Pentacle

Pentacle

Commonly confused with the Pentagram.

Overview

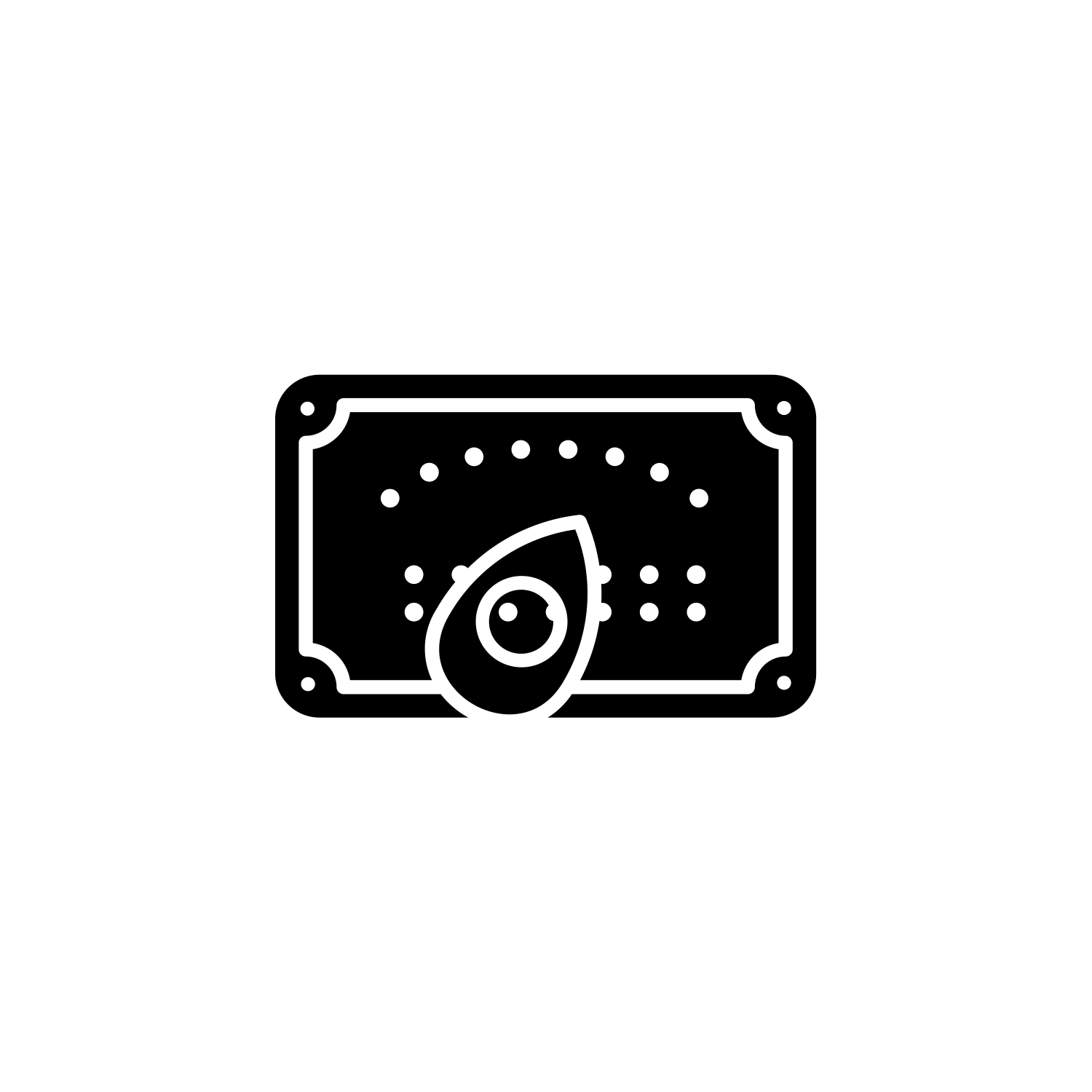

A pentacle (also spelled and pronounced as pantacle in Thelema, following Aleister Crowley, though that spelling ultimately derived from Éliphas Lévi)[1] is a talisman that is used in magical evocation, and is usually made of parchment, paper, cloth, or metal (although it can be of other materials), upon which a magical design is drawn. Symbols may also be included (sometimes on the reverse), a common one being the six-point form of the Seal of Solomon.

