INRI

INRI

Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum.

Overview

The initialism INRI (Latin: Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum) represents the Latin inscription (in John 19:19 and Matthew 27:37), which in English translates to “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews”, and John 19:20 states that this was written in three languages—Hebrew, Latin, and Greek—during the crucifixion of Jesus.

Origin and Meaning

In the New Testament, Jesus was mocked as King of the Jews, both at the beginning of his life and at the end by the Romans, though Jesus rejected that title before Pilate in John 18:34. However, the chief priests correct the mockery, challenging Jesus as “King of Israel” in Matthew 27:42. In the Koine Greek of the New Testament, the mockery of King of the Jews, e.g., in John 19:3, this is written as Basileus ton Ioudaion (βασιλεὺς τῶν Ἰουδαίων).[1]

Both uses of the title lead to dramatic results in the New Testament accounts. In the account of the nativity of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, the unfamiliar foreign Biblical Magi who come from the east mistakenly call Jesus the “King of the Jews”, causing Herod the Great to order the Massacre of the Innocents. Towards the end of the accounts of all four canonical Gospels, in the narrative of the Passion of Jesus, the title “King of the Jews” leads to charges against Jesus that result in his crucifixion.[2][3]

The title “King of the Jews” is only used in the New Testament by gentiles, namely by the Magi, Pontius Pilate, and the Roman soldiers. In contrast, the Jewish leaders use the designation “King of Israel”. They use the Hebrew word “Messiah,” while ‘Christ’ is a Greek translation of the word.[4] Although the phrase “King of the Jews” is used in most English translations,[5] it has also been translated “King of the Judeans” (see Ioudaioi).[6]

In the account of the nativity of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, the Biblical Magi go to King Herod in Jerusalem and (in Matthew 2:2) ask him: “Where is he that is born King of the Jews?”[7] Herod asks the “chief priests and teachers of the law”, who tell him in Bethlehem of Judea.

The question troubles Herod who considers the title his own, and in Matthew 2:7–8 he questions the Magi about the exact time of the Star of Bethlehem’s appearance. Herod sends the Magi to Bethlehem, telling them to notify him when they find the child. After the Magi find Jesus and present their gifts, having been warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they returned to their country by a different way.

An angel appears to Joseph in a dream and warns him to take Jesus and Mary into Egypt (Matthew 2:13). When Herod realizes he has been outwitted by the Magi he gives orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who are two years old and under. (Matthew 2:16)

In the accounts of the Passion of Jesus, the title King of the Jews is used on three occasions. In the first such episode, all four Gospels state that the title was used for Jesus when he was interviewed by Pilate and that his crucifixion was based on that charge, as in Matthew 27:11, Mark 15:2, Luke 23:3 and John 18:33.[8]

The use of the terms king and kingdom and the role of the Jews in using the term king to accuse Jesus are central to the discussion between Jesus and Pilate. In Mark 15:2, Jesus responds to Pilate, “you have said so” when asked if Jesus is the King of the Jews and says nothing further. In John 18:34, he hints that the king accusation did not originate with Pilate but with “others” and, in John 18:36, he states: “My kingdom is not of this world”. However, Jesus does not directly deny being the King of the Jews.[9][10]

The Story

In the New Testament, Pilate writes “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews” as a sign to be affixed to the cross of Jesus. John 19:21 states that the Jews told Pilate: “Do not write King of the Jews” but instead write that Jesus had merely claimed that title, but Pilate wrote it anyway.[11] Pilate’s response to the protest is recorded by John: “What I have written, I have written.”

After the trial by Pilate and after the flagellation of Christ episode, the soldiers mock Jesus as the King of Jews by putting a purple robe (that signifies royal status) on him, place a Crown of Thorns on his head, and beat and mistreat him in Matthew 27:29–30, Mark 15:17–19 and John 19:2–3.[12]

The continued reliance on the use of the term king by the Judeans to press charges against Jesus is a key element of the final decision to crucify him.[13] In John 19:12 Pilate seeks to release Jesus, but the Jews object, saying: “If thou release this man, thou art not Caesar’s friend: every one that maketh himself a king speaketh against Caesar”, bringing the power of Caesar to the forefront of the discussion.[13] In John 19:12, the Jews then cry out: “Crucify him! … We have no king but Caesar.”

