Circumpunct

Circumpunct

Also referred to as circled dot.

Overview

A symbol with widespread importance across multiple fields of study, the circumpunct (☉) appears in alchemy, religion, mythology, mathematics, musical theory and more.

It is a circle with a point at its centre, a trivial symbol with a vast significance and history behind it.

Origin and Meaning

“The most primitive and fundamental of all symbols is the dot.” — Manly P. Hall; Lectures on Ancient Philosophy

The circumpunct symbol, known more commonly as “the circle with the dot in the middle,” has existed for millennia. It holds various symbolic meanings, ranging from representing gold in alchemy[1] to serving as a European road sign indicating the city center. Predominantly, it is utilized as a solar symbol, with its origins traced back to ancient Egypt. Reputable sources attribute its beginnings to Ra (or Re), the god associated with the midday sun. In Egyptian hieroglyphs, the circle with a midpoint, along with a vertical line, signifies “sun.”[2]

Within Hinduism, the center point within the circle is referred to as a “bindu,” denoting a point or dot. It is believed to symbolize the essence of male life, representing the pivotal moment when creation initiates within the cosmic womb, transitioning from unity to multiplicity.

In Hindu metaphysics, Bindu is considered the point at which creation begins and may become unity. It is also described as “the sacred symbol of the cosmos in its unmanifested state”.[3][4] Bindu is the point around which the mandala is created, representing the Universe.[5]

According to Gnostics, it is the most primal aspect of God. To Greek philosophers and the Pythagoreans, the circumpunct represents God, or the Monad – the point of the beginning of creation, and eternity.[6]

Manly P. Hall, a prominent scholar of Freemasonry and a 33rd-degree Mason, delved into the significance of the circumpunct in his lectures on Ancient Philosophy.[7]

“The keys to all knowledge are contained in the dot, the line, and the circle. The dot is universal consciousness, the line is universal intelligence, and the circle is universal force – the threefold, unknowable Cause of all knowable existence (the three hypostases of Atma).

In the First Degree ritual, Freemasons are taught about the point within a circle or the circumpunct.

The uncyphered ritual states: “Lodges in ancient times were dedicated to King Solomon, he being our first Most Excellent Grand Master; in modern times to St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist – two eminent Christian patrons of Freemasonry; and since their time there has been represented, in every regular and well furnished lodge, a certain point within a circle, embordered by two perpendicular parallel lines, representing St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist. On top of the circle rests the book of Holy Scriptures; the point represents an individual brother, the circle the boundary line of his duty. In going round this circle we necessarily touch on the two parallel lines, as well as on the book of Holy Scriptures; and while a Mason keeps himself circumscribed within their precepts, it is impossible that he should materially err.”[8]

What isn’t explicitly disclosed is that the point at the center of the circle holds additional connotations.

Circumpunct in Alchemy

The ancient alchemical symbol for gold was often represented by the point within the circle.[1] Gold is also one of the three ingredients for the preparation of The Philosopher’s Stone in alchemy, an object which was believed to convert base metals to gold.[9] With scepticism put to the side, the search of this mystical object laid the groundwork for modern chemistry.

Gold is one of the seven metals of alchemy (gold, silver, mercury, copper, lead, iron & tin). For the alchemist, it represented the perfection of all matter on any level, including that of the mind, spirit, and soul. Being a metal that does not corrode, symbolizing immortality and due to that it has continually been used in medicine from ancient times to today. Paracelsus, who was a pioneer in several aspects of the “medical revolution” of the Renaissance and also a notable alchemist, recommended potable gold as a cure for many illnesses.[10]

Throughout history and across diverse cultures, gold has been esteemed for its aesthetic allure and distinctive physical and chemical attributes. Consequently, the emergence of alchemy, a pseudoscience aimed at transforming base metals into the revered “king of metals,” was a natural progression observed in various civilizations since ancient times. The concept of transmutation stemmed from observations of the ubiquitous changes observed in nature, coupled with the application of analogies and correspondences. Its theoretical underpinnings were rooted in different theories of matter, which sought to simplify the complex array of material substances into fundamental “elements.”

Noteworthy among these theories were the concepts of the Two Contraries and the Five Elements (Chinese tradition), the Four Elements (Greek philosophy), the Sulphur-Mercury Theory (Arabic tradition), and the Tria Prima (Paracelsus).

