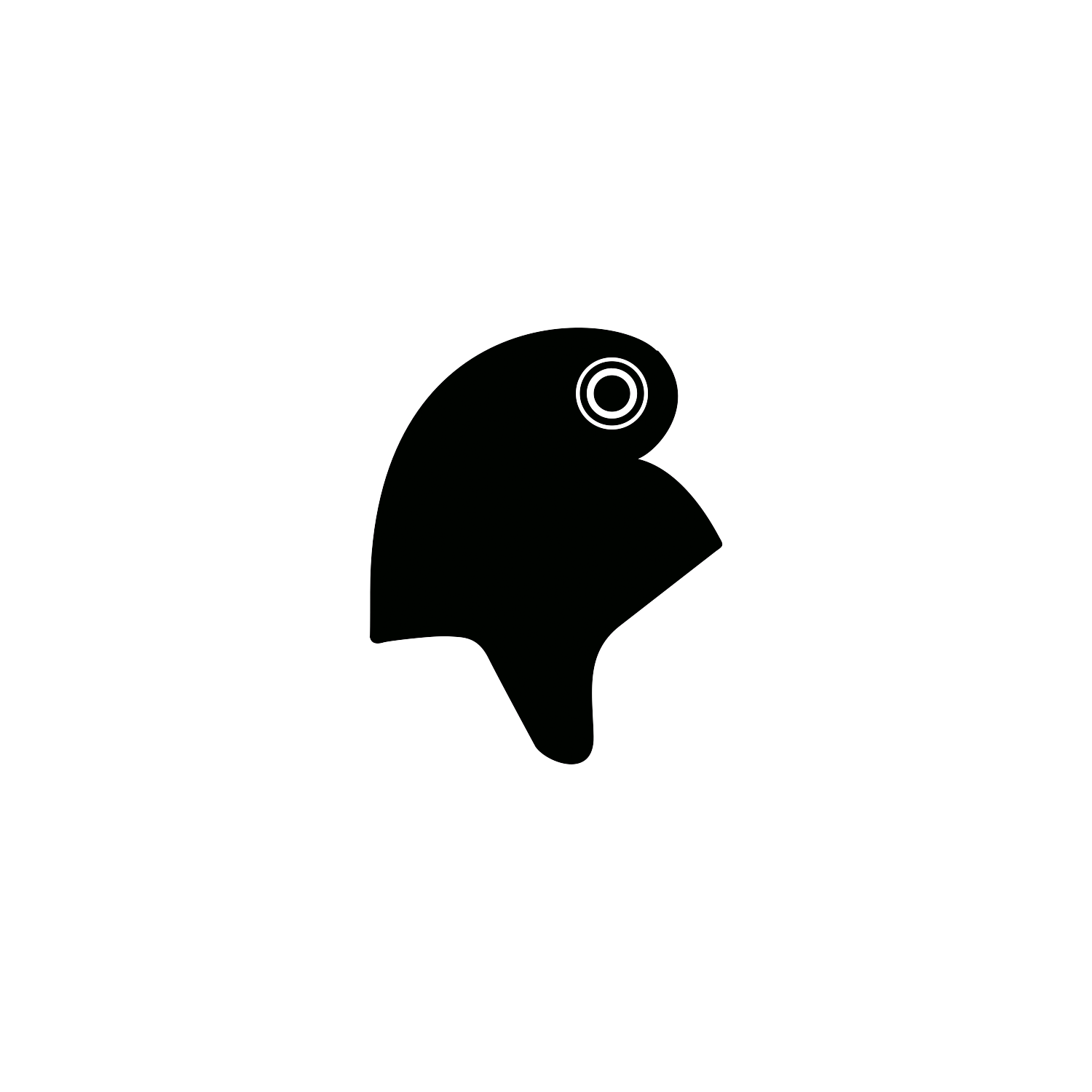

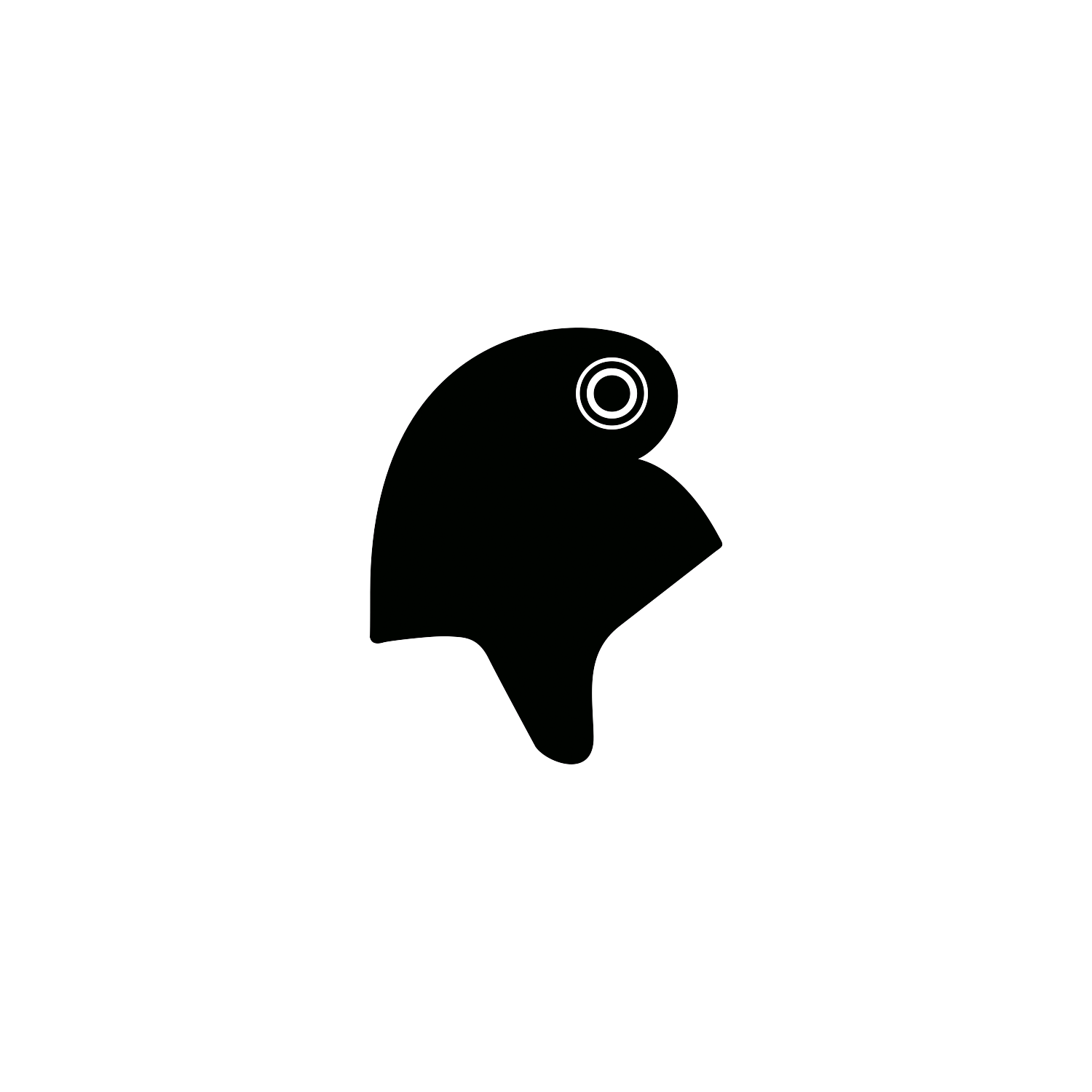

Phrygian Cap

Phrygian Cap

Also referred to as Liberty Cap.

Overview

The Phrygian cap (/ˈfrɪdʒ(iː)ən/ FRIJ-(ee)-ən) or liberty cap is a soft conical cap with the apex bent over, associated in antiquity with several peoples in Eastern Europe and Anatolia, including the Persians, the Medes and the Scythians, as well as in the Balkans, Dacia, Thrace and in Phrygia, where the name originated.[1]

Red Phrygian or ‘liberty’ caps were long associated with the theme of liberty in European and colonial cultures.

They were used as icons during the American Revolution and worn during the French Revolution in the late 1700s and came to symbolise allegiance to the republican cause. Along with the red, white and blue cockade, pinned to these and other hats, they became a lasting symbol of revolutionary France.[2]

The red, white and blue cockade also served as a revolutionary symbol in France. It was worn by thousands of ordinary people – often pinned to a liberty cap. Napoleon wore one of these cockades pinned to his bicorn hat at the Battle of Waterloo, as an emblem of his ‘man of the people’ persona.

