Byron E (ed.). Temples of Ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press. pp. 1–30. ISBN 0-8014-3399-1.

[15] Goebs, Katja (2002). "A Functional Approach to Egyptian Myth and Mythemes". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. 2 (1): 27–59. doi:10.1163/156921202762733879.

[16] Assmann, Jan (2001) [German edition 1984]. The Search for God in Ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3786-1.

[17] Lorton, David (1999). "The Theology of Cult Statues in Ancient Egypt". In Dick, Michael B. (ed.). Born in Heaven, Made on Earth: The Making of the Cult Image in the Ancient Near East. Eisenbrauns. pp. 123–210. ISBN 978-1-57506-024-8.

[18] Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5.

[19] Shafer, Byron E (1997). "Temples, Priests, and Rituals: An Overview". In Shafer, Byron E (ed.). Temples of Ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press. pp. 1–30. ISBN 0-8014-3399-1.

[20] Andrews, Carol (1994). Amulets of Ancient Egypt. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70464-0.

[21] Ikram, Salima; Dodson, Aidan (1998). The Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05088-0.

[22] Andrews, Carol (1994). Amulets of Ancient Egypt. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70464-0.

[23] Wilkinson, Richard H. (1992). Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05064-4.

[24] Robins, Gay (2008). The Art of Ancient Egypt, Revised Edition. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03065-7.

[25] Watson, Traci (12 May 2016). "Intricate animal and flower tattoos found on Egyptian mummy". Nature. 53 (155): 155. Bibcode:2016Natur.533..155W. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19864. PMID 27172024. S2CID 4465165.

[26] Teissier, Beatrice (1996). Egyptian Iconography on Syro-Palestinian Cylinder Seals of the Middle Bronze Age. Academic Press Fribourg / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen.

[27] Elhassan, Ahmed Abuelgasim (2004). Religious Motifs in Meroitic Painted and Stamped Pottery. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-84171-377-9.

[28] Potts, Albert M. (1982). The World's Eye. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-1387-6.

[29] The Eye of Horus: The Connection Between Art, Medicine, and Mythology in Ancient Egypt (2019). National Library of Medicine.

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.