Pentacles may be sewn to the chest of one’s garment, or may be flat objects that hang from one’s neck or are placed flat upon the ground or altar. Pentacles are almost always shaped as disks or flat circles. In the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, though, a pentacle is placed within the triangle of evocation.

Many varieties of pentacle can be found in the grimoire called the Key of Solomon. Pentacles are also used in the neopagan magical religion called Wicca, alongside other magical tools. In the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and Wicca, pentacles symbolize the classical element earth.[2][3]

In the 1909 Rider–Waite–Smith tarot deck (the pentacles of which were designed by Arthur Edward Waite), and subsequent tarot decks that are based upon it, and in Wicca, pentacles prominently incorporate a pentagram in their design. This form of pentacle is formed upon a disk which may be used either upon an altar or as a sacred space of its own.

Some groups associate it with divinity, whereas others believe that it represents evil spirits and dark forces because it is the symbol of choice for witchcraft and magic. To further add to that confusion, there’s a misunderstanding between the ‘pentacle’ and the ‘pentagram’ symbols, and whether they represent different things or are one and the same instead.

Origin and Meaning

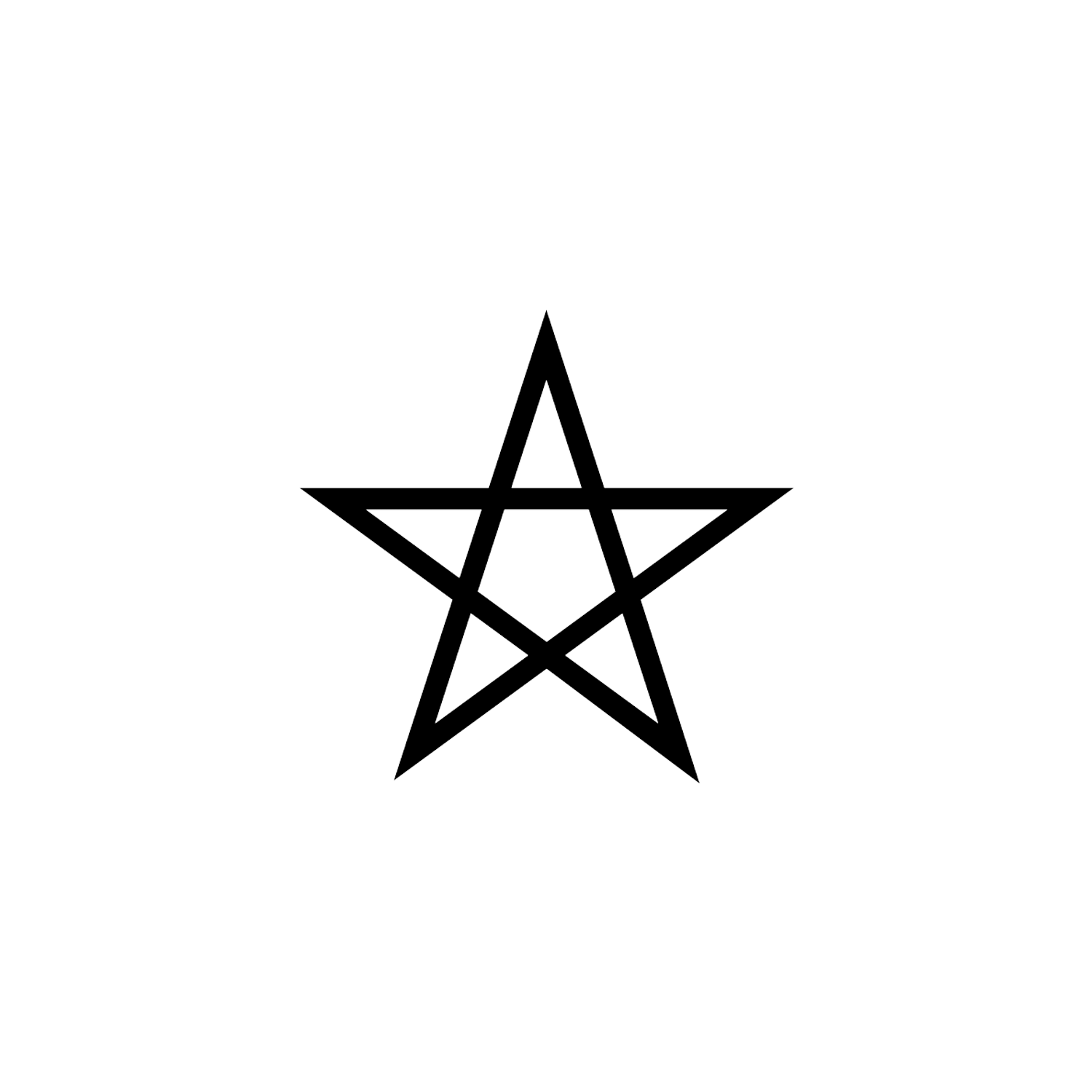