In alchemy, the term chrysopoeia (from Ancient Greek χρυσοποιία (khrusopoiía) ‘gold-making’) refers to the artificial production of gold, most commonly by the alleged transmutation of base metals such as lead.[11]

Monad and the Pythagoreans

In certain cosmic philosophies and cosmogonies, the term “monad” (derived from the Ancient Greek words μονάς (monas) meaning ‘unity,’ and μόνος (monos) meaning ‘alone’) signifies the fundamental or primal substance. Initially formulated by the Pythagoreans, the Monad represents the highest entity, encompassing divinity or the entirety of existence.[6]

The circled dot was used by the Pythagoreans and later Greeks to represent the first metaphysical being, the Monad or the Absolute.

The symbolism represents an interpretive exploration connected to the Christian Trinity. Alan of Lille references the Trismegistus’ Book of the Twenty-Four Philosophers, which suggests that a Monad can singularly produce another Monad, a concept many adherents of this faith perceive as the emergence of God the Son from God the Father, whether through generation or creation. This assertion is similarly echoed by the pagan author of the Asclepius, who is occasionally associated with Trismegistus. [12]

Pythagoras reportedly journeyed through Asia, Africa, and Europe, where he underwent initiation into multiple priesthoods. This learned philosopher cultivated a profound understanding across various disciplines, particularly in geometry, or what is akin to Masonry.

Among his contributions in this realm was the formulation of numerous problems and theorems, notably the celebrated Euclid’s 47th problem—upon its discovery, the moment was commemorated with a hecatomb (100 cattle) sacrifice.

What remains lesser-known is Pythagoras’ utilization of this symbol to represent the Monad.

For the Pythagoreans, the production of number sequences held significance not only in the realm of geometry but also in cosmogony. According to Diogenes Laërtius, the monad gave rise to the dyad, which led to the creation of numbers. From numbers emerged points, followed by lines, two-dimensional entities, three-dimensional entities, and bodies, eventually culminating in the formation of the four elements: earth, water, fire, and air, which serve as the foundational building blocks of our world.

To Pythagoras, the Monad embodied the genesis point of creation, encapsulating the concept of the Supreme Being, divinity, or the entirety of existence. It symbolized a notion of cosmic consciousness, an awareness that observes and learns from the intricate interplay between the micro and macrocosms. [13]

