Monad

Monad

Also known as Monas Hieroglyphica or The Hieroglyphic Monad.

Overview

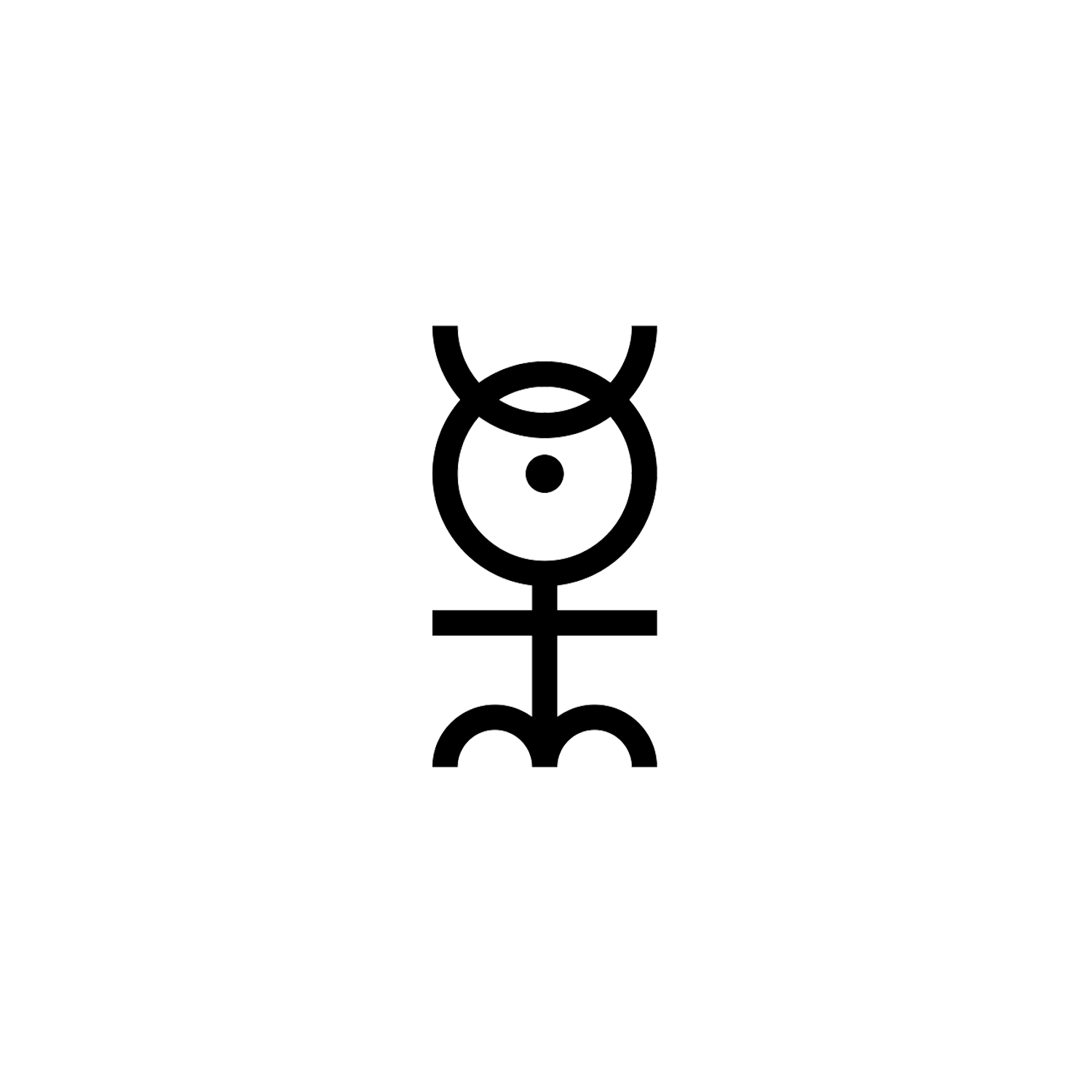

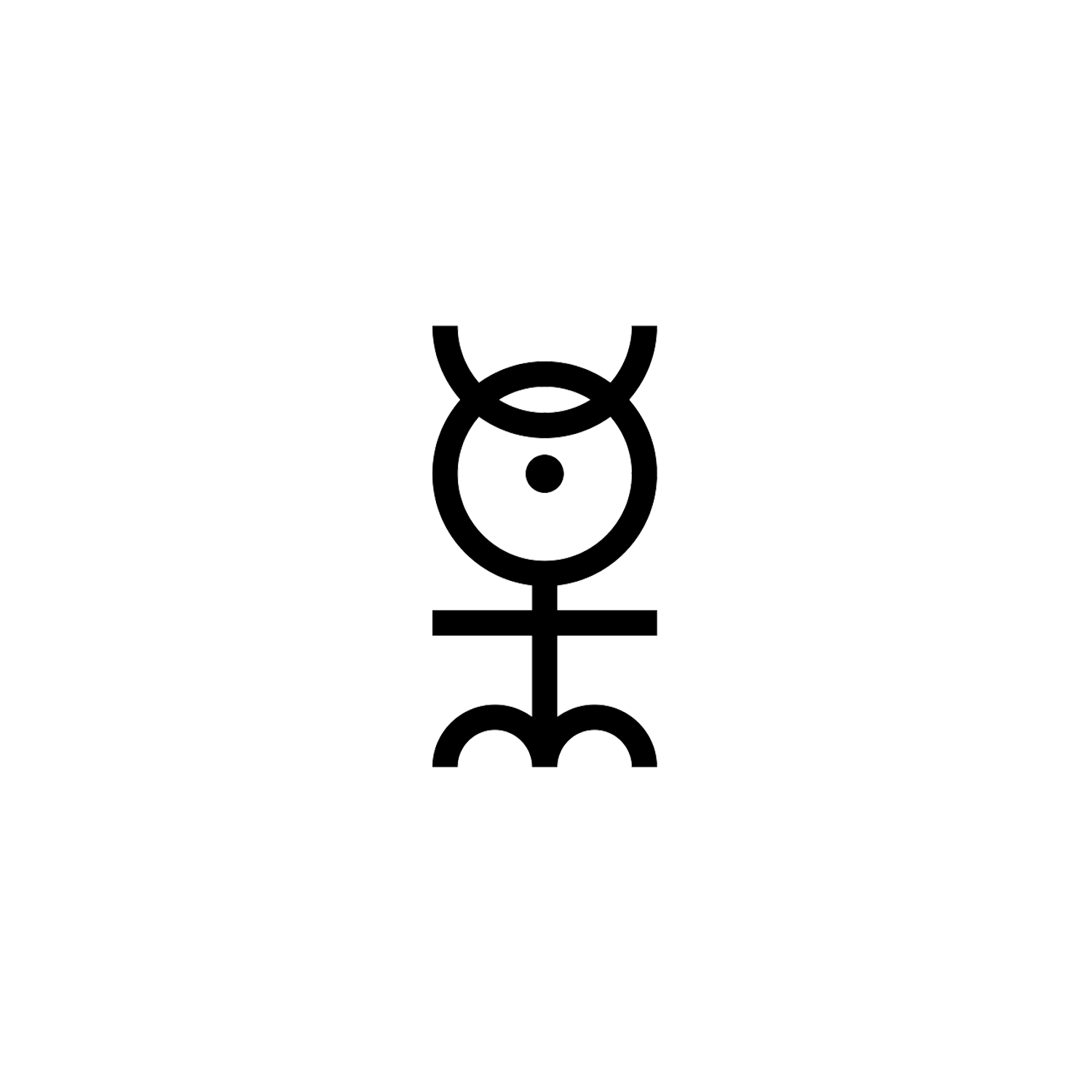

This complex symbol was meant to symbolize the unity of all creation, influenced by astrological and planetary forces. The glyph is a combination of other symbols with varying meanings and historical backgrounds.

Its intention was to encapsulate the interconnected worldview, combining elements of astrology, alchemy, mysticism, and metaphysics.

Origin and Meaning

Monas Hieroglyphica (or The Hieroglyphic Monad) is a book by John Dee, the Elizabethan magus and court astrologer of Elizabeth I of England, published in Antwerp in 1564. It is an exposition of the meaning of an esoteric symbol that he invented.

Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica presents a complex emblem constructed from various astrological symbols, with elements of Latin wordplay, capitalization, spacing, and diacritics, rendering its interpretation challenging. The symbol is intended to embody a profound concept, representing the unity of all creation influenced by celestial forces. Dee believed that this symbol contained the essence of alchemical transformation and spiritual evolution, and by meditating upon it, he aimed to access hidden knowledge transcending linguistic barriers. In merging astrology, alchemy, mysticism, and metaphysics, the Hieroglyphic Monad serves as a visual manifestation of Dee’s interconnected worldview.

John Dee intended the Monad to incorporate a wide range of mystical and esoteric concepts. This complex symbol was meant to symbolize the unity of all creation, influenced by astrological and planetary forces. Dee believed it held the essence of alchemical transformation and spiritual growth. By meditating on the Monad, he thought to gain insights into hidden knowledge about the universe, transcending language barriers and tapping into profound truths. Overall, Dee’s intention was to encapsulate his interconnected worldview, combining elements of astrology, alchemy, mysticism, and metaphysics.