A pentagram is a five-pointed gemoetric figure— or simply a star. It is made by extending lines from the corners of a regular pentagon until they intersect each other at five different points.

The pentacle, on the other hand, is a star-shaped figure with a circle drawn around its edges.

The first documents to depict pentacles were the 1500s grimoires called the Heptameron by pseudo-Pietro d’Abano, and the Key of Solomon. In the Heptaméron, there is only one pentacle, whereas in the Key of Solomon, there are dozens of different pentacles.

The Heptameron’s pentacle is a hexagram that is embellished by patee crosses and letters, whereas the Key of Solomon’s pentacles have a very broad variety of designs, only two of which are pentagrammic. That contrasts with the later popular definitions of pentacles from the 1900s, which state that pentacles are inherently pentagrammic.

Gerald Gardner, known by some as the ‘Father of Wicca’, got his concept of pentacles in large part from the 1909 Rider–Waite–Smith tarot deck, in which the pentacles are disks that are covered with a pentagram. In Gardner’s 1949 book High Magic’s Aid and 1954 book Witchcraft Today, Gardner defined a pentacle as a “five-pointed star”, intending to mean a pentagram. In his 1959 book The Meaning of Witchcraft, Gardner defined a pentacle as a synonym of ‘pentagram‘.

There is a particular definition of ‘pentacle’ among many latter-day Wiccans: Namely, a ‘pentacle’ refers to a ‘pentagram‘ circumscribed by a circle.[3]