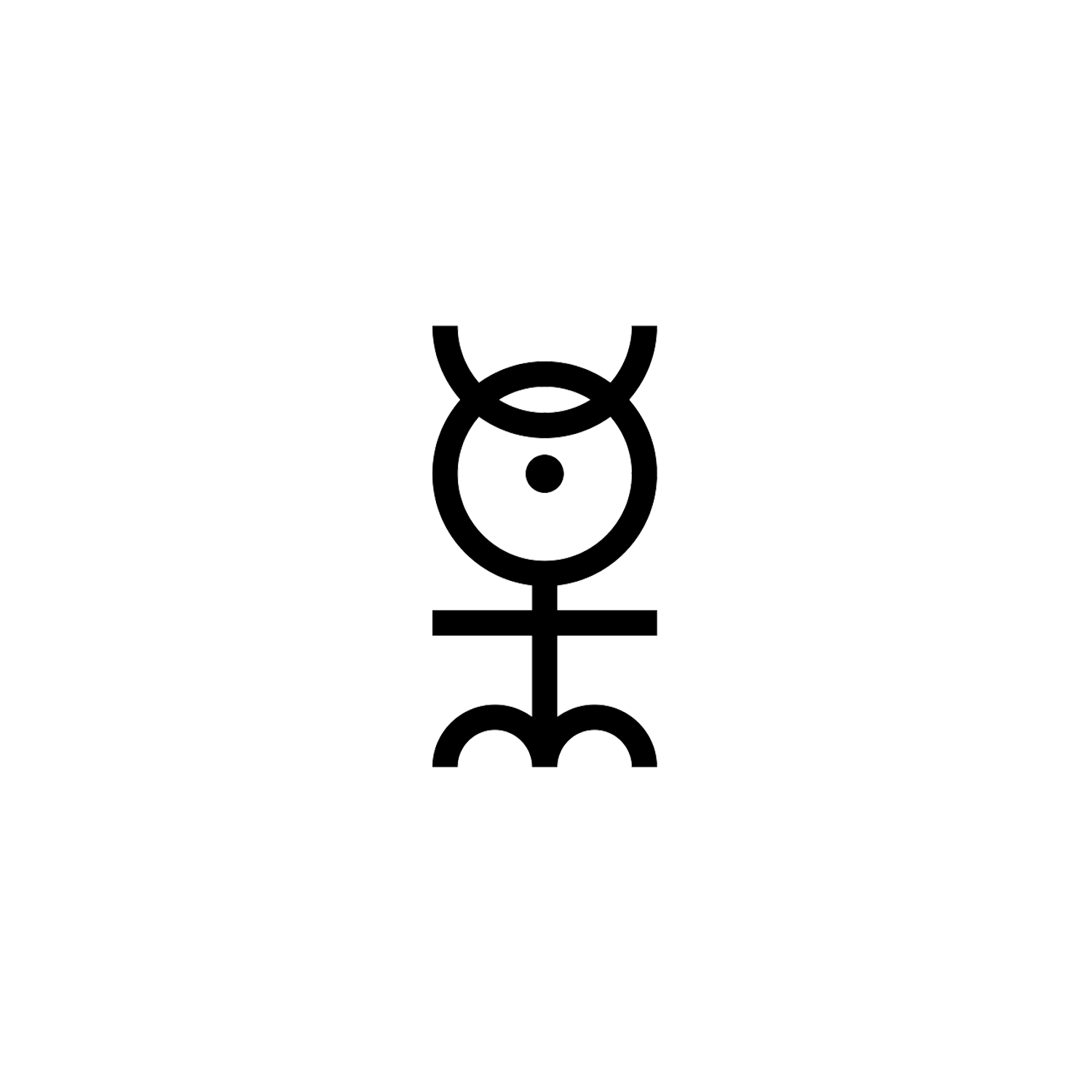

The Hieroglyphic Monad, also known as Monas Hieroglyphica, is a work authored by John Dee, the Elizabethan magus and court astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I of England.

Published in Antwerp in 1564, it serves as an exploration of the interpretation of an esoteric symbol devised by Dee himself.

The circumpunct is the center part of the head of The Hieroglyphic Monad. John Dee conceived the Monad as a comprehensive representation of mystical and esoteric principles.

This intricate symbol aimed to depict the interconnectedness of existence, drawing inspiration from astrological and planetary influences. Dee attributed to it the essence of alchemical metamorphosis and spiritual evolution.

Through contemplation of the Monad, he sought to access concealed wisdom regarding the cosmos, transcending linguistic limitations and uncovering profound truths. Ultimately, Dee aimed to encapsulate his holistic worldview, merging elements of astrology, alchemy, mysticism, and metaphysics.[14]

The glyph was adopted by the Rosicrucians and appears on a page of the Rosicrucian manifesto Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz (1616).

