Crown of Thorns

Crown of Thorns

Synonymous with martyrdom.

Overview

The crown of thorns is arguably one of the most iconic images of Christ’s crucifixion. Perhaps more than any form of physical suffering He endured, the crown Jesus bore signifies Christ’s ultimate humility in trading His heavenly crown for a lowly crown of suffering and shame.

Crown of Thorns, wreath of thorns that was placed on the head of Jesus Christ at his crucifixion, whereby the Roman soldiers mocked his title “King of the Jews.” The relic purported to be the Crown of Thorns was transferred from Jerusalem to Constantinople by 1063. The French king Louis IX (St. Louis) took the relic to Paris about 1238 and had the Sainte-Chapelle built (1242–48) to house it.

The thornless remains are kept in the treasury of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris; they survived a devastating fire in April 2019 that destroyed the church’s roof and spire.

Origin and Meaning

According to the New Testament, a woven crown of thorns (Greek: στέφανος ἐξ ἀκανθῶν, translit. stephanos ex akanthōn or ἀκάνθινος στέφανος, akanthinos stephanos) was placed on the head of Jesus during the events leading up to his crucifixion. It was one of the instruments of the Passion, employed by Jesus’ captors both to cause him pain and to mock his claim of authority.

It is mentioned in the gospels of Matthew (Matthew 27:29),[1] Mark (Mark 15:17)[2] and John (John 19:2, 19:5),[3] and is often alluded to by the early Church Fathers, such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen and others, along with being referenced in the apocryphal Gospel of Peter.[4]

Since at least around the year 400 AD, a relic believed by many to be the crown of thorns has been venerated. In 1238, the Latin Emperor Baldwin II of Constantinople yielded the relic to French King Louis IX. It was kept in the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris until 15 April 2019, when it was rescued from a fire and moved to the Louvre Museum.[6]