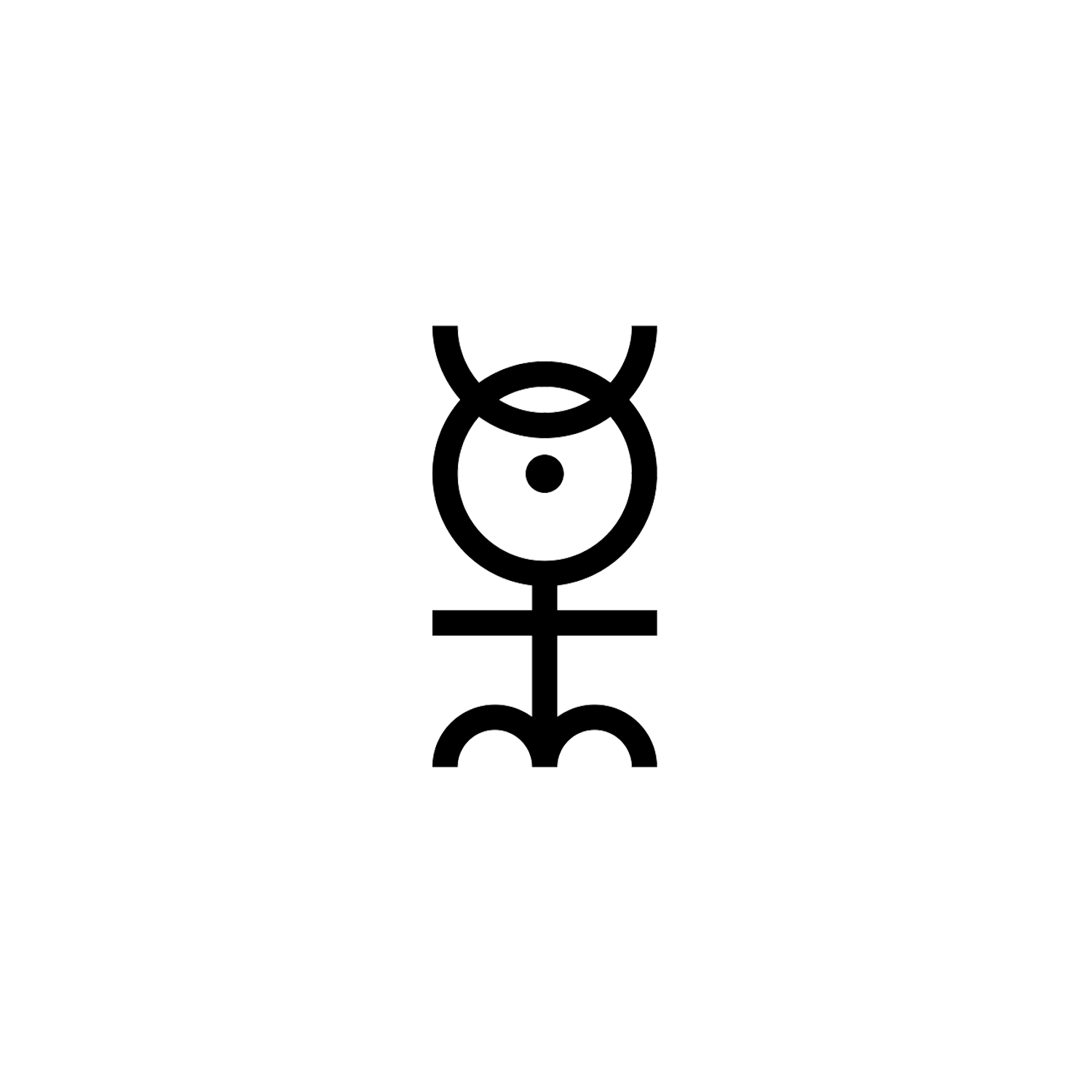

Some scholars also say that the star-shaped symbol is closely related to ancient astrology. Its five corners are said to denote the five brightest planets that were discovered a very long time ago, as they can be easily seen in the night sky by the naked eye without the aid of telescopes and other modern equipment. These are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

The word is first recorded in English usage in 1561, from earlier French use. The French word had the meaning of “talisman”. The French word is in turn from the Latinized word ‘pentaculum’ (using the Latin diminutive suffix -culum), which is in turn from the Italian word ‘pentacolo’.

The Oxford English Dictionary in earlier editions (2nd edition 1989) went on to say that “some would connect it” with the Middle French word ‘pentacol’ (1328) or ‘pendacol’ (1418), a jewel or ornament worn around the neck (from pend- hang, à to, col or cou neck).[4][5] This is the derivation the Theosophical Society employ in their glossary:

…it seems most likely that it comes through Italian and French from the root pend- “to hang”, and so is equivalent to a pendant or charm hung about the neck. From the fact that one form of pentacle was the pentagram or star-pentagon, the word itself has been connected with the Greek pente (five).[6]

The pentacle is of central importance in the evocation of spirits. A fairly typical evocation involves a series of conjurations of increasing potency, each involving the display of the pentacle.[7]

Once the spirit has appeared and been constrained, the pentacle is covered again, but is uncovered whenever demands are made of the spirit or when it is compelled to depart.