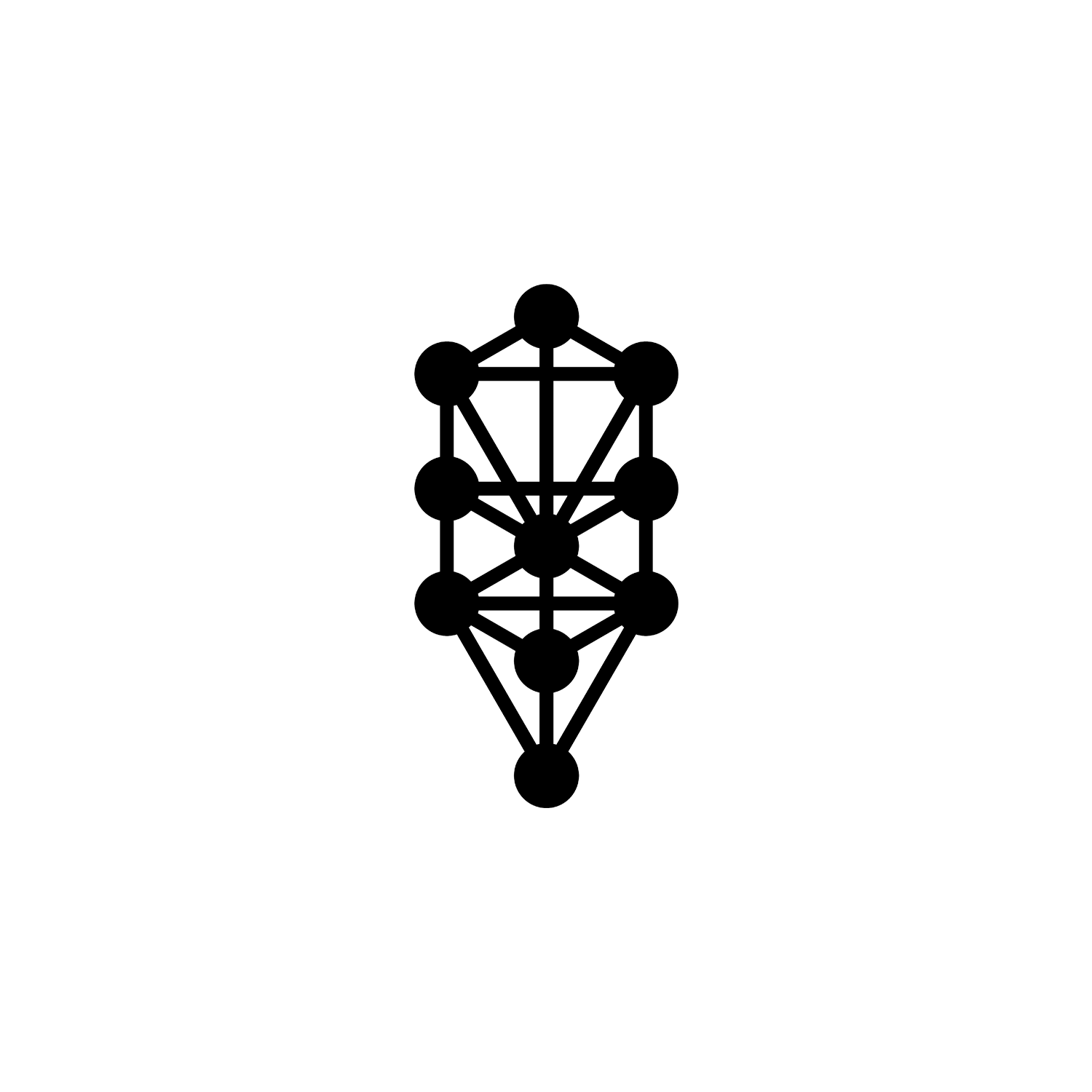

Kether and the Kabbalah

This idea of the Monad finds resonance with the concept of Kether (also spelled Keter), the highest sephirot on the Tree of Life in Kabbalah.

The initial Sephirah is designated as the Crown due to its association with the regal adornment worn atop the head. This designation signifies concepts that surpass the cognitive capacity of the mind’s understanding. In contrast, the remaining Sephirot are likened to the body, beginning with the head and progressing downwards towards action. However, the king’s crown rests above the head, symbolically linking the abstract and intangible concept of “monarchy” with the tangible and corporeal head of the ruler.

This initial Sefirah symbolizes the primal impulses of intention within the Ein Soph (Limitless Light, Infinity), or the emergence of desire to manifest into the diverse realms of existence. Yet, in this aspect, while it embodies all potentiality for manifestation, it itself contains no manifested content, hence it is referred to as ‘Nothing’, ‘The Hidden Light’, or ‘The air that cannot be grasped’. As the impulse for the world’s creation, Keter represents absolute compassion.

The divine name associated with Keter is Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh (Hebrew: אהיה אשר אהיה), the appellation through which God revealed himself to Moses from the burning bush.

As Kether is the first emanation, the Zohar makes it clear that “the supernal crown (keter elyon) is the crown of kingdom (keter malchut).” Meaning that the first, highest emanation of the Divine- Kether is linked to the last Malkhut, a concept which was summarized by Hermes Trismegistus: “As above, so below; as below, so above.”[15]

It is probably not an accident that the name of God is revealed in Exodus 3:14.[16] Pi is defined as the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. It is most commonly rounded to 3.14, although its decimal representation never ends nor does it settle into a permanently repeating pattern. As God is infinite and eternal, so is the numeric representation of Pi.

Although Keter is the highest Sefirah within its realm, it receives influence from the Malkuth Sefirah of the domain above it (refer to Sephirot). The uppermost Keter stands above all other Sefirot, although it is below Or Ein Soph, which serves as the source of all Sefirot.

In The Mystical Qabalah Dion Fortune describes Keter as pure consciousness, beyond all categories, timeless, a point that crystallises out of the Ein Soph Aur (Limitless Light, Infinity), and commences the process of emanation that ends in Malkuth.

The Sun

Egyptian hieroglyphs have a large inventory of solar symbolism because of the central position of solar deities (Ra, Horus, Aten etc.) in ancient Egyptian religion. The main logogram used for the Sun is the circumpunct.[17]

The ancient Egyptian Sun hieroglyph is Gardiner sign listed no. N5 for the sun-disc; it is also one of the hieroglyphs that refers to the god Ra. That is, the circumpunct.

The Self

The circled dot is the symbol for the Self in Jungian psychology.

Historically, the Self, according to Carl Jung, signifies the unification of consciousness and unconsciousness in a person, and representing the psyche as a whole.[18] It is realized as the product of individuation, which in his view is the process of integrating various aspects of one’s personality. For Jung, the Self is an encompassing whole which acts as a container. It could be symbolized by a circle, a square, or a mandala.[19][20]

In this context the central dot represents the Ego whereas the Self can be said to consist of the whole with the centred dot.