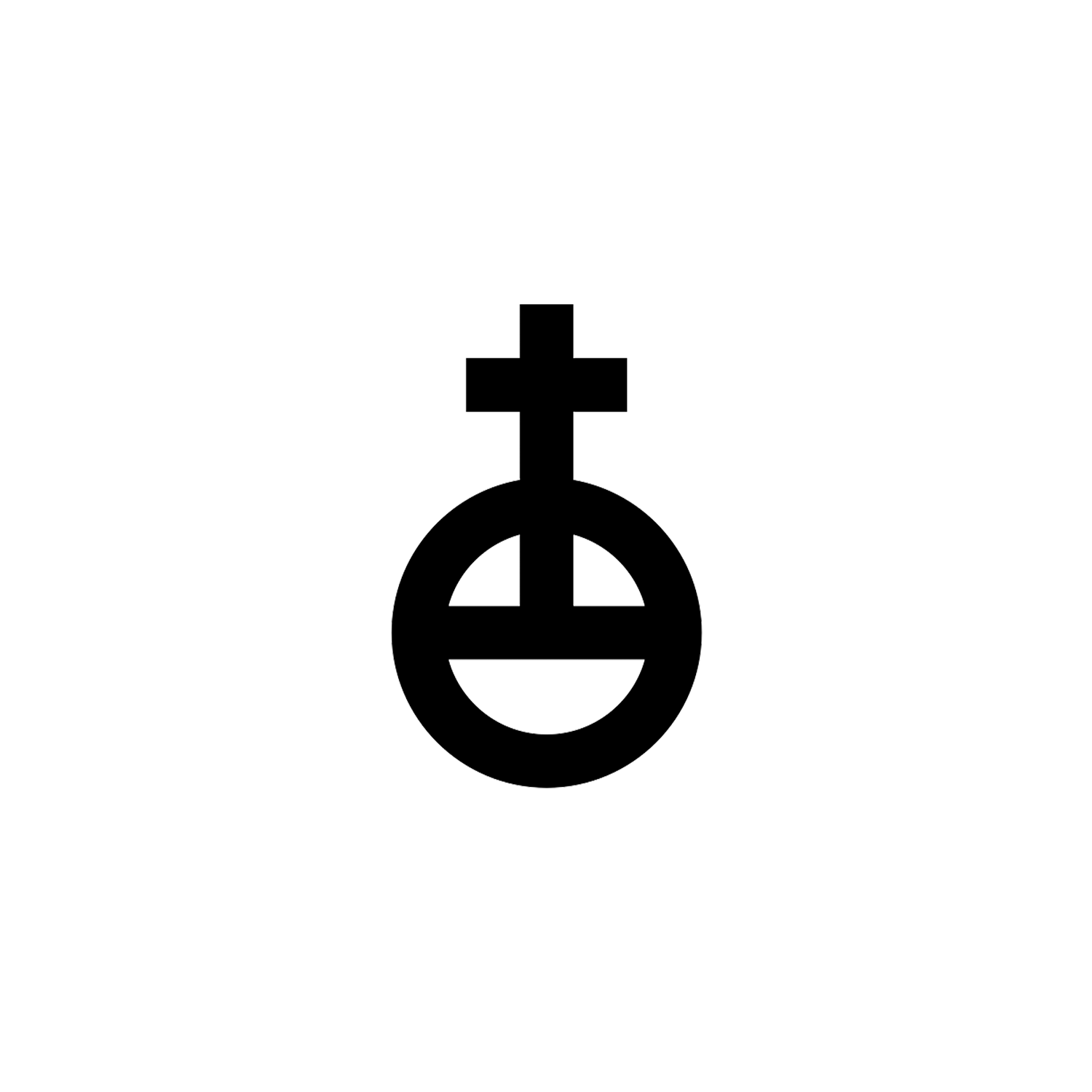

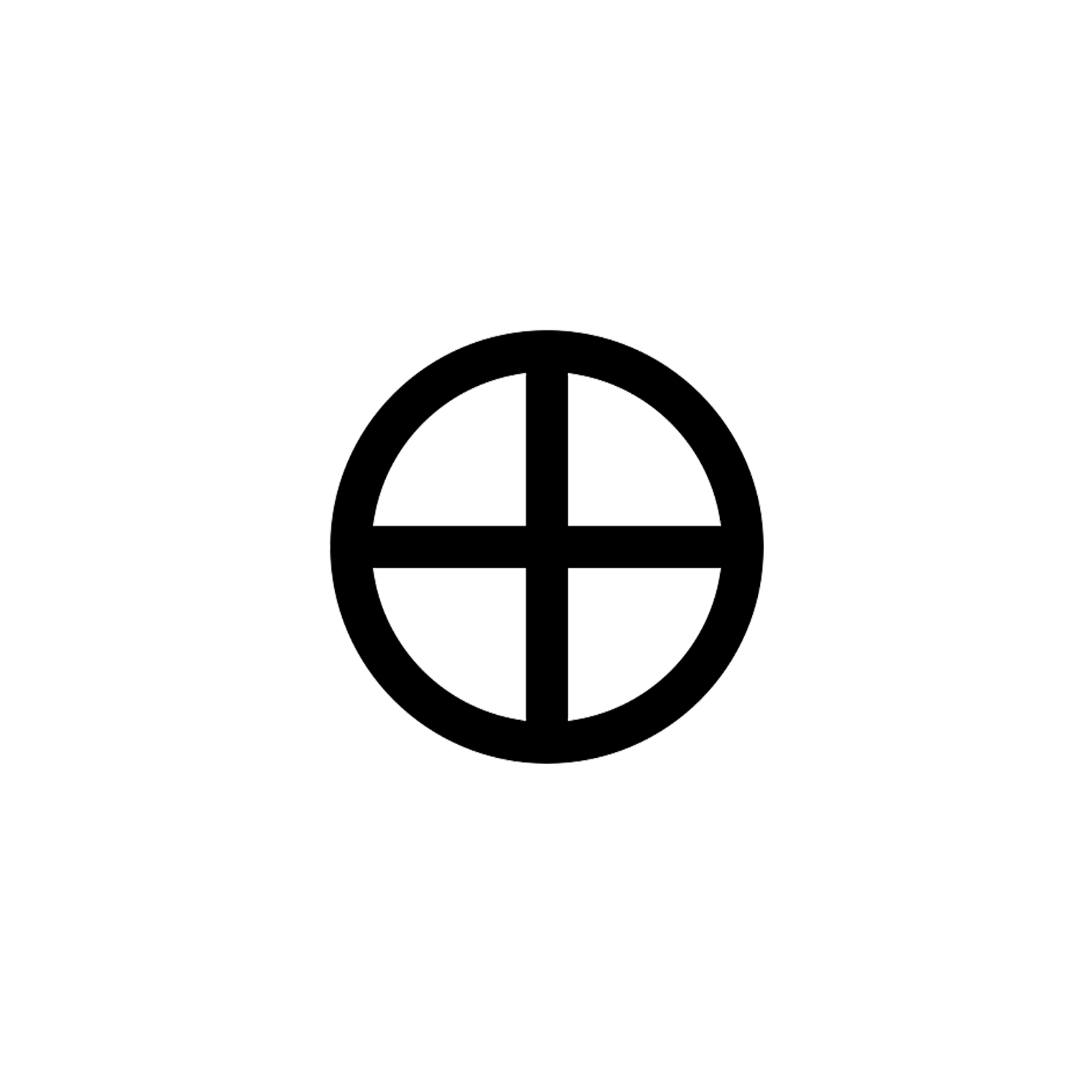

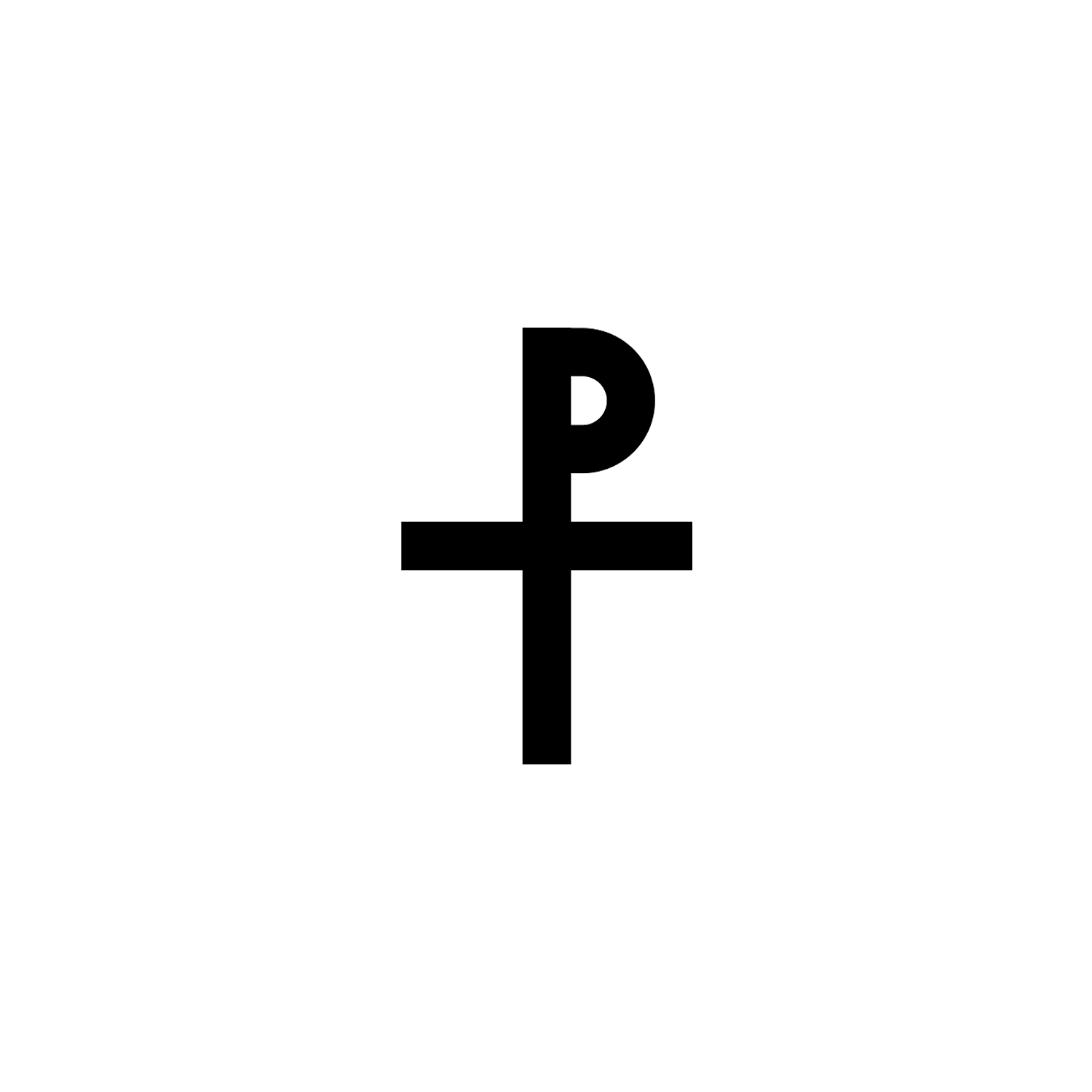

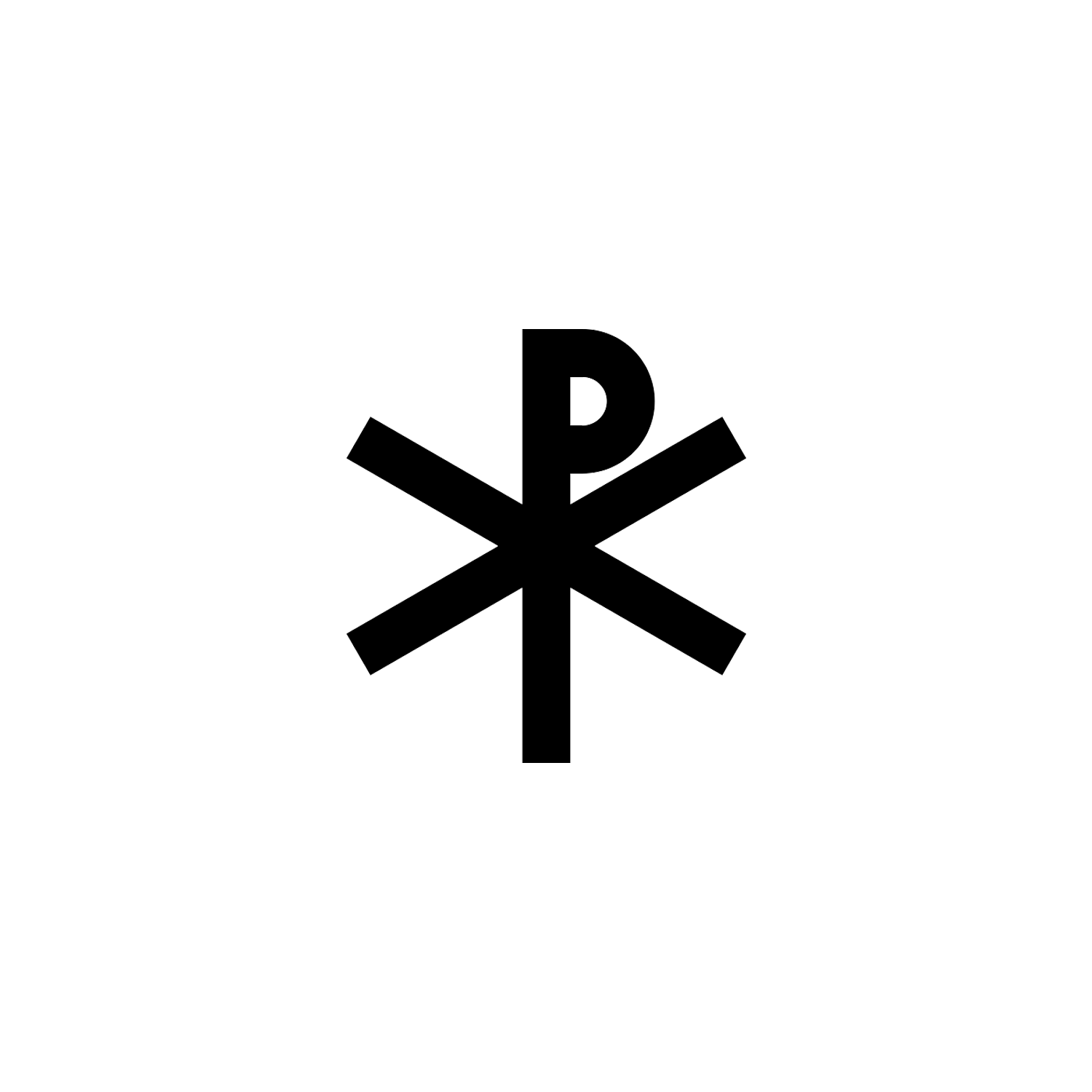

The appearance of the crown of thorns in art, notably upon the head of Christ in representations of the Crucifixion or the subject Ecce Homo, arises after the time of St. Louis and the building of the Sainte-Chapelle. The Catholic Encyclopedia reported that some archaeologists had professed to discover a figure of the crown of thorns in the circle which sometimes surrounds the chi-rho emblem on early Christian sarcophagi, but the compilers considered that it seemed to be quite as probable that this was only meant for a laurel wreath.