The French Tricolore flag we know today was created during the French Revolution, adapted from these cockades. Marianne, the national symbol of the French republic is still often depicted wearing a Phrygian ‘liberty’ cap.

Origin and Meaning

What came to be labelled as the Phrygian cap was originally used by several Iranian peoples, including the Scythians, the Medes, and the Persians. From the reports of the ancient Greeks, it appears that the Iranian variant also was a soft headdress and called a tiara.

The Greeks identified one variant with their eastern neighbors and labeled it the “Phrygian cap”, although it was actually worn by nearly all Iranian tribes, from the Cappadocians (Old Persian Katpatuka) in the west to the Sakas (OPers. Sakā) in the northeast. This and other variants can be observed in the reliefs at Persepolis.

All seem to have been made of soft material with long flaps over the ears and the neck, but the form of the top varies. The famous “upright (orthē) tiara” was worn by the king. Members of the Median upper class wore high, crested tiaras.[3]

By the 4th century BC (early Hellenistic period), the Phrygian cap was associated with Phrygian Attis, the consort of Cybele, the cult of which had by then become graecified.

At around the same time, the cap appears in depictions of the legendary king Midas and other Phrygians in Greek vase-paintings and sculpture.[4]

By extension, the Phrygian cap also came to be applied to several other non-Greek-speaking peoples (“barbarians” in the classical sense). Most notable of these extended senses of “Phrygian” were the Trojans and other western Anatolian peoples, who in Greek perception were synonymous with the Phrygians, and whose heroes Paris, Aeneas, and Ganymede were all regularly depicted with a Phrygian cap.

Other Greek earthenware of antiquity also depict Amazons and so-called “Scythian” archers with Phrygian caps. Although these are military depictions, the headgear is distinguished from “Phrygian helmets” by long ear flaps, and the figures are also identified as “barbarians” by their trousers.

Greek representations of Thracians also regularly appear with Phrygian caps, most notably Bendis, the Thracian goddess of the Moon and the hunt, and Orpheus, a legendary Thracian poet and musician.

While the Phrygian cap was of wool or soft leather, in pre-Hellenistic times the Greeks had already developed a military helmet that had a similarly characteristic flipped-over tip. These so-called “Phrygian helmets” (named in modern times after the cap) were usually of bronze and in prominent use in Thrace, Dacia, Magna Graecia, and the rest of the Hellenistic world from the 5th century BC up to Roman times.

Due to their superficial similarity, the cap and helmet are often difficult to distinguish in Greek art (especially in black-figure or red-figure earthenware) unless the headgear is identified as a soft flexible cap by long earflaps or a long neck flap.

The Greek concept passed to the Romans in its extended sense, and thus encompassed not only to Phrygians or Trojans (which the Romans also generally associated with the term “Phrygian”), but also the other near-neighbours of the Greeks.

On Trajan’s Column, which commemorated Trajan’s epic wars with the Dacians (101–102 and 105–106 AD), the Phrygian cap adorns the heads of Dacian warriors. The prisoner, accompanying Trajan in the monumental, three meter tall statue of Trajan in the ancient city of Laodicea, is wearing a Phrygian cap. Parthians appear with Phrygian caps in the 2nd-century Arch of Septimius Severus, which commemorates Roman victories over the Parthian Empire. Likewise with Phrygians caps, but for Gauls, appear in 2nd-century friezes built into the 4th-century Arch of Constantine.