The use of the term “King of the Jews” by the early Church after the death of Jesus was thus not without risk, for this term could have opened them to prosecution as followers of Jesus, who was accused of possible rebellion against Rome.[13]

The final use of the title only appears in Luke 23:36–37. Here, after Jesus has carried the cross to Calvary and has been nailed to the cross, the soldiers look up on him on the cross, mock him, offer him vinegar and say: “If thou art the King of the Jews, save thyself.” In the parallel account in Matthew 27:42, the Jewish priests mock Jesus as “King of Israel”, saying: “He is the King of Israel; let him now come down from the cross, and we will believe in him.”

INRI and INBI

The initialism INRI represents the Latin inscription IESVS NAZARENVS REX IVDÆORVM (Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum), which in English translates to “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews” (John 19:19).[14] John 19:20 states that this was written in three languages – Hebrew,[15] Latin and Greek – and was put on the cross of Jesus.

The Greek version of the initialism reads ΙΝΒΙ, representing Ἰησοῦς ὁ Ναζωραῖος ὁ βασιλεύς τῶν Ἰουδαίων (Iēsoûs ho Nazōraîos ho basileús tôn Ioudaíōn).[16]

Devotional enthusiasm greeted the discovery by Pedro González de Mendoza in 1492 of what was acclaimed as the actual tablet, said to have been brought to Rome by Saint Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine.[17][18]