Catholic missionaries likened several parts of the Passiflora plant to elements of the Passion: the flower’s radial filaments, which can number more than a hundred and vary from flower to flower, represent the crown of thorns.[7] Carnations symbolize the passion as they represent the crown of thorns.

The image of the crown of thorns is often used symbolically to contrast with earthly monarchical crowns.

In the symbolism of King Charles the Martyr, the executed English King Charles I is depicted putting aside his earthly crown to take up the crown of thorns, as in William Marshall’s print Eikon Basilike.

This contrast appears elsewhere in art, for example in Frank Dicksee’s painting The Two Crowns.[8]

The Relic

The three Biblical gospels that mention the crown of thorns do not say what happened to it after the crucifixion. The oldest known mention of the crown already being adored as a relic was made by Paulinus of Nola, writing after 409,[9] who refers to the crown as a relic that was adored by the faithful (Epistle Macarius in Migne, Patrologia Latina, LXI, 407). Cassiodorus (c. 570) speaks of the crown of thorns among other relics which were “the glory” of the city of Jerusalem. “There”, he says, “we may behold the thorny crown, which was only set upon the head of Our Redeemer in order that all the thorns of the world might be gathered together and broken” (Migne, LXX, 621).

When Gregory of Tours in De gloria martyri[10] avers that the thorns in the crown still looked green, a freshness which was miraculously renewed each day, he does not much strengthen the historical authenticity of a relic he had not seen, but the Breviary of Jerusalem[11] :16 (a short text dated to about 530 AD),[11]: iv and the itinerary of Antoninus of Piacenza (6th century)[12]: 18 clearly state that the crown of thorns was then shown in the “Basilica of Mount Zion,” although there is uncertainty about the actual site to which the authors refer.[12]: 42 et seq. From these fragments of evidence and others of later date (the “Pilgrimage” of the monk Bernard shows that the relic was still at Mount Zion in 870), it is shown that a purported crown of thorns was venerated at Jerusalem in the first centuries of the common era.

Some time afterwards, the crown was purportedly moved to Constantinople, then capital of the empire. Historian François de Mély supposed that the whole crown was transferred from Jerusalem to Constantinople not much before 1063. In any case, Emperor Justinian is stated to have given a thorn to Germain, Bishop of Paris, which was long preserved at Saint-Germain-des-Prés, while the Empress Irene, in 798 or 802, sent Charlemagne several thorns which were deposited by him at Aachen.

Eight of these are said to have been there at the consecration of the basilica of Aachen; the subsequent history of several of them can be traced without difficulty: four were given to Saint-Corneille of Compiègne in 877 by Charles the Bald; Hugh the Great, Duke of the Franks, sent one to the Anglo-Saxon King Athelstan in 927, on the occasion of certain marriage negotiations, and it eventually found its way to Malmesbury Abbey; another was presented to a Spanish princess about 1160; and again another was taken to Andechs Abbey in Germany in the year 1200.[13]

The Journey to France

In 1238, Baldwin II, the Latin Emperor of Constantinople, anxious to obtain support for his tottering empire, offered the crown of thorns to Louis IX of France. It was then in the hands of the Venetians as security for a great loan of 13,134 gold pieces, yet it was redeemed and conveyed to Paris where Louis IX built the Sainte-Chapelle, completed in 1248, to receive it. The relic stayed there until the French Revolution, when, after finding a home for a while in the Bibliothèque Nationale, the Concordat of 1801 restored it to the Catholic Church, and it was deposited in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris.[14]

The exact plant species used to make the crown is not confirmed. The relic that the church received was examined in the nineteenth century, and it appeared to be a twisted circlet of rushes of Juncus balticus, a plant native to maritime areas of northern Britain, the Baltic region, and Scandinavia.[15][16] The thorns preserved in various other reliquaries appeared to be Ziziphus spina-christi,[17] a plant native to Africa and Southern and Western Asia, and had allegedly been removed from the crown and kept in separate reliquaries since soon after they arrived in France.[18] New reliquaries were provided for the relic, one commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte, another, in jeweled rock crystal and more suitably Gothic, was made to the designs of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.