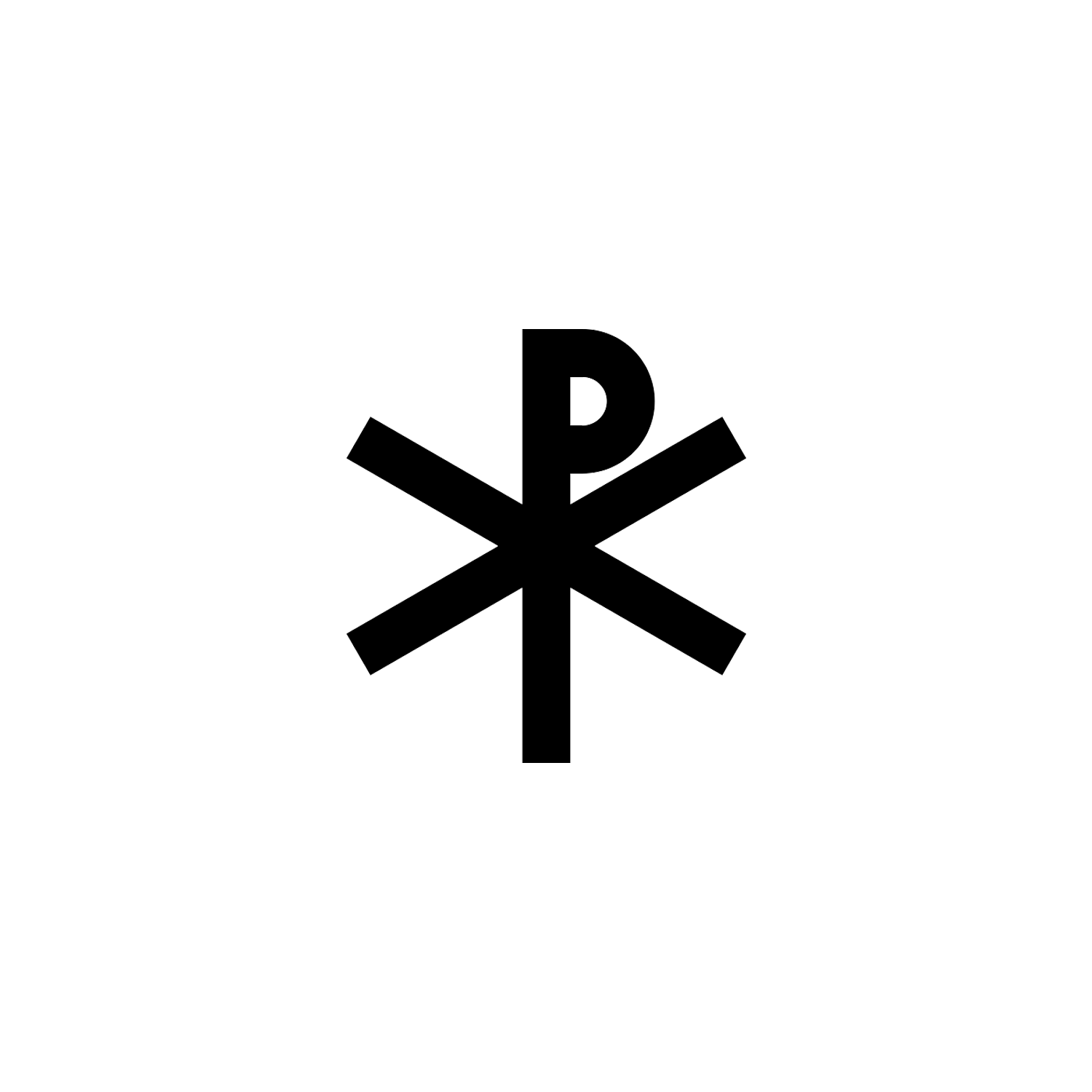

The Phrygian cap reappears in figures related to the first to fourth century religion of Mithraism. This astrology-centric Roman mystery cult (cultus) projected itself with pseudo-Oriental trappings (known as perserie in scholarship) in order to distinguish itself from both traditional Roman religion and from the other mystery cults. In the artwork of the cult (e.g. in the so-called “tauroctony” cult images), the figures of the god Mithras as well as those of his helpers Cautes and Cautopates are routinely depicted with a Phrygian cap. The function of the Phrygian cap in the cult are unknown, but it is conventionally identified as an accessory of its perserie.

Early Christian art (and continuing well into the Middle Ages) build on the same Greco-Roman perceptions of (Pseudo-)Zoroaster and his “Magi” as experts in the arts of astrology and magic, and routinely depict the “three wise men” (that follow a star) with Phrygian caps.