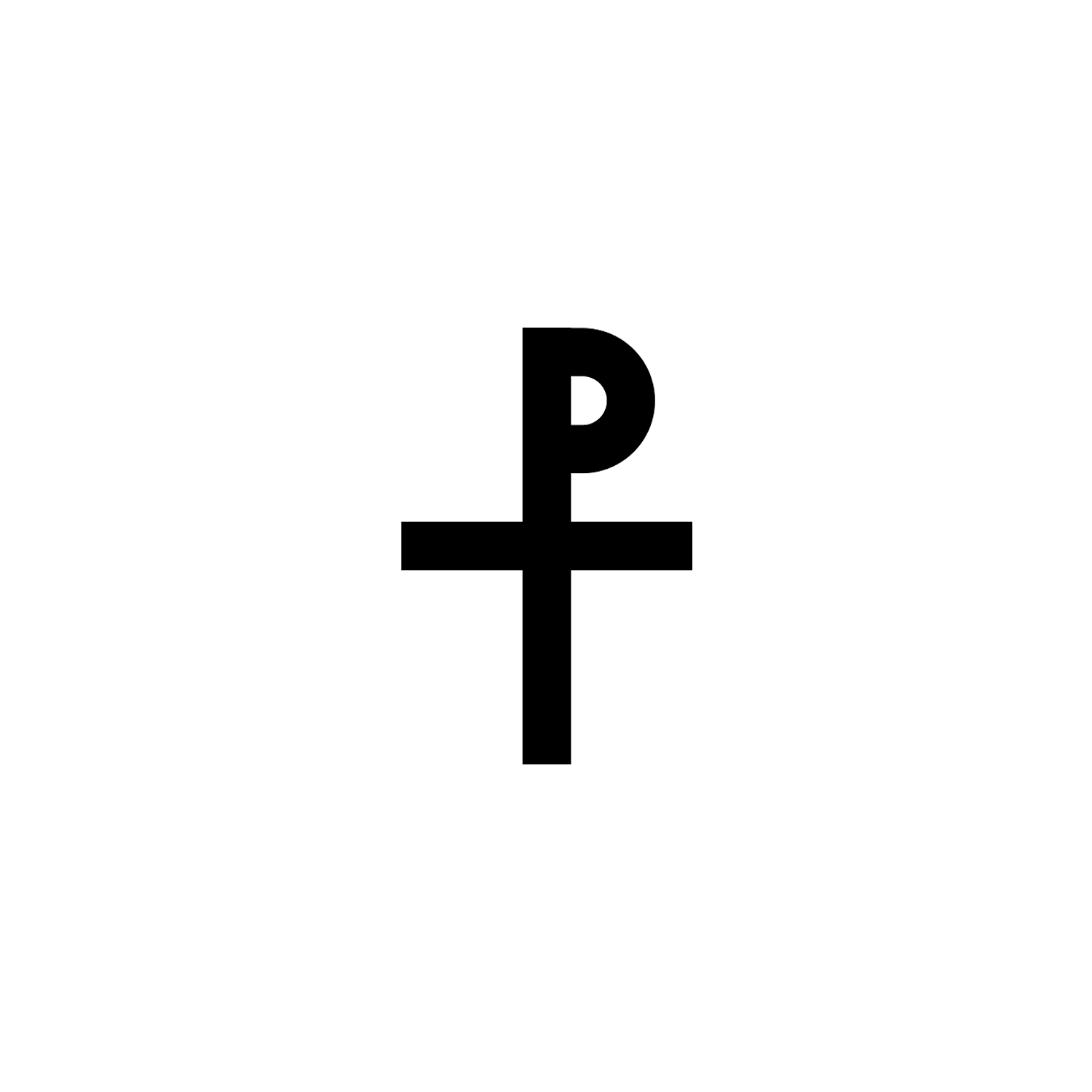

In Western Christianity, most crucifixes and many depictions of the crucifixion of Jesus include a plaque or parchment placed above his head, called a titulus, or title, bearing only the Latin letters INRI, occasionally carved directly into the cross and usually just above the head of Jesus. The initialism INRI (as opposed to the full inscription) was in use by the 10th century (Gero Cross, Cologne, ca. 970).