In 2001, when the surviving treasures from the Sainte-Chapelle were exhibited at the Louvre, the chaplet was solemnly presented every Friday at Notre-Dame. Pope John Paul II translated it personally to Sainte-Chapelle during World Youth Day. The relic can be seen only on the first Friday of every month, when it is exhibited for a special veneration Mass, as well as each Friday of Lent[19] (see also Feast of the Crown of Thorns).

Members of the Paris Fire Brigade saved the relic during the Notre-Dame de Paris fire of April 15, 2019.[20]

Purported Remnants

Prior to the Seventh Crusade, Louis IX of France bought from Baldwin II of Constantinople what was venerated as Jesus’ Crown of Thorns. It is kept in Paris to this day, in the Louvre Museum. Individual thorns were given by the French monarch to other European royals: the Holy Thorn Reliquary in the British Museum, for example, containing a single thorn, was made in the 1390s for the French prince Jean, duc de Berry, who is documented as receiving more than one thorn from Charles V and VI, his brother and nephew.[21]

Two “holy thorns” were venerated, one at St. Michael’s church in Ghent, the other at Stonyhurst College, both professing to be thorns given by Mary, Queen of Scots to Thomas Percy, 7th Earl of Northumberland.[22][23]

Conclusion

The crown of thorns is believed to have been fashioned by the Roman soldiers as a mock coronation for a lowly political prisoner (in their eyes). In the hours leading up to His crucifixion, Jesus would sit through two trials, one religious and Jewish, the other political and Roman.

Theologians agree that there was nothing standard or routine about Jesus’ arrest and being sentenced to die by crucifixion. He was an innocent man whom Pilate found no charge against (see John 19:6). But Jesus was sentenced to death because that was the reason he came to earth; so that he could save the world and make salvation possible for all peoples and nations.

[1] Matthew 27:29

[2] Mark 15:17

[4] Walter Richard (1894). The Gospel According to Peter: A Study. Longmans, Green. p. 7.

[5] Davisson, Darrell D (2004). Kleinhenz, Christopher (ed.). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 955. ISBN 9780415939294.

[6] Clicquot, Athénaïs (9 September 2019). "Notre-Dame: la couronne d'épines à nouveau présentée à la vénération des fidèles" (in French).

[7] Roger L. Hammer (6 January 2015). Everglades Wildflowers: A Field Guide to Wildflowers of the Historic Everglades, including Big Cypress, Corkscrew, and Fakahatchee Swamps. Falcon Guides. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-1-4930-1459-0.

[8] The Two Crowns

[9] Wall, J. Charles (2016). Relics from the Crucifixion: Where They Went and How They Got There. Sophia Institute Press. p. 95. ISBN 9781622823277

[10] Published in Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores Merovingenses", I, 492.

[11] The Epitome of S. Eucherius About Certain Holy Places: And the Breviary or Short Description of Jerusalem. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society. 1896.

[12] Stewart, Aubrey; Wilson, CW, eds. (1896). Of the Holy Places Visited by Antoninus Martyr (Circ. 560–570 A.D.). London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

[13] History and Authenticity of the Relic of the Crown of Thorns (2019). Mystogogy Resource Center.

[14] "France: Kissing the original Crown of Thorns worn by Jesus". Minor Sights.

[15] P.A. Stroh; T. A. Humphrey; R.J. Burkmar; O.L. Pescott; D.B. Roy; K.J. Walker (eds.). "Juncus balticus Willd". BSBI Online Plant Atlas 2020.

[16] "Juncus balticus Willd". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

[17] Cherry 2010, p. 22–23

[18] Cherry 2010, p. 22–23

[19] "France: Kissing the original Crown of Thorns". Minor Sights.

[20] ""Computer glitch" may be behind Notre Dame Cathedral fire, rector says - live updates". CBS News. 19 April 2019.

[21] Cherry 2010, p. 22–23.

[22] John Morris, Life of Father Gerard (London, 1881), pp. 126-131.

[23] Thurston, Herbert (1908). "Crown of Thorns" . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4.

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.