In the Golden Dawn system, the pentacles are not suspended from the neck, but wrapped in a cloth covering. Instead of wearing a pentacle, the magician wears a lamen fastened to their breast.

In the occult

Pentacles, despite the sound of the word, often had no connotation of “five” in the old magical texts, but were, rather, magical talismans inscribed with any symbol or character.

When they incorporated star-shaped figures, these were more often hexagrams than pentagrams. Pentacles showing a great variety of shapes and images appear in the old magical grimoires, such as the Key of Solomon; as Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa summarises it, their use was to “fore-know all future things, & command whole nature, have power over devils, and Angels, and do miracles.” Agrippa attributes Moses’ feats of magic in part to his knowledge of various pentacles.[8]

The Key of Solomon is divided into two books. It describes the necessary drawings to prepare each “experiment” or, in more modern language, magical operations.

Unlike later grimoires such as the Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (16th century) or the Lemegeton (17th century), the Key of Solomon does not mention the signature of the 72 spirits constrained by King Solomon in a bronze vessel. As in most medieval grimoires, all magical operations are ostensibly performed through the power of God, to whom all the invocations are addressed. Before any of these operations (termed “experiments”), the operator must confess his sins and purge himself of evil, invoking the protection of God.

Elaborate preparations are necessary, and each of the numerous items used in the operator’s “experiments” must be constructed of the appropriate materials obtained in the prescribed manner, at the appropriate astrological time, marked with a specific set of magical symbols, and blessed with its own specific words.

All substances needed for the magic drawings and amulets are detailed, as well as the means to purify and prepare them. Many of the symbols incorporate the Transitus Fluvii occult alphabet.

In the Golden Dawn magical system, the Earth Pentacle is one of four elemental “weapons” or tools of an Adept. These weapons are “symbolical representations of the forces employed for the manifestation of the inner self, the elements required for the incarnation of the divine.”[9]

Other pentacles for the evocation of spirits are also employed in the Golden Dawn system; these are engraved with the name and sigil of the spirit to be invoked, inside three concentric circles, having painted on their reverse a circle and cross like a celtic cross.[10]

According to Aleister Crowley’s instructions for the A∴A∴, the pentacle is a disc of wax, gold, silver-gilt or Electrum Magicum, eight inches diameter and half an inch thick; the Neophyte should “by his understanding and ingenium devise a symbol to represent the Universe”, and engrave this on the disc.[11]

“There is, therefore, nothing movable or immovable under the whole firmament of heaven which is not included in this pantacle, though it be but “eight inches in diameter, and in thickness half an inch.” Fire is not matter at all; water is a combination of elements; air almost entirely a mixture of elements; earth contains all both in admixture and in combination. So must it be with this Pantacle, the symbol of earth.”[12]

Much like conventional playing cards, the Minor Arcana of the tarot are divided into four suits. The suit names have evolved over time, and based on the innovation of Éliphas Lévi, contemporary English-language writers on tarot divination often prefer “pentacles” for the suite of coins.

The 1909 Rider–Waite–Smith tarot deck was the first to use an actual suit of pentacles, where Arthur Edward Waite designed the pentacles as golden disks with a pentagram on them. The influence of that deck resulted in widespread use of the pentacle symbol, particularly among Wiccans.

The Rider–Waite Tarot is a widely popular deck for tarot card reading.[13][14] It is also known as the Waite–Smith,[15] Rider–Waite–Smith,[16][17] or Rider Tarot.[18] Based on the instructions of academic and mystic A. E. Waite and illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith, both members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the cards were originally published by the Rider Company in 1909. The deck has been published in numerous editions and inspired a wide array of variants and imitations.[19][20] It is estimated that more than 100 million copies of the deck exist in more than 20 countries.[21]

Conclusion

In modern times the pentacle is most often associated with Neo-Pagan religions, especially Wicca. It is often depicted as a pentagram pointing upward, enclosed in a circle. In these traditions the five points often represent the five elements of air, fire, water, earth, and spirit.