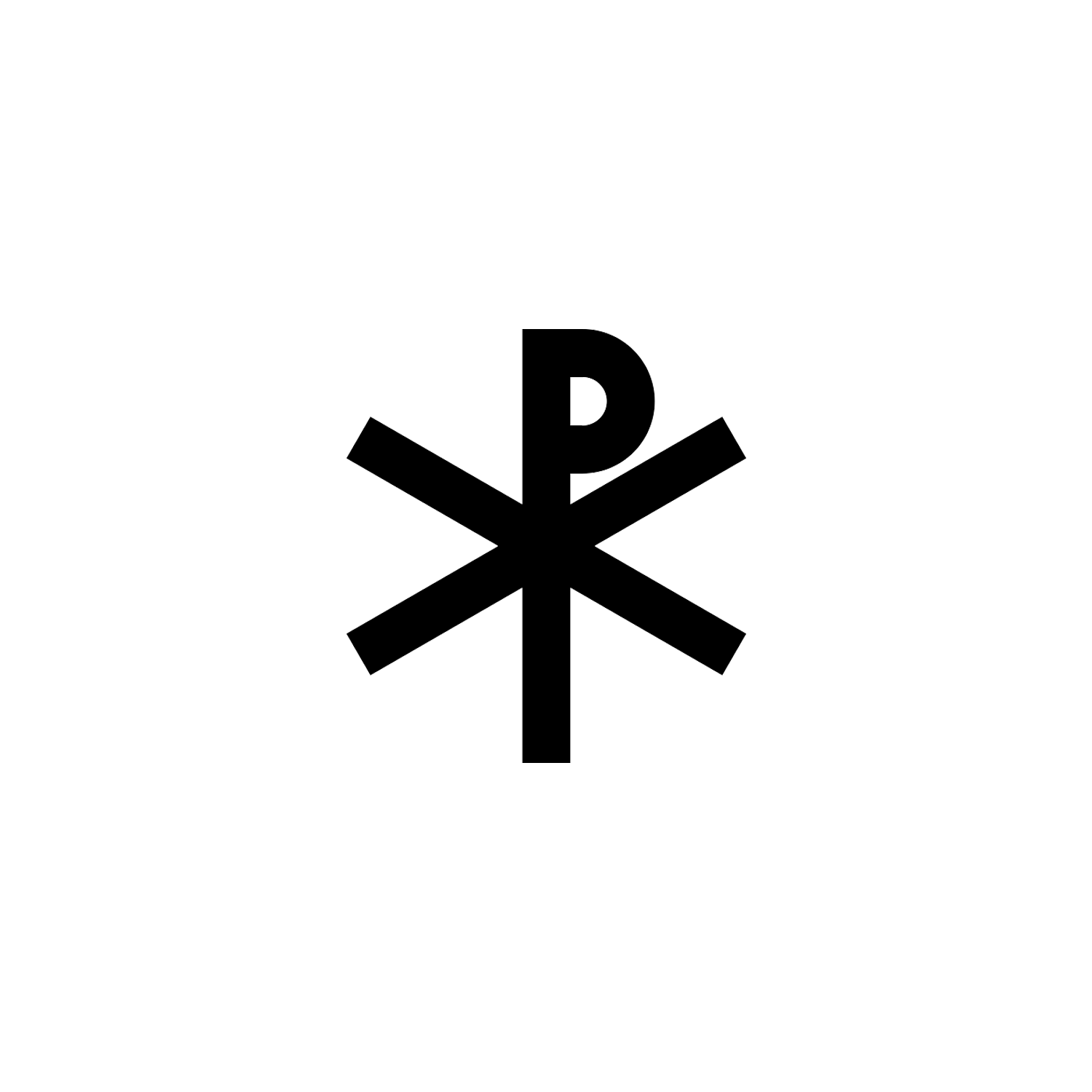

In Eastern Christianity, both the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Eastern Catholic particular churches sui iuris use the Greek letters ΙΝΒΙ, based on the Greek version of the inscription Ἰησοῦς ὁ Ναζωραῖος ὁ βασιλεύς τῶν Ἰουδαίων. Some representations change the title to “ΙΝΒΚ,” ὁ βασιλεύς τοῦ κόσμου (ho Basileùs toû kósmou, “The King of the World”), or to ὁ βασιλεύς τῆς Δόξης (ho Basileùs tês Dóxēs, “The King of Glory”),[19][20] not implying that this was really what was written but reflecting the tradition that icons depict the spiritual reality rather than the physical reality.

Other uses

The initials INRI have been reinterpreted with other expansions (backronyms). In an 1825 book on Freemasonry, Marcello Reghellini de Schio alleged that Rosicrucians gave “INRI” alchemical meanings:[21]

1. Latin Igne Natura Renovatur Integra (“by fire, nature renews itself”); other sources have Igne Natura Renovando Integrat

2. Latin Igne Nitrum Roris Invenitur (“the nitre of dew is found by fire”)

3. Hebrew ימים, נור, רוח, יבשת (Yammīm, Nūr, Rūaḥ, Yabešet, “water, fire, wind, earth” — the four elements)

Later writers have attributed these to Freemasonry, Hermeticism, or neo-paganism. Aleister Crowley’s The Temple of Solomon the King includes a discussion of Augoeides, supposedly written by “Frater P.” of the A∴A∴:[22]

For since Intra Nobis Regnum deI [footnote in original: I.N.R.I.], all things are in Ourself, and all Spiritual Experience is a more of less complete Revelation of Him [i.e. Augoeides].

Latin Intra Nobis Regnum deI literally means “Inside Us the Kingdom of god”.

Leopold Bloom, the nominally Catholic, ethnically Jewish protagonist of James Joyce’s Ulysses, remembers his wife Molly Bloom interpreting INRI as “Iron Nails Ran In”.[23][24][25][26] The same meaning is given by a character in Ed McBain’s 1975 novel Doors.[27] Most Ulysses translations preserve “INRI” and make a new misinterpretation, such as the French Il Nous Refait Innocents “he makes us innocent again”.[28]