A symbol of Liberty

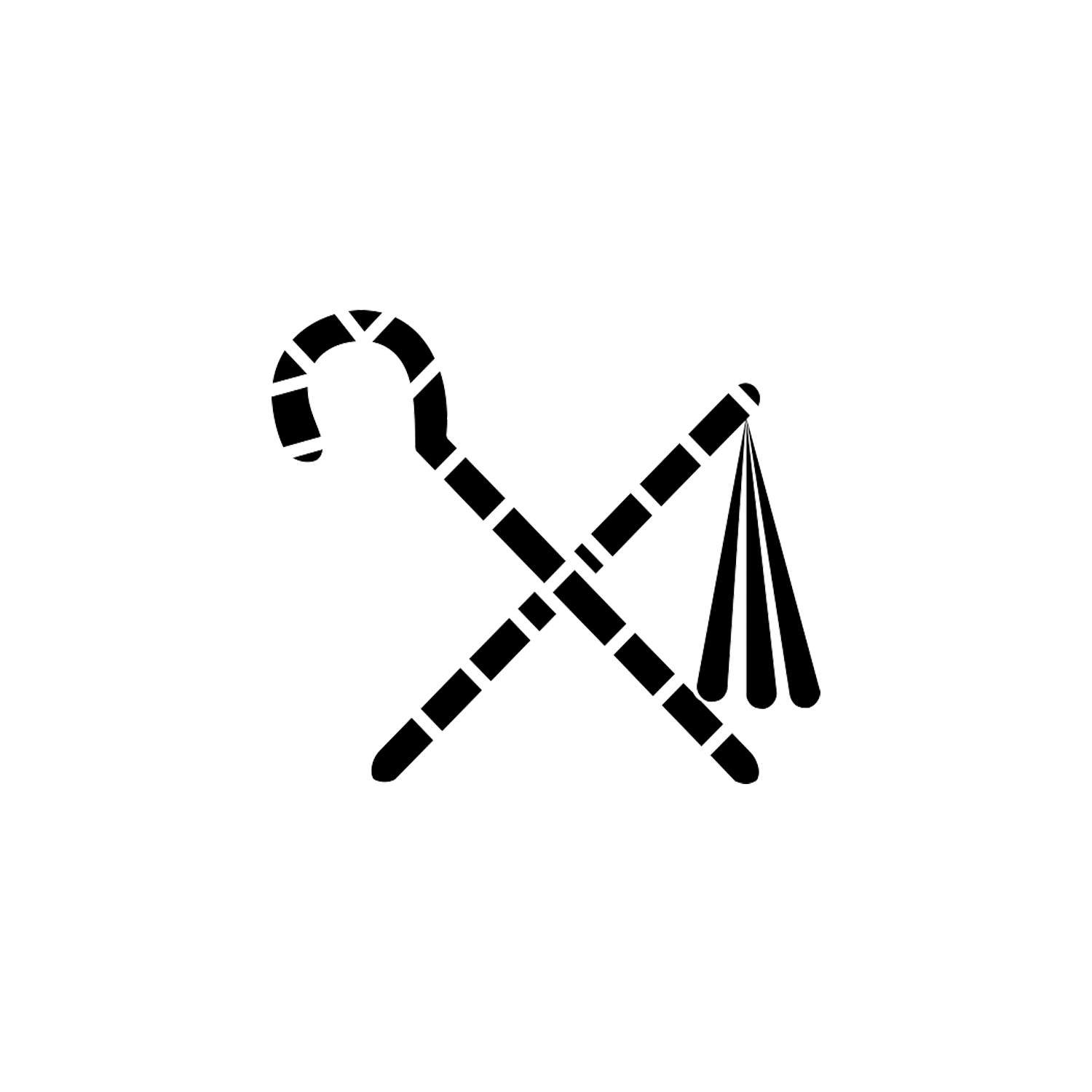

In late Republican Rome, a soft felt cap called the pileus served as a symbol of freemen (i.e. non-slaves) and was symbolically given to slaves upon manumission, thereby granting them not only their personal liberty, but also libertas – freedom as citizens, with the right to vote (if male). Following the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, Brutus and his co-conspirators instrumentalized this symbolism of the pileus to signify the end of Caesar’s dictatorship and a return to the (Roman) republican system.[5]

These Roman associations of the pileus with liberty and republicanism were carried forward to the 18th century, until when the pileus was confused with the Phrygian cap, then becoming a symbol of those values in the wake of Medieval Italian uses of the Phrygian cap, most notably in Venice.[6]

In Venice, the Phrygian cap was used by the Doge instead of a crown as a symbol of Republican liberty, from the Middle Ages until 1797. The symbol of Libertas as a female figure holding the Phrygian cap upon a spear appeared in the 1500’s in the Apotheosis of Venice, a major painting by Paolo Veronese in the Ducal palace, iconography that would later be reused in French and American art and coinage.