For Wiccans the pentagram may also symbolize masculine and feminine, or the Triple Goddess (three points) and the Horned God (two points). Many Neo-Pagans consider the pentagram a symbol of protection and may use it to invoke or banish spirits. The pentacle is the approved symbol of the Wiccan faith to be used on headstones in U.S. government cemeteries.

For more information on the Pentagram, the meanings of which overlap with and extend the ones of the Pentacle, read the separate article for the symbol.

[1] Crowley, Aleister (1991). "Liber CLXV: A Master of the Temple". The Equinox of the Gods. New Falcon Publication. ISBN 978-1561840281. "The Pantacle of Frater V. I. O."

[2] Farrar, Janet; Farrar, Stewart (1996) [1981]. "The Witches' Way". A Witches' Bible. Custer, Washington: Phoenix. ISBN 0-919345-92-1.

[3] Guiley, Rosemary (1989). The Encyclopedia of Witches and Witchcraft. New York: Facts on File. pp. 122–124. ISBN 0-8160-2268-2.

[4] "Pentacle". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

[5] Godefroy, Frédéric (1881–1902). Dictionnaire de l'ancienne langue française et de tous ses dialectes du IXe au XVe siècle. Vol. 6. Paris: F. Vieweg. p. 88. OCLC 1034921.

[6] de Purucker, Gottfried, ed. (1999). "Pa-Peq". Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary. Theosophical University Press. ISBN 978-1-55700-141-2.

[7] The Key of Solomon. Translated by MacGregor Mathers, S. L.

[8] Agrippa, Heinrich Cornelius (1651) [1533]. "Of Occult Philosophy, Book 3, Part 5". Translated by French, John.

[9] Regardie, Israel (2003). The Golden Dawn. St. Paul, Minnesota: Llewellyn. p. 47. ISBN 0-87542-663-8. Volume I, section 94.

[10] Regardie, Israel (2003). "Z.2: Magical Formulae". The Golden Dawn. St. Paul, Minnesota: Llewellyn. p. 380. ISBN 0-87542-663-8. Volume III, section 159.

[11] Crowley, Aleister. "The Pantacle". Liber CDXII: Liber A vel Armorum. A∴A∴.

[12] Crowley, Aleister (1997). "The Pantacle". Magick: Book 4, Liber ABA. York Beach, Maine: S. Weiser. p. 95. ISBN 0-87728-919-0.

[13] Giles, Cynthia (1994). The Tarot: History, Mystery, and Lore. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 46. ISBN 0-671-89101-4.

[14] Visions and Prophecies. Alexandria, Virginia: Time–Life Books. 1988. p. 142.

[15] Katz, Marcus; Goodwin, Tali (2015). Secrets of the Waite–Smith Tarot. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 978-0-7387-4119-2.

[16] Michelsen, Teresa (2005). The Complete Tarot Reader: Everything You Need to Know from Start to Finish. Llewellyn Publications. p. 105. ISBN 0-7387-0434-2.

[17] Graham, Sasha (2018). Llewellyn's Complete Book of the Rider–Waite–Smith Tarot. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 978-0-7387-5319-5.

[18] Michelsen, Teresa (2005). The Complete Tarot Reader: Everything You Need to Know from Start to Finish. Llewellyn Publications. p. 105. ISBN 0-7387-0434-2.

[19] Kaplan, Stuart R. (2018). Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story. Stamford, Connecticut: U.S. Game Systems. p. 371. ISBN 978-1-57281-912-2.

[20] Dean, Liz (2015). The Ultimate Guide to Tarot: A Beginner's Guide to the Cards, Spreads, and Revealing the Mystery of the Tarot. Beverly, Massachusetts: Fair Winds Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-59233-657-9.

[21] Ray, Sharmistha (23 March 2019). "Reviving a Forgotten Artist of the Occult". Hyperallergic. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.