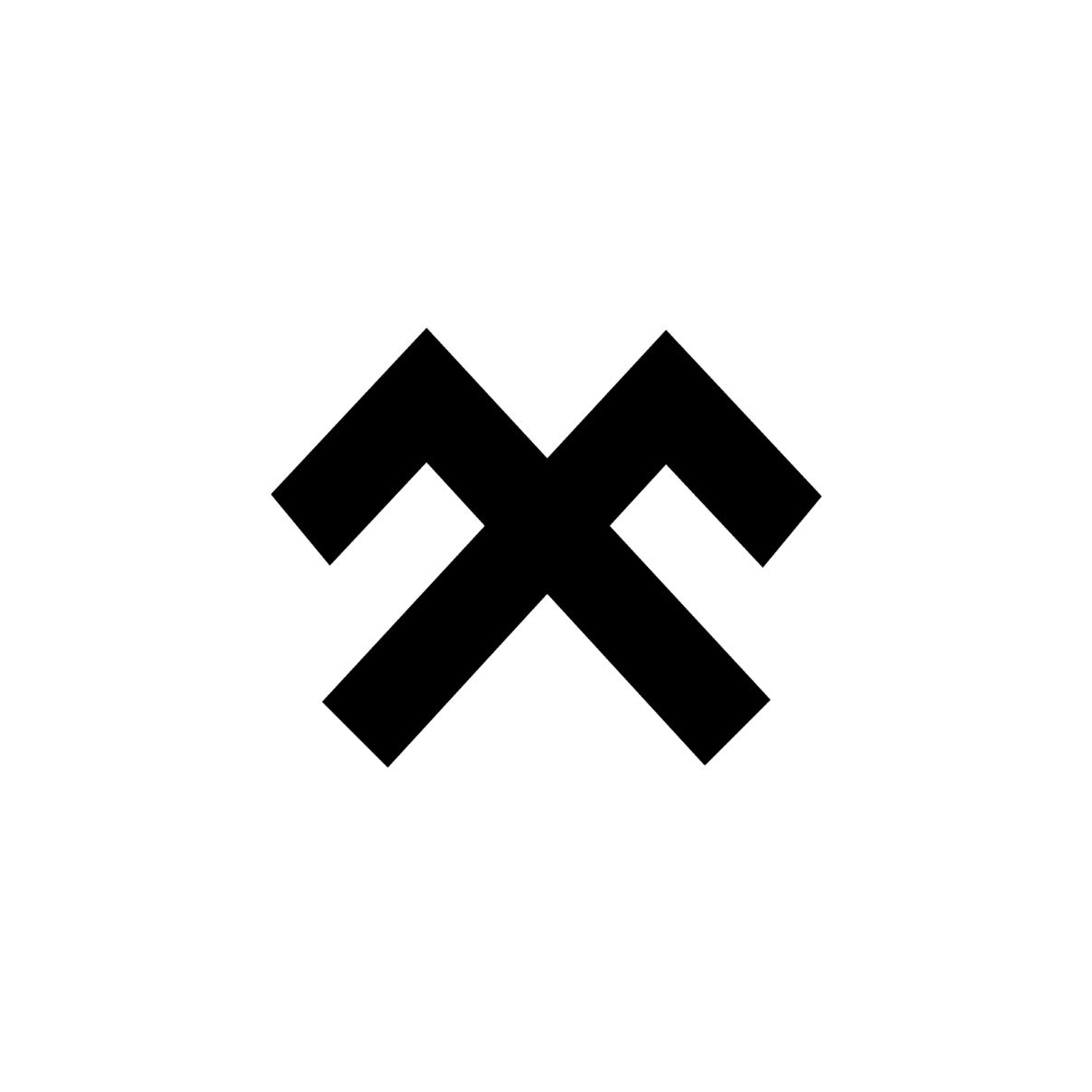

INRI has also been used as a magical formula in the occult, representing the passing of life to death and Resurrection. It has been used in many rituals including the Rose Cross and the Lesser Ritual of the Hexagram by both O.T.O, A∴A∴, and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.[29]

In isopsephy, a practice of adding up the number values of the letters in a word to form a single number, the Greek term (βασιλεὺς τῶν Ἰουδαίων) receives a value of 3343 whose digits seem to correspond to a suggested date for the crucifixion of Jesus, (33, April, 3rd day).

Conclusion

“INRI” is an abbreviation for the Latin “Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum” (“Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews”), posted on the cross by order of the Roman procurator, Pontius Pilate.

Besides the use in religious iconography and architecture, this initialism also appears in secret societies and the occult, as a magical formula.

[1] Boxall, Ian (2007). SCM studyguide to the books of the New Testament. p. 125. London: SCM Press. ISBN 978-0-334-04047-7. OCLC 171110263.

[2]France, R. T. (2007). The Gospel of Matthew. p. 1048. Grand Rapids, Mich: William B. Eerdmans Pub. ISBN 978-0-8028-2501-8. OCLC 122701585.

[3] Hengel, Martin (2004). Studies in Early Christology. p. 46. A&C Black. ISBN 0-567-04280-4.