Understanding the text is difficult because of Dee’s Latin wordplay, unexplained capitalization, odd spacing and diacritics.[1]

To understand the symbol’s meaning better, we need to understand who its author is. John Dee (13 July 1527 – 1608 or 1609) was an English mathematician, astronomer, teacher, astrologer, occultist, and alchemist.[2] He was the court astronomer for, and advisor to, Elizabeth I, and spent much of his time on alchemy, divination, and Hermetic philosophy. As an antiquarian, he had one of the largest libraries in England at the time. As a political advisor, he advocated the foundation of English colonies in the New World to form a “British Empire”, a term he is credited with coining.[3]

Dee eventually left Elizabeth’s service and went on a quest for additional knowledge in the deeper realms of the occult and supernatural. He aligned himself with several individuals who may have been charlatans, travelled through Europe, and was accused of spying for the English crown.[4] Upon his return to England, he found his home and library vandalised. He eventually returned to the Queen’s service, but was turned away when she was succeeded by James I. He died in poverty in London, and his gravesite is unknown.

In 1555 Dee was arrested and charged with the crime of “calculating”, because he had cast horoscopes of Queen Mary and Princess Elizabeth. The charges were raised to treason against Mary.[5][6] Dee appeared in the Star Chamber and exonerated himself, but was turned over to the Catholic bishop Edmund Bonner for religious examination. His strong, lifelong penchant for secrecy may have worsened matters. The episode was the most dramatic in a series of attacks and slanders that dogged Dee throughout his life. Clearing his name yet again, he soon became a close associate of Bonner.[7]

Dee presented Queen Mary in 1556 with a visionary plan for preserving old books, manuscripts and records and founding a national library, but it was not taken up.[8] Instead, he expanded his personal library in Mortlake, acquiring books and manuscripts in England and on the Continent. Dee’s library, a centre of learning outside the universities, became the greatest in England and attracted many scholars.[9]

When Elizabeth succeeded to the throne in 1558, Dee became her astrological and scientific advisor. He chose her coronation date and even became a Protestant.[10][11][12] From the 1550s to the 1570s, he served as an advisor to England’s voyages of discovery, providing technical aid in navigation and political support to create a “British Empire”, a term he was the first to use.[3]

In 1564, Dee wrote the Hermetic work Monas Hieroglyphica (“The Hieroglyphic Monad”), an exhaustive Cabalistic interpretation of a glyph of his own design, meant to express the mystical unity of all creation.

Having dedicated it to Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor in an effort to gain patronage, Dee attempted to present it to him at the time of his ascension to the throne of Hungary. The work was esteemed by many of Dee’s contemporaries, but cannot be interpreted today in the absence of the secret oral tradition of that era.[13]

The Monad in Other Works

Giordano Bruno in De monade, numero et figura liber (1591; “On the Monad, Number, and Figure”) described three fundamental types: God, souls, and atoms.[14]

The idea of monads was popularized by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in Monadologia (1714)[14]. In Leibniz’s system of metaphysics, monads are basic substances that make up the universe but lack spatial extension and hence are immaterial. Each monad is a unique, indestructible, dynamic, soullike entity whose properties are a function of its perceptions and appetites. Monads have no true causal relation with other monads, but all are perfectly synchronized with each other by God in a preestablished harmony. The objects of the material world are simply appearances of collections of monads.

Alchemy and the Monad

The glyph first appeared in Dee’s earlier text on astronomy, Propaedeumata Aphoristica (1558), but in the Monas Hieroglyphica it became the central focus of the work. One of his most incomprehensible texts, it draws parallels between and ascribes cabbalistic meaning to the physical properties of certain minerals, their governing planets according to alchemical theories of the day, and the geometry of their alchemical and astrological symbols. The result is a complex web of meaning that is not fully understood even today.

Some believe that the Monas Hieroglyphica was intended as a textbook to accompany lessons delivered orally by Dee but now lost; others believe that it is a hidden treatise on cryptography to be used in espionage. Whatever its original purpose, Dee’s hieroglyph became a cornerstone of hermetic philosophy and a significant influence on the Rosicrucians, a secret society which venerated the images of the rose (symbolising resurrection) and the cross (symbolising redemption). Dee himself is frequently associated with the Rosicrucians, although there is no evidence that he ever belonged to the society, or that it even existed prior to his death in 1608.

In certain cosmic philosophies and cosmogonies, the term “monad” (derived from the Ancient Greek words μονάς (monas) meaning ‘unity,’ and μόνος (monos) meaning ‘alone’) signifies the fundamental or primal substance. Initially formulated by the Pythagoreans, the Monad represents the highest entity, encompassing divinity or the entirety of existence.[15]

The circled dot was used by the Pythagoreans and later Greeks to represent the first metaphysical being, the Monad or the Absolute. The circumpunct is also the center part of the head of The Hieroglyphic Monad, at point 7:.