The use of a Phrygian-style cap as a symbol of revolutionary France is first documented in May 1790, at a festival in Troyes adorning a statue representing the nation, and at Lyon, on a lance carried by the goddess Libertas.[7] To this day the national allegory of France, Marianne, is shown wearing a red Phrygian cap.[8]

By wearing the bonnet rouge and sans-culottes (“without silk breeches”), the Parisian working class made their revolutionary ardor and plebeian solidarity immediately recognizable. By mid-1791, these mocking fashion statements included the bonnet rouge as Parisian hairstyle, proclaimed by the Marquis de Villette (12 July 1791) as “the civic crown of the free man and French regeneration.”

On 15 July 1792, seeking to suppress the frivolity, François Christophe Kellermann, 1st Duc de Valmy, published an essay in which the Duke sought to establish the bonnet rouge as a sacred symbol that could only be worn by those with merit. The symbolic hairstyle became a rallying point and a way to mock the elaborate wigs of the aristocrats and the red caps of the bishops. On 6 November 1793, the Paris city council declared it the official hairstyle of all its members.

The bonnet rouge on a spear was proposed as a component of the national seal on 22 September 1792 during the third session of the National Convention. Following a suggestion by Gaan Coulon, the Convention decreed that convicts would not be permitted to wear the red cap, as it was consecrated as the badge of citizenship and freedom. In 1792, when Louis XVI was induced to sign a constitution, popular prints of the king were doctored to show him wearing the bonnet rouge.[9] The bust of Voltaire was crowned with the red bonnet of liberty after a performance of his Brutus at the Comédie-Française in March 1792.

During the period of the Reign of Terror (September 1793 – July 1794), the cap was adopted defensively even by those who might be denounced as moderates or aristocrats and were especially keen to advertise their adherence to the new regime. The spire of Strasbourg Cathedral was crowned with a bonnet rouge in order to prevent it from being torn down in 1794.

In 1814, the Acte de déchéance de l’Empereur decision formally deposed the Bonapartes and restored the Bourbon regime, who in turn proscribed the bonnet rouge, La Marseillaise and Bastille Day celebrations. The symbols reappeared briefly in March–July 1815 during “Napoleon’s Hundred Days”, but were immediately suppressed again following the second restoration of Louis XVIII on 8 July 1815.

The symbols resurfaced again during the July Revolution of 1830, after which they were reinstated by the liberal July Monarchy of Louis Philippe I, and the revolutionary symbols—anthem, holiday, and bonnet rouge—became “constituent parts of a national heritage consecrated by the state and embraced by the public.”[9]

In Revolutionary America

In the years just prior to the Revolutionary War, Americans copied or emulated some of those prints in an attempt to visually defend their “rights as Englishmen”.[10] Later, the symbol of republicanism and anti-monarchical sentiment appeared in the United States as the headgear of Columbia,[11] who in turn was visualized as a goddess-like female national personification of the United States and of Liberty herself.

The cap reappears in association with Columbia in the early years of the republic, for example, on the obverse of the 1785 Immune Columbia pattern coin, which shows the goddess with a helmet seated on a globe holding in a right hand a furled U.S. flag topped by the liberty cap.[11]

Starting in 1793, U.S. coinage frequently showed Columbia/Liberty wearing the cap. The anti-federalist movement likewise instrumentalized the figure, as in a cartoon from 1796 in which Columbia is overwhelmed by a huge American eagle holding a Liberty Pole under its wings.[12] The cap’s last appearance on circulating coinage was the Walking Liberty Half Dollar, which was minted through 1947 (and reused on the current bullion American Silver Eagle).

The U.S. Army has, since 1778, used a “War Office Seal” in which the motto “This We’ll Defend” is displayed directly over a Phrygian cap on an upturned sword.

In 1854, when sculptor Thomas Crawford was preparing models for sculpture for the United States Capitol, then-Secretary of War Jefferson Davis insisted that a Phrygian cap not be included on a Statue of Freedom, on the grounds that “American liberty is original and not the liberty of the freed slave”. The cap was not included in the final bronze version that is now in the building.[13]

Modern depictions

The Phrigian cap appears on the state flags of West Virginia and Idaho[14] (as part of their official seals), New Jersey, and New York, as well as the official seal of the United States Senate, the state of Iowa, the state of North Carolina (as well as the arms of its Senate,[15]) and on the reverse side of both the Seal of Pennsylvania and the Seal of Virginia.