[4] Luke 22:67, 23:1, and others

[5] See range of translations assembled at BibleGateway.com

[6] Robbins, V.K. (1996). Exploring the Texture of Texts: A Guide to Socio-Rhetorical Interpretations. pp. 76–77. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-56338-183-6.

[7] France 2007, pp. 43 and 83.

[8] Brown, R.E. (1994). Introduction to the New Testament Christology. pp. 78–79. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-8264-7190-1.

[9] Binz, Stephen (2004). The names of Jesus. pp. 81–82. Mystic, CT: Twenty-Third Publications. ISBN 1-58595-315-6. OCLC 56392998.

[10] Ironside, H.A. (2006). John. p. 454. Ironside Expository Commentaries Series. Kregel Publications. ISBN 978-0-8254-9619-6.

[11] Brown 1988, p. 93.

[12] Senior, Donald (1985). The Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew. p. 124. Vol. 1. M. Glazier. ISBN 0-89453-460-2.

[13] Hengel 2004, p. 46.

[14] De Bles, A. (1925). How to Distinguish the Saints in Art by Their Costumes, Symbols, and Attributes. p. 32. New York: Art Culture Publications. ISBN 978-0-8103-4125-8.

[15] Some translations render Ἑβραϊστί (Hebraisti), the Koine Greek word used in John 19:20, as "Aramaic" rather than "Hebrew". (Aramaic, which was closely related to Hebrew, had become a common vernacular of the Jews by this period. Hebrew was in decline, but would continue to be spoken in the region until the beginning of the 3rd century CE.) However, Ἑβραϊστί is consistently used in Koine Greek at this time to mean Hebrew and Συριστί (Syristi) is used to mean Aramaic. Other than the word itself, there is no direct evidence in the verse as to whether Hebrew or Aramaic is meant and translations of the verse which render Ἑβραϊστί as Aramaic are reliant on assumptions made outside of the text to justify it, rather than the text itself.

[16] Andreopoulos, A. (2005). Metamorphosis: The Transfiguration in Byzantine Theology and Iconography. p. 26. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-295-6.

[17] Lanciani, R.A. (1902). Storia degli scavi di Roma e notizie intorno le collezioni romane di antichità (in Italian). Vol. I. p. 89. E. Loescher.

[18] Weiss, R. (1969). The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity. p. 102. History e-book project. Humanities Press. ISBN 978-80-13-01950-9.

[19] Andreopoulos 2005, p. 26.

[20] Aslanoff, Catherine (2005). The Incarnate God: The Feasts of Jesus Christ. p. 124. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 0-88141-130-2.

[21] de Schio, Marcello Reghellini (1825). Esprit du dogme de la Franche-Maçonnerie (in French). p. 12. Brussels: H. Tarlier.

[22] Crowley, Aleister (March 1909). "The Temple of Solomon the King". The Equinox. 1 (1). London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent: 160.

[23] Bloom, Harold (1989). Middle twentieth century. The Art of the Critic. Vol. 9. p. 335. Chelsea House. ISBN 978-0-87754-502-6.

[24] Ellmann, Maud (2010). The Nets of Modernism: Henry James, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Sigmund Freud. p. 164. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49338-3.

[25] Quigley, Megan (2015). Modernist Fiction and Vagueness: Philosophy, Form, and Language. p. 128. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-19566-6.

[26] Mihálycsa, Erika (2017). "'Weighing the point': A Few Points on the Writing of Finitude in Ulysses". p. 61. Reading Joycean Temporalities. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-34251-4.

[27] McBain, Ed (2017). "Part Two". p. 65. Doors. Head of Zeus. ISBN 978-1-78854-045-2.

[28] Szczerbowski, Tadeusz (1998). "Language Games in Translation: Etymological Reinterpretation of Hierograms". In Strässler, Jürg (ed.). Tendenzen Europäischer Linguistik: Akten des 31. Linguistischen Kolloquiums, Bern 1996. Linguistiche Arbeiten. Vol. 381. p. 221. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110913767. ISSN 0344-6727.

[29] Regardie, Israel (1971). The Golden Dawn: The Original Account of the Teachings, Rites and Ceremonies of the Hermetic Order of The Golden Dawn. v. III, p. 308. Llewellyn Worldwide. ISBN 0-87542-664-6.

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.