The grid above taken from THEOREM XII in the book, shows the glyph broken down, each segment bearing a meaning. The Sun, Moon, Taurus, Aries, a Cross representing the elements, as well as other symbols that Dee has attributed planetary, astrological and alchemical meanings to.

The symbolism of the Monad also represents an interpretive exploration connected to the Christian Trinity. Alan of Lille references the Trismegistus’ Book of the Twenty-Four Philosophers, which suggests that a Monad can singularly produce another Monad, a concept many adherents of this faith perceive as the emergence of God the Son from God the Father, whether through generation or creation. This assertion is similarly echoed by the pagan author of the Asclepius, who is occasionally associated with Trismegistus. [16]

Pythagoras reportedly journeyed through Asia, Africa, and Europe, where he underwent initiation into multiple priesthoods. This learned philosopher cultivated a profound understanding across various disciplines, particularly in geometry, or what is akin to Masonry.

Among his contributions in this realm was the formulation of numerous problems and theorems, notably the celebrated Euclid’s 47th problem—upon its discovery, the moment was commemorated with a hecatomb (100 cattle) sacrifice.

What remains lesser-known is Pythagoras’ utilization of this symbol to represent the Monad.

Conclusion

This is John Dee’s enigmatic treatise on symbolic language. Although published in 1564 at age 37, he considered it valuable throughout his life.

The Monas is a highly esoteric work with a distorted meaning. In it he claims himself in possession of the most secret mysteries.

He wrote it in twelve days while apparently in a peak (mystical) state: “[I am] the pen merely of [God] Whose Spirit, quickly writing these things through me, I wish and I hope to be.”[17]

He claims it will revolutionize astronomy, alchemy, mathematics, linguistics, mechanics, music, optics, magic, and adeptship.

[1] Turner, Nancy; Burnes, Teresa (2007). "A Partial Re-Translation of John Dee's Monas Hieroglyphica - Nancy Turner and Teresa Burnes". Journal of the Western Mystery Tradition. 2 (13).

[2] Roberts, R. Julian (25 May 2006). "Dee, John (1527–1609)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7418.

[3] Williams, Gwyn A. (1985). When was Wales?: A History of the Welsh. p. 124. Black Raven Press. ISBN 978-0-85159-003-5.

[4] Szönyi, György E. (2004a). "John Dee and Early Modern Occult Philosophy". p. 4. Literature Compass. 1 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1111/j.1741-4113.2004.00110.x. ISSN 1741-4113.

[5] Fell Smith, Charlotte (1909). The Life of Dr. John Dee (1527–1608). London: Constable & Co. ISBN 9781291940411.

[6] Lysons, Daniel (1792). "Mortlake". The Environs of London: County of Surrey. Vol. 1. London: T Cadell and W Davies. pp. 364–88. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007.

[7] Fell Smith, Charlotte (1909). The Life of Dr. John Dee (1527–1608). London: Constable & Co. ISBN 9781291940411.

[8] Fell Smith, Charlotte (1909). The Life of Dr. John Dee (1527–1608). London: Constable & Co. ISBN 9781291940411.

[9] "Books owned by John Dee". St. John's College, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 25 September 2006

[10] Poole, Robert (29 February 1996). "John Dee and the English Calendar: Science, Religion and Empire". hermetic.ch. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020.

[11] Szönyi, György E. (2004a). "John Dee and Early Modern Occult Philosophy". Literature Compass. 1 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1111/j.1741-4113.2004.00110.x. ISSN 1741-4113.

[12] Szönyi, György E. (2004b). John Dee's Occultism: Magical Exaltation through Powerful Signs. p. 246. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791462232.

[13] Forshaw, Peter J. (2005). "The Early Alchemical Reception of John Dee's Monas Hieroglyphica". Ambix. 52 (3). Maney: 247–269. doi:10.1179/000269805X77772. S2CID 170221216. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020.

[14] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in Monadologia (1714), Encyclopaedia Britannica.

[15]

Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm, Freiherr von (2005). Discourse on metaphysics, and the monadology. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486443102.

[16] Gilson, Etienne (February 15, 2019). "From Scotus Eriugena to Saint Bernard". History of Christian Philosophy in the Middle Ages. Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press. p. 174,809. ISBN 9780813231952. OCLC 1080547285

[17] Dee, John: MONAS HIEROGLYPHICA ('THE HIEROGLYPHIC MONAD') (1564). esotericarchives.com

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.