In the Belgian comic franchise The Smurfs, the eponymous Smurfs are typically depicted wearing Phrygian-like caps.[16]

Announced in November 2022, the official mascots of Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games, named The Phryges, were based on the cap.[17]

Conclusion

In antiquity this conical headgear was worn by the inhabitants of Anatolia, including the Trojans and the Phrygians (who gave it its name). During Roman times the pileus, a more rounded hat, was worn by former slaves who had been freed.

During the French revolution the Phrygian cap came to symbolise newfound liberty based on laws and constitutions. Although the Phrygian cap had never really featured in the traditional attire of the French people, Parisian artisans and workers living in the Faubourg Saint-Antoin used to wear bonnets (caps) which had a similar shape.

From 1792 onwards, the red woollen cap was worn in support of the revolutionary government. Such bonnets de la liberté (liberty cap) became ubiquitous in the prints, paintings, and cartoons of the period, both at home and abroad.

The political message of the liberty cap did not fade away. Today the liberty cap stands in numerous coat of arms, state seals and flags, coins and even popular culture.

[1] "Phrygian cap | Definition, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica.

[2] Richard Wrigley, "Transformations of a revolutionary emblem: The Liberty Cap in the French Revolution, French History 11(2) 1997, p. 132.

[3] Calmeyer, Peter (15 December 1993). "CROWN i. In the Median and Achaemenid periods". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

[4] Lynn E. Roller, "The Legend of Midas", Classical Antiquity, 2.2 (October 1983:299–313) p. 305.

[5] Cf. Appian, Civil Wars 2:119: "The murderers wished to make a speech in the Senate, but as nobody remained there they wrapped their togas around their left arms to serve as shields, and, with swords still reeking with blood, ran, crying out that they had slain a king and tyrant. One of them bore a cap on the end of a spear as a symbol of freedom, and exhorted the people to restore the government of their fathers and recall the memory of the elder Brutus and of those who took the oath together against ancient kings."

[6] Korshak, Yvonne (1987), "The Liberty Cap as a Revolutionary Symbol in America and France", Smithsonian Studies in American Art, 1 (2): 52–69, doi:10.1086/424051.

[7] Albert Mathiez, Les Origines des cultures révolutionnaires, 1789–1792 (Paris 1904:34).

[8] Richard Wrigley, "Transformations of a revolutionary emblem: The Liberty Cap in the French Revolution, French History 11(2) 1997:131–169.

[9] Philip G. Nord (1995). The Republican Moment: Struggles for Democracy in Nineteenth-Century France. President & Fellows of Harvard College.

[10] Zeiler, Frank (2014). Visuelle Rechtsverteidigung im Nordamerikakonflikt. Ein Beitrag zur Rezeption der englischen Freiheits- und Verfassungssymbolik in nordamerikanischen Druckgraphiken der Jahre 1765–1783, Signa Ivris, Vol. 13 (2014), pp. 315-346 (in German). Vol. 13. doi:10.6094/UNIFR/11157. ISBN 9783941226326.

[11] McClung Fleming, E. (1968), "Symbols of the United States: From Indian Queen to Uncle Sam", Frontiers of American Culture, Purdue Research Foundation, pp. 1–25, at pp. 12, 15–16.

[12] McClung Fleming, E. (1968), "Symbols of the United States: From Indian Queen to Uncle Sam", Frontiers of American Culture, Purdue Research Foundation, pp. 1–25, at pp. 12, 15–16.

[13] Gale, Robert L. (1964), Thomas Crawford: American Sculptor, University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, p. 124.

[14] "Seal of Idaho". State Symbols USA. 12 September 2014.

[15] "Senate of North Carolina", College of Arms Newsletter, No. 8 (March 2006), London: College of Arms

[16] Tzvetkova, Juliana (12 October 2017). Pop Culture in Europe. ABC-CLIO. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4408-4466-9.

[17] "Meet Olympic Phryge and Paralympic Phryge: The story of the Paris 2024 mascots". 14 November 2022.

Latest Symbols

Monthly Digest

A summary of symbols for the month in a quick read format straight to your inbox.