Jung considered that from birth every individual has an original sense of wholeness—of the Self—but that with development a separate ego-consciousness crystallizes out of the original feeling of unity.[21]

This process of ego-differentiation provides the task of the first half of one’s life-course, though Jungians also saw psychic health as depending on a periodic return to the sense of Self, something facilitated by the use of myths, initiation ceremonies, and rites of passage.[21]

Other uses

It is an icon used to designate the center of pressure. The musical symbol for tempus perfectum cum prolatione perfecta, a Mensuration sign.

In Europe it is used to designate the city center area. In geometry it is often used as the symbol for a circle, as well as an operator in mathematics in general (Hadamard product).

In modern times you could potentially mistake it for the trademark of retail-giant Target.

Conclusion

The circumpunct, also known as the circled dot or circle with a dot in the center, is a symbol that consists of a circle with a single point or dot positioned at its center. This symbol has been used across various cultures and traditions throughout history and holds diverse meanings depending on the context in which it is used.

In some interpretations, the circumpunct symbolizes unity or completeness, with the circle representing wholeness or the infinite and the dot symbolizing a central point or focus. It is often associated with concepts such as the divine, the cosmos, or the self.

Additionally, the circumpunct has been linked to symbolism related to the sun, enlightenment, or the moment of conception (fertilization of the egg by semen). In alchemy it represents gold, aside from that it may also represent the philosopher’s stone or the goal of spiritual or physical transformation.

Other symbols, such as The All Seeing Eye, The Hieroglyphic Monad and Nazar are directly related to it.

Overall, the circumpunct is a symbol as old as humanity, carrying various meanings depending on cultural, religious, or philosophical contexts, often representing concepts of unity, wholeness, or spiritual enlightenment.

[1] Periodic Table: Alchemy. Royal Society of Chemistry

[2] Epperson, Kristin. "Circumpunct" (2011), Virginia Commonwealth University.

[3] Khanna, Madhu (1979). Yantra: The Tantric Symbol Of Cosmic Unity. Thames and Hudson.

[4] Ranganathananda, Swami (1991). Human Being in Depth: A Scientific Approach to Religion. SUNY Press. p. 21. ISBN 0791406792.

[5] Shakya, Milan (2000). "Basic Concepts of Mandala". Voices of History. 15 (1): 81–87. doi:10.3126/voh.v15i1.70

[6] Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm, Freiherr von (2005). Discourse on metaphysics, and the monadology. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486443102.

[7] Hall, Manly P. "Lectures on Ancient Philosophy" (1929). academia.edu

[8] Encyclopedia Masonica, "Dedication of a Lodge". universalfreemasonry.org

[9] Joseph Needham. "Science & Civilisation in China: Chemistry and chemical technology. Spagyrical discovery and invention: magisteries of gold and immortality." Cambridge. 1974. p. 23

[10] Kauffman, George B. "The Role of Gold In Alchemy. Part II". Department of Chemistry, California State University.

[11] Principe, Lawrence M. (2013). The Secrets of Alchemy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226103792.

[12] Gilson, Etienne (February 15, 2019). "From Scotus Eriugena to Saint Bernard". History of Christian Philosophy in the Middle Ages. Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press. p. 174,809. ISBN 9780813231952. OCLC 1080547285

[13] Hobgood, Kate. "Pythagoras and the Mystery of Numbers". University of Georgia.

[14] Campbell, A. (2012). "The reception of John Dee's Monas Hieroglyphica in early modern Italy: The case of Paolo Antonio Foscarini (c. 1562–1616)". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A. 43 (3): 519–529. Bibcode:2012SHPSA..43..519C

[15] Three Initiates (1908). The Kybalion: A Study of the Hermetic Philosophy of Ancient Egypt and Greece. Chicago: The Yogi Publication Society.

[16] Exodus 3:14

[17] Collier, Mark, and Manley, Bill, How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs, c 1998, University of California Press, 179 pp, (with a word Glossary, p 151-61: Title Egyptian-English vocabulary; also an "Answer Key", 'Key to the exercises', p 162-73) (hardcover, ISBN 0-520-21597-4)

[18] Josepf L. Henderson, "Ancient Myths and Modern Man" in C. G. Jung ed., Man and his Symbols (London 1978) p. 120

[19] Research in the social scientific study of religion. Village, Andrew, Hood, Ralph W., Jr. Leiden: BRILL. 2017. p. 74. ISBN 9789004348936. OCLC 994146016.

[20] Lawson, Thomas T. (2008). Carl Jung, Darwin of the mind. London: Karnac. p. 161. ISBN 9781849406420. OCLC 727944810.

[21] Henderson, "Myths" p